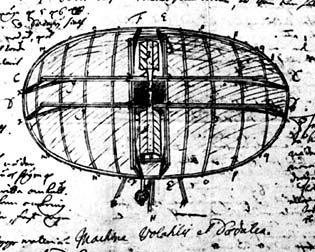

We think of hovercraft as a modern conveyance. After all, any vision of the future usually includes hovercraft or flying cars along with all the other things we imagine in the future. So when do you think the hovercraft first appeared? The 1960s? The 1950s? Maybe it was a World War II development from the 1940s? Turns out, a human-powered hovercraft was dreamed up (but not built) in 1716 by [Emanuel Swedenborg]. You can see a sketch from his notebook below. OK, that’s not fair, though. Imagining it and building one are two different things.

[Swedenborg] realized a human couldn’t keep up the work to put his craft on an air cushion for any length of time. Throughout the 1800s, though, engineers kept thinking about the problem. Around 1870, [Sir John Thornycroft] built several test models of ship’s hulls that could trap air to reduce drag — an idea called air lubrication, that had been kicked around since 1865. However, with no practical internal combustion engine to power it, [Thornycroft’s] patents didn’t come to much. In America, around 1876 [John Ward] proposed a lightweight platform using rotary fans for lift but used wheels to get forward motion. Others built on the idea, but they still lacked the engines to make it completely practical.

But even 1940 is way too late for a working hovercraft. [Dagobert Müller] managed that in 1915. With five engines, the craft was like a wing that generated lift in motion. It was a warship with weapons and a top speed of around 32 knots, although it never saw actual combat. Because of its physical limitations it could only operate over water, unlike more modern craft.

It would be 1926 or so before [Konstantin Tsiolkovskii] worked out the mathematics of the hovercraft. Meanwhile, in 1929, Ford (the car company) was experimenting with pressurized air floating things like factory equipment and trains. This wasn’t practical for building a hovercraft, though.

It was a Finn, [Toivo Kaario] that worked out the practical aspects of using a flexible envelope for lift. He failed to get funding, but did inspire [Vladimir Levkov] who built several fast attack boats similar to the [Müller] design. Some of these could reach 70 knots. Paradoxically, the war ended his efforts. An American, [Charles Fletcher] developed the Glidemobile (see below) during the war, but the project was classified at the time.

Post War

A British engineer, [Christopher Cockerell] and his team worked out the methods of modern hovercraft — apparently through experiments with a coffee tin, a cat food tin, and a hairdryer. Using a curtain with trapped air inside allowed a smaller airflow to have a much larger impact than in previous designs. At first, the military classified it. However, the air force didn’t want a boat and the navy didn’t want an airplane, so by 1958, [Cockerell] was free to pursue commercial development. As an aside, [Cockerell] was part of the teams that developed the first radio direction finder and radar.

By 1962, there was commercial ferry service on a small scale and by 1968, there was serious commercial use, with a ferry carrying up to 254 passengers and 30 cars. Today, Hovertravel still offers public service between the Isle of Wight and England (see below).

Not That Modern After All

Who knew that a vehicle that we still think of as futuristic has roots going back 300 years? Even if you discount the early work, real hovercraft were operational well before World War II. They still have their uses although passenger service has declined. A combination of tunnels, more efficient multi-hull boats, and reduced surface travel have conspired to make hovercraft ferries an oddity.

The famous ferry between Calais and Dover was a noisy beast, as you can see in the 1991 video, below. The noise is one reason that there was rarely any use of hovercraft on rivers through major cities.

If you want to dip your toe into this old but new tech, we looked at a 3D printed hovercraft recently. Here’s another one that might feed your need for speed. Oh. And before you ask “Where’s the hack?” We’d ask you to consider this:

Artwork Source: “The Windmiller’s Guest” by Edmund Blair Leighton with added awesomeness from Joe Kim

I know I’ve seen them up close, and I almost have a feeling I’ve been on one when a kid, but I don’t have concrete memories.

I was on a hydrofoil once, I think in Denmark about 1965, and it seemed exotic at age five, but in retrospect isn’t as neat as a hovercraft.

Michael

Here, hydrofoil ships are mostly tourist attraction (Russia), and as far as I know – that series is no longer produced. But they are cool looking (https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9C%D0%B5%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BE%D1%80_(%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BF%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%85%D0%BE%D0%B4)

Look up hydrofoil ferrys, those are cool, rise about 20ft out of water

my hovercraft is full of eels

+100

Do you waaaaantttttt…..

Actually, I’m a Gynaecologist – but this is my lunch hour.

I can’t believe nobody has said it yet; that art is incredible! Well done Joe Kim.

Man, yeah. I always look forward to seeing what he does with these pieces.

Lately I’ve been imagining a train of hover-barges dragged by a snowplow/grooming machine. The lead barge would have copious diesel and a genset and all barges would have electric fans inflating the skirt. I envision a large quantity of goods could be moved over soft/wet terrain – such as marsh lands/muskeg/partially frozen winter roads, etc.

An unfortunate situation is playing out in northern Manitoba where a damaged American owned (leased?) rail line to a remote community is not being repaired and it’s causing grief for the residents who depend on the rail to get heavy goods in. A make shift winter “road” has been created (something certainly worthy of a HAD article on its own). But due to muskeg, etc it’s unlikely to support heavy hauling trucks.

I keep thinking – why not hovercraft based barges…

Terrain level enough? And we (US) have ONE sound heavy ice breaker… and IT is stuck.

I think it’s flatter than Saskatchewan up there….

Hovercraft is not a very steerable vehicle, and it will not brake for anyone. Your idea could work on an open tundra (and would really excell during summer when it thaws into a marsh), but not in an mountain range or a woodland.

Dunno why you think that. Had several rides on the USN’s LCAC out of their ACU based on Camp Pendleton. With a ‘big’ load (two AAVs and one hummer and other stuff) at 50 to 60 knots, they pivoted and changed direction in less than 3 radii of the craft (lateral gs knocked me down). When we reached San Clemente, the pilot had to maneuver through several LCUs docked in the cove by going sideways and pivoting in place. Hovercraft are magnificent beasts.

While they are not supposed to traverse rough terrain, they do reduce speed and time over land to reduce damage to the skirt. But they can easily travel over flat land.

” a damaged American owned (leased?) rail line to a remote community is not being repaired ”

Interesting, Canadian Pacific (CP Rail) has bought up a lot of US railroads in the northern lower 48 the past few years. Some of these lines were on the verge of abandonment. They are making good use of them, probably because they can ship goods south to open waters as opposed to waiting for Churchill, MB to thaw.

Soviets had this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tupolev_A-3_Aerosledge ;-)

Too heavy. You would be better off with building a large hovercraft like the one that was used as a channel ferry. Think of it this way the lift fans use energy by the hour not by the mile. Going fast will save fuel as far as the lift fans go. Also why a diesel when you could use gas turbines? Diesels are heavy so that will decrease your cargo load. Also no need to have generators and electric motors. Those are just more weight.

A large hovercraft made with advanced composites and modern gas turbine engines might be a solution. You would have to workout the cost of production, the cost of fuel, the max payload and the trade off of speed vs lift fan fuel use, and safety. You could potentially use low aspect ratio wings and “fly” at least in part in the ground effect to reduce the lift fan fuel use.

Or just fix the rail line which would probably be the cheapest and best solution.

sounds like you’re thinking along the lines of the old Letourneau Overland Trains, but throwing hovercraft tech in there. lay down some Marston Mat in the squishier spots, and stick with wheels. big ones. I can see a crosswind really laying havoc on a train of hover barges.

or if the rail company relinquishes it’s rights to the tracks, start your own train. a few flatbeds and a decent truck, and adapt them to the rails.

of course, some government bureaucrat will come along and wag their finger at you. a lot of innovation stops at the finger-wagging unfortunately.

I’m a bit confused by the title – isn’t this article about the hovercraft of the past?

Huh, I see your point. I think I was going for “we think of hovercraft as futuristic but it is older than you think.” Oh well, still better than “Hovercraft use this one weird trick to float over water.” Or… “Texas residents are shocked at these hovercraft.”

“Cars hate him!”

They could have made an impact at D-day. 30 foot tides at a smooth beach.

FYI, the US Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force currently use hovercraft for amphibious landings: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landing_Craft_Air_Cushion.

My hovercraft is full of eels. http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-BM02yP4kUOg/VqPg_YtihuI/AAAAAAAAcgg/jFk0UL6D7K8/s320/My%2BHovercraft%2BIs%2BFull%2Bof%2BEels.jpg

Does the US military have any surplus LCACs they’d sell cheap?

For those interested in these fascinating machines, there is a 700 page book with 450 pictures called ‘On a Cushion of Air’, (available through Amazon and Kindle), which tells the story of Cockerell’s discovery (1953) that heavy weights could be supported by low pressure air and the development of the hovercraft from the early days to the heyday of the giant 165-ton SRN.4, which crossed the English Channel starting in 1968 carrying 30 cars and 254 passengers at speeds in excess of 75 knots. The SRN.4 was widened and lengthened to an AUW of 320 tons and could carry 54 cars and 424 passengers (3rd picture down) for only a minimal increase power, proving conclusively that Cockerell’s theory was sound. The service ended on 1st October 2000 for economic reasons. Six SR.4s were built. The book also covers the development of military hovercraft and the only remaining commercial service in the world (2nd picture down). Hovertravel, from Southsea to Ryde, England.

As a touristy thing I took the hovercraft from Dover(?) to Calais(?) and later the ferry back.

I felt like my teeth were going to get shaken out on the hovercraft. The ferry was like riding an apartment. No sense of movement at all. It took a little longer to take the ferry but the connections were easier to make.

My memory of the hovercraft is:

– this is ana amazing futuristic thing

– the inside of a sick bag

Skirt dedign nevrr progressed, as poly tires went radial. It is a limitation. Never tried a foiled boat. Comment of comparison, ridewise?

Nice article, but we caulkheads (from the Isle of Wight) are also from England! We aren’t separate like the Isle of Man. “Hampshire, England” would be factually correct.

Broke your Tiny Whoop? Convert it to a Tiny Whoov – a super small FPV hovercraft. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z1WTOKDZ8gM

How about a flying hovercraft…

https://www.hammacher.com/Product/11933