It is fair to say that many technologies have been influenced by human vices. What you may not realize is that vending machines saw their dawn in this way, the first vending machine was created to serve booze. Specifically, it was created to serve gin, the tipple of choice of the early 18th century. it was created as a hack to get around a law that made it harder to sell alcoholic drinks. It was the first ever vending machine: the Puss and Mew.

England in the early 18th century was a drunken place. Because there were few reliable safe sources of water, pretty much everyone drank alcoholic drinks — too much might make you sick but not in the way that tends to kill you. Even children drank Small Beer, the weakest batch made at the end of the brewing process.

However, some parts of society at the time were concerned about the rise in popularity of hard spirits such as gin. Groups like the Society for the Reformation of Manners preached that hard liquor was destroying the lives of the working class. To restrict the sale of gin, the Gin Act was passed by parliament in the United Kingdom in 1736. This required that anyone selling small amounts of gin needed a license, which cost £50 (over£7,000/$9,000 in today’s value). Paid informers were enlisted to catch those who broke the law. They would buy illegal gin, report it to the police, and pocket the fine that the seller paid.

Hacking Liquor Laws

To get around this, an enterprising gin slinger by the name of Captain Dudley Bradstreet came up with a hack to sell gin: the Puss and Mew, also known as Bradstreet’s Cat.

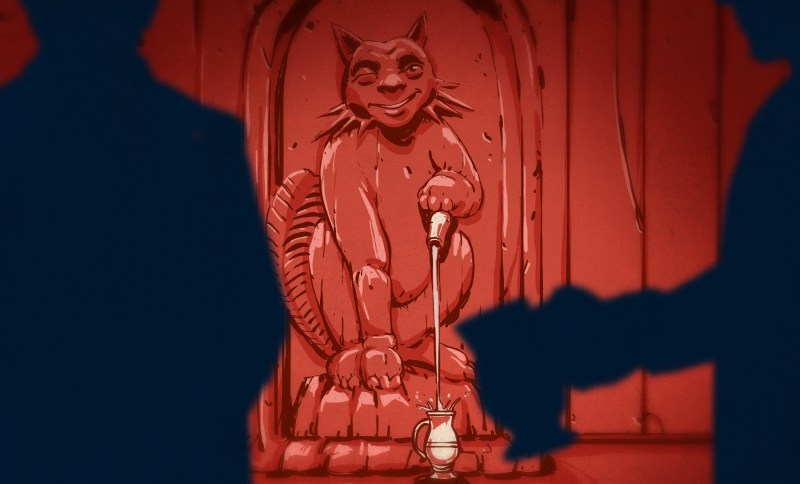

Bradstreet was a soldier and spy who had fallen on hard times. He carefully read the Gin Act, and realized that it did not give the police the authority to enter a building. Instead, they had to rely on informers to catch a gin seller. So, he persuaded a lawyer friend to rent a house and mounted a statue of a cat on an outside wall. A would-be drinker would walk up to the statue and ask ”Puss, do you have any gin?” The statue would meow, and a small drawer would open in its mouth. The drinker would insert coins and the drawer would close. Next, gin would flow out of a pipe in the cat’s paw.

It worked not because of a mechanism, but because Bradstreet was behind the cat, taking the money and pouring the gin down the pipe. Because he was hidden inside the house, an informer could not tell the police who had sold them the gin. And the police had no authority to enter the house and catch him, as the renter was a lawyer who refused to reveal the name of the occupant, claiming it was part of an ongoing court case.

It worked like a charm. As Bradstreet himself put it in his boastful memoir, The Life and Uncommon Adventures of Captain Dudley Bradstreet:

The Mob being very noisy and clamorous for want of their beloved Liquor…it soon occurred to me to venture upon that Trade. I bought the Act, and read it over several times, and found no Authority by it to break ones Doors, and that the Informer must know the Name of the Person who rented the house it was sold in. To evade this, I got an Acquaintance to take a House in Blue Anchor Alley…and purchased in Moorfields the Sign of a Cat, and had it nailed to a Street Window. I then caused a Leaden Pipe… to be placed under the Paw of the Cat…When the Liquor was properly disposed, I got a Person to inform a few of the Mob that Gin would be sold by the Cat at my Window the Next Day, provided they put money in its mouth… I heard the Chink of Money, and a comfortable voice say, “Puss, give me two Pennyworth of Gin.” I instantly put my mouth to the tube, and bid them receive it from the Pipe under her Paw…. from all parts of London People used to resort to me in such Numbers, that my neighbors could scarely get in or out of their Houses. After that manner I went on for a Month, in which time I cleared upwards of two and twenty Pounds

Like Mushrooms, Good Ideas Pop Up Everywhere

Bradstreet was the first to use this legal hack, but others quickly figured it out, and similar sellers were soon appearing all over London. Despite the Gin Act, the amount of gin consumed across London increased, and subsequent changes in the law made it easier to get a license to sell gin. By 1750, there were about 29 thousand licensed gin sellers across England, and more who were still selling illegally.

Although the Puss and Mew has little in common with modern vending machines, it is the first device of its kind. And it is worth noting that they came about because of the thirst of the working class of London for booze, and one mans inventive approach to retailing.

Bradstreet himself gave up the scheme once it was no longer profitable, and moved on to other schemes. In 1745, he became a government spy in the camp of the Jacobite rebellion and convinced them that a fake army was ahead. This persuaded the Scottish army to turn back before attacking Northampton, effectively ending the rebellion.

The original location of the Puss and Mew no longer exists: Blue Anchor Alley was destroyed in the 1960’s and replaced by a nasty-looking tower block. The original sign is also no longer around, but the Beefeater distillery in London does have a replica Puss and Mew that can be viewed on their tour. Alas, it no longer serves gin.

Hero of Alexandria had produced a coin-operated vending machine for holy water around 10AD, which is definitely earlier than this, but may not be the first vending machine.

Just thinking the same thing.

A Mechanical Turk of a vending machine!

Legal hack certainly. Not sure I’d call it a “device” in the traditional sense.

>”England in the early 18th century was a drunken place. Because there were few reliable safe sources of water, pretty much everyone drank alcoholic drinks”

Are you sure? People sure drank alcohol, but not to the extent and not around the countryside.

The English parliament promoted the distillation of surplus grain into gin to get more tax revenue from the sale of alcohol, which then saturated the markets at very low prices and had the unintended consequence that lots of people started boozing up. That became the Gin Epidemic. The epidemic was pretty much local to London, where a small minority of people drank 18 million gallons of gin a year.

From 1685 to 1733 the (known) production and consumption of gin had increased 10x. The parliament acted and added the prohibitions in 1736. The consumption dropped back to under 2 million gallons by 1758.

This sounds so incredibly british

By 1743, England was drinking 2.2 gallons of gin per person per year.

By 1830, (US) alcohol consumption reached its peak at a truly outlandish 7 gallons of ethanol (17.5 gallons of whisky) a year per capita.

That can’t be right. Are you sure that’s not in liters, because that’s almost a quart and a half per week for everybody, babies and grandmothers included.

Knowing that a good quarter of the population doesn’t drink, and at least another quarter won’t drink, that leaves so much drinking to be done for the remainder that they should have been dead!

I would believe in 17.5 liters of whisky per person per year, and that’s quite a lot as well.

> This sounds so incredibly british

What part? Government analyzing a situation and acting on it?

I wonder how many gallons I consumed in 2017

Estimate 1 gallon per week of 2017 that you don’t remember.

3.9 litre US gallons, or 4.5 litre British gallons?

Luke, never thought I would be discussing Gin consumption in London in the 18th century on Hackaday, but…

The Puss and Mew was in place right after the 1736 Gin Act, which was the first Gin Act. It was, thanks to the Puss and Mew and other ways around it, a complete failure. The sources I found suggested that the amount of Gin consumed increased after the 1736 act, rather than the decrease that the writers hoped for. One source claimed an average of 2.2 gallons of Gin per person, per year, which is a lot. I can’t find if that is for London or a wider average. Anyway, people were drinking a lot, some of it from sources like the Puss and Mew.

So, Parliament passed another Gin Act in 1751 that tightened the laws on the distillers, making it illegal to sell Gin in any quantity without a license, targetting the distillers. That was probably the main driver that lead to the 1758 figures you mention, as it made Gin more expensive and only available in licensed premises, such as the local pub.

Cheers,

Richard

Part of the reason why gin consumption went down is because beer became cheaper thanks to advanced brewing techniques born out of better understanding of biology.

The microscope had just been invented, and people started developing germ theory, which lead to better understanding of the fermentation process, isolation and development of yeast strains, industrial processes for brewing and cleaner, cheaper, stronger, more long lasting and even quality beer that the poor could afford.

>”One source claimed an average of 2.2 gallons of Gin per person, per year, which is a lot.”

It comes out to about 1.7 dl per person per week, which is like drinking 3-4 pints. That’s not much as an average consumption, but we have to remember that most likely about 20% of the drinkers drank 80% of the booze (Pareto principle) so some people were drinking the equivalent of 14 pints a week all through the year while others only had a small tipple on sundays.

Of course that’s on top of all the rest of the alcohol consumption.

3-4 pints made me think you were saying they were drinking 3-4 pints of gin a week and that was “not much”. It was AFTER writing my comment that I realized you were comparing the gin consumption to beer.

How strong was gin then anyway? Are we talking watered down to 20% or less ABV or up at the 57.5 “100 proof” standard or higher?

As the grain prices and taxes went up, they probably started watering it down.

Holy moley, that’s great! One thing is certain, the Puss & Mew definitely had character.

I really wish people would stop using the word “hack” like this. It’s not a legal hack… it’s a loophole. Same with “life hacks”… they’re not “hacks”… they’re tips.

What’s the definition of a hack in your book? I’d say it is something like “using something in a usually clever way for which it originally was not intended”, which seems to fit the bill.

“Hacking” outside of the computer context means doing something poorly and ad-hoc – just barely clearing the bar due to a lack of expertise or professionalism,or because you’re cheating somehow.

In my book, when not referring to the annoying but established media usage of “attacking IT infrastructure”, a hack is defined as “(typically a small) modification to a piece of hardware or software to get it to perform a job it was not originally intended to do”. This clearly does not include anything built for the purpose from scratch, “clever usages” of anything in their unchanged state, any usages of anything immaterial (like laws or rules) excepting customized computer code, any loopholes, any “life hacks” etc. But hey, that’s just me. And yeah, the Puss was a cool loophole exploit…

After reading HackADay these past ten years or so…

I think a lot of “good hacks” have come about because of “legal loopholes”!

Curious definition you’re using there.

This isn’t a hack, it’s an ad-hoc alteration of a piece of software.

This isn’t a hack, it’s a re-use of obsolete hardware in an unforeseen way.

This isn’t a hack, it’s an exploitation of a bug in the Windows kernel.

A screwdriver in a broken car ignition lock is a hack. A paperclip in a battery holder to use a spare AAA cell instead of AA is a hack. Everything that (old) McGuyver did pretty much counts as a hack. (The rebooted show is itself a hack).

Most of what’s on Hackaday doesn’t really count as a hack. There’s other terms for it: art, crafts, hobby electronics… just making or doing stuff nowadays gets called “hacking” for no good reason. You put the paperclip on a stack of papers, or string some macaroni to make christmas decorations, and it’s a “lifehack”.

“Hack,” n. A thing a person can do or make or say

By that definition, everything is a “hack” since pretty much everything falls within the parameters of “do, make or say”.

I’m agreeing with you that the usage of the word is too broad, silly.

It’s like “maker.” Everyone makes things, it’s quintessentially human. Just like everyone bends rules and tries to make the best they can out of limited resources. Is it a kludge, a hack, or just another Tuesday? Does any of this really mean anything, or are we just senselessly squirting different syllables through our monkey-face-holes?

But hey, it’s an interesting story after all. A bar somewhere should bring it back as an alternative way to order gin–from a creepy wooden cat that has a man’s face for some horrible reason.

lol… sorry. It’s hard to be sure through text :)

And yeah.. I found the story interesting, too.

A minor correction, but the Blue Anchor Alley you’ve linked to on Google Maps is in Richmond which would have been a good day’s travel from London at that time. The correct Blue Anchor Alley even survived the blitz, but has now vanished under 1960s redevelopment. It ran from the end of Errol St to Bunhill Row

Jim, thanks for the info: I will update the article with that nugget! A pity that the area no longer exists as such, but that’s 1960’s urban improvement for ya.

It was commonplace in Rome to have vending machines in bath houses that worked on the weight and size of a coin to dispense things like soap. This is far from the first bending machine even in wide use.

Neat, did not know that. First or not, I enjoyed the article.

I think in general people underestimate our ancestors.

so using a fake coin, of the correct weight, would have been a “hack” ?

Of course faking money is probably nearly as old as money itself. But it was and still is considered more of a crime and not a “hack”.