Of all the lessons that life hands us, one of the toughest is that you can be right about something but still come up holding the smelly end of the stick. Typically this is learned early in life, but far too many of us avoid this harsh truth well into adulthood. And in those cases where being right is literally a matter of life or death, it’s even more difficult to learn that lesson.

For Ignaz Semmelweis, a Hungarian physician-scientist in the mid-19th century, failure to learn that being right is attended by certain responsibilities had a very high cost. Ironically it would also save the lives of countless women with a revolutionary discovery that seems so simple today as to be self-obvious: that a doctor should wash his hands before seeing patients.

Anything But First Clinic

When Semmelweis was born in the Hungarian city of Buda in 1818, medicine was only just emerging from the accumulated misconceptions and malpractices of the Renaissance period and the Dark Ages before that. Bloodletting, although falling out of favor as the physician’s therapy of choice, was still practiced, despite the fact that the “four humours” that the procedure sought to balance had largely been abandoned as an explanation for health and disease in favor of “miasmas,” or bad air. Physicians were finally beginning to apply Enlightenment-age advances and scientific methods to the problem of diagnosing and treating disease – but only just barely.

Semmelweis, the son of a wealthy merchant, took a circuitous route to medicine through the study of law, but by 1846 he had won an appointment to the obstetrics ward of Vienna General Hospital. It was a less than prestigious posting, and not his first choice, but Semmelweis threw himself into the routine of a busy physician in an institution set up specifically to serve the impoverished classes of Viennese society, for whom infanticide seemed a reasonable method of birth control.

To stem this practice, the hospital offered free care to pregnant women, with the predictable effect of overwhelming the physicians of the obstetrics clinic. To deal with the overflow, a second obstetrics clinic was established, staffed entirely by midwives. The two clinics quickly developed opposite reputations among the people of Vienna. While Second Clinic was seen to be as safe as any place dealing with childbirth in the 19th century could be, First Clinic was widely known to be a death sentence: women who delivered there were as likely as not to die there.

As a staff member of First Clinic, Semmelweis was painfully aware of this reputation, and undertook a study of the problem. He found that while the statistics were not quite as bad as the word on the street had it, they were still appalling: fully 13% of women who delivered in the First Clinic died as a result of postpartum infection, whereas the Second Clinic rate for the same complication was a mere 2%. This seemed to fly in the face of the facts; after all, First Clinic was staffed by physicians, far more learned and skilled than the mere midwives of Second Clinic. Surely that fact alone should have skewed the results in the other direction. What could be happening?

Funeral for a Friend

Desperate for an explanation, Semmelweis began an exhaustive investigation of both clinics. He performed autopsies on women who had died from so-called “childbed fever” or “puerperal fever” in an attempt to understand what killed them. He noted that women who gave birth outside the hospital but were later admitted did not suffer the same disparity in infection rates, a finding that suggested that the actual process of giving birth was exposing First Clinic patients to puerperal fever.

Thinking that the methods used might be to blame, he ordered the two clinics to switch procedures. This did nothing to the mortality rate and served only to annoy the hospital staff and to earn Semmelweis a demotion. It would not be the first time his arrogance would put him at odds with the Vienna medical establishment, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Semmelweis’ breakthrough came through a seemingly random tragedy. His friend Jakob Kolletschka, a professor of forensic medicine, had been leading a student through an autopsy in the bare-handed fashion that was standard practice at the time. The student accidentally jabbed Kolletschka’s finger with a scalpel, and within days the doctor was dead. Semmelweis reviewed his friend’s autopsy records and discovered that he had suffered from exactly the same symptoms of the women who had died from puerperal fever. Could the cadaver Kolletschka was dissecting have been the source of the infections?

In a flash, Semmelweis could see the answer. Only doctors performed autopsies, and generally did them in the morning before seeing patients in First Clinic. It seemed likely that the physicians themselves were transmitting a causative agent between the autopsy suite and the birthing rooms of First Clinic. And it seemed like they were doing so with their bloody bare hands.

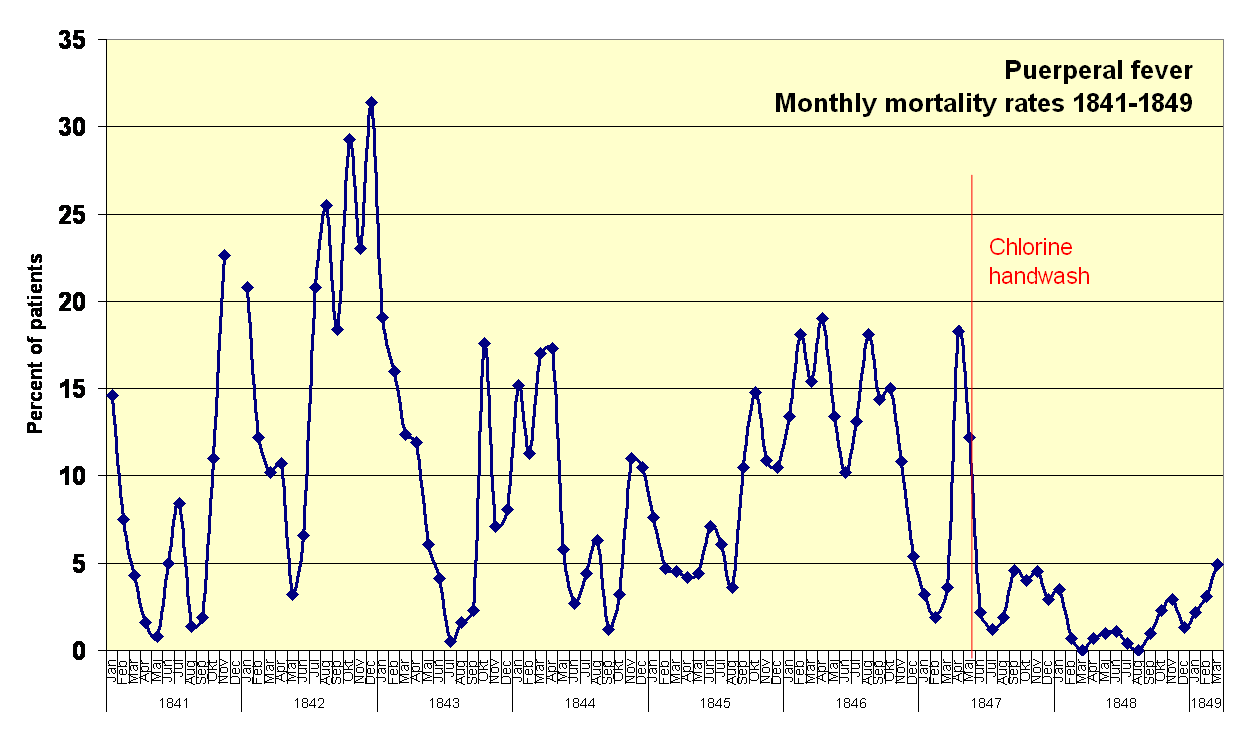

In a repeat of the move that led to his demotion, Semmelweis ruled that all First Clinic physicians must wash their hands with chlorinated lime or calcium hypochlorite, similar to common household bleach, to rid themselves of “cadaverous particles.” His First Clinic colleagues chafed at the idea — literally, as bleach is quite irritating to the skin. But they also grumbled that it was unthinkable that saintly physicians could be carriers of contagion, a theory for which Semmelweis had offered no evidence. And to make matters worse, he curried further disfavor by actively enforcing his new rule, monitoring their hygiene and calling out scofflaws.

No Good Deed Goes Unpunished

Despite the unpopularity of his new rules, the statistics were clear: as soon as hand washing was instituted, First Clinic’s mortality rate plummeted 90%. Within a few months, mortality from puerperal fever had dropped to zero. Semmelweis had been proven right, and he was saving lives.

Sadly, it was not to last. He had never been able to explain exactly how hand washing worked. It would be a few years before Pasteur formulated the Germ Theory of Disease, and so Semmelweis lacked the framework to explain his breakthrough. He just knew that it worked, and his stubborn insistence that physicians unquestioningly follow his rules grated on the establishment enough to earn him a dismissal from his post. He returned to Hungary and eventually became head of obstetrics at the hospital in Pest, where his hygiene rules drastically reduced the mortality from puerperal fever yet again. Meanwhile, back in Vienna, business returned to usual at First Clinic, and mortality skyrocketed.

For reasons unknown, Semmelweis had always refused to publish his results or even to deliver public lectures. He was eventually convinced to write a book, The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. It was part rambling history of his findings and part instruction manual for hospital hygiene, but most disturbingly, the second half was a vicious screed against those who had doubted him and his results. He went so far as to call out all those who failed to heed his rules murderers.

His book failed commercially, and he grew increasingly unstable, to the point of random crying jags in public and accosting young couples in the street to beg them to make sure their doctor washed his hands if they ever had a child. In 1865, his wife and family, concerned for his mental health, convinced him to take a holiday in Austria. When they arrived in Vienna, his wife suggested they visit an old friend at his hospital. But instead of a friendly face, Semmelweis was greeted by burly orderlies bearing a straitjacket. He had been duped into being committed to an insane asylum. Within a few days, he would be dead, possibly from injuries sustained during an escape attempt, possibly by a brutal beating at the hands of guards. In either case, he died an ironic death; his autopsy revealed death by septicemia, essentially the same disease he had spared countless women with his hand washing procedure.

Semmelweis died without ever learning of Germ Theory, which would have explained that bacteria were the mysterious “cadaverous particles” being transmitted to First Clinic patients on the filthy hands of their doctors. He died thinking that his labors had been wasted and his procedure would never be accepted by the establishment. He was at least partially to blame for this through his brusque manner, arrogant insistence that everyone obey his rules without explanation, and failure to communicate his results. That does not make his fate any less cruel, but the fact remains that he did save lives using science, and his stubbornness did eventually change medicine for the vastly better.

This is a lovely article, even though it is not one I was expecting for hackaday. It is a great lesson in not just going along with the way everyone else does things, a central concept in the hacker ethos!

Thanks!

Not to mention when you know a better way (or think you do), to carefully explain it, and to keep trying different ways of explaining it until one party or the other is convinced.

Also to be open to new ideas. Most^h^h^h^h Many of us are too used to being the smartest one in the room. :)

“To stem this practice, the hospital offered free care to pregnant women, with the predictable effect of overwhelming the physicians of the obstetrics clinic. To deal with the overflow, a second obstetrics clinic was established, staffed entirely by midwives. The two clinics quickly developed opposite reputations among the people of Vienna.”

Of note, free care most likely was something for the poor class*. Second midwives wouldn’t have been as headstrong, let alone less able to say no to hand-washing.

*If mortality was as high among the rich would our story have been different?

As far as I could see, Semmelweis never enforced the rule for the midwives, only for the doctors. He strongly correlated the fever with the cadavers, and since the midwives never came into contact with cadavers, why bother?

How long does the calling for soap and boiling water thing go back with midwives though?

My understanding is that was always to give the father-to-be something to do so he could get out of the way of the women while they worked. Possibly apocryphal, of course.

Very good!

“cadaverous particles” or bacteria, who cares … Lives were being saved and the knowledge was just ignored. How sad.

Given they’d just had their hands in a corpse it could be anything, could be particles of the sandwich the deceased ate before having a heart attack.

…or it could be bacteria, yeah.

I’ve heard it said that doctors are really terrible at heeding the results of scientific studies even now. One of the discoverers of the bacterial cause of stomach ulcers spoke about how doctors wouldn’t heed their proof. In spite of overwhelming evidence doctors continued with their accustomed ‘stress’ cause for the condition.

Reminds me how bad diagnostics can be, or lack there of even if “known why” the method is valid, in modern times.

It’s not just doctors, but medical professionals in general. One common example is the number of medical professionals who smoke (much higher number than you’d expect), despite the links to cancer and other illnesses…

“A bad idea with a good presentation is doomed eventually. A good idea with a bad presentation is doomed immediately.” (paraphrased from Akin’s Laws)

Very, very true.

Fresh young minds and adults with an axe to grind?

Capitalism reverting to 19th century rules as soon as socialism collapsed?

Good presentation: “free stuff! Eat the rich!”

One generation suffers or watches the suffering.

The next remembers

The millennials have no clue and are about to repeat it. “All praise Jeremy Corbyn our Lord and Saviour”

“Then explain bad ideas like socialism rising from the dead …”

Correlation does not imply causation.

A) Socialism was never alive in the first place. It has invariably been smothered at birth whenever it has the temerity to rear its head. Whether it is a good idea or not is a moot point. Those in power fear it far to much to allow it to live.

Socialism, like Western Civilisation, to paraphrase a probably apocryphal quotation of Gandhi might well be a good idea. We may never know.

B) Capitalism is arguably also a bad idea, as it favours greed and short termism rather than logic and co-operation.

C) This article has nothing to do with either socialism or capitalism, so please concentrate on the matter at hand.

D) Note to self… don’t feed the Trolls.

Authoritarianism is the true villain rising from the dead. In the end, it wasn’t the economic policy of hyper-corporatist Italy under Mussolini or the socialist policy in Soviet Russia under Stalin that ruined everything; behind their theories and ideals it was just authoritarianism, kleptocracy, oligarchy, corruption, the usual. The economic principles were always just for show. Something for the non-ruling class to bicker about.

Doesn’t matter if it’s capitalism or otherwise, authoritarianism is going to be the next ugly regime. As always.

Perhaps I’m being snide, but the it has been misused so much for so long,simply throwing out socialism there, with out context, a reader has no clue what you are talking about.

It gets worse..

The other doctors didn’t object to washing their hands simply because it was uncomfortable. Medical fashion of the day held that a doctor whose hands and coat were caked with dried blood looked ‘experienced’, and that patients — especially delivering mothers, since women were ‘well known’ to be ‘hysterical’ — would be reassured by seeing it.

Semmelweis wasn’t just pushing a new idea. He was telling doctors that one of their primary status symbols was a sign of lethally unprofessional sutpidity. The consensus of experts declared his reasoning unconvincing and his results insulting.

Joseph Lister faced exactly the same resistance, but had Pasteur’s germ theory and John Snow’s in-your-face data analysis of the 1854 Soho cholera outbreak to support him.

I worked my way up in the US from a volunteer firefighter/EMT to professional fire officer/paramedic and then running a large rural county fire’s EMS system as well as teaching at a college paramedic program, co-authoring and collecting research, and enforcing universal gloves policy most importantly to protect my personnel. Imagine us and all other non-physician medical practitioners like the midwives of this story who will do as commanded by our physician advisor who lends us their licensed healing powers, their remote hands in the field, rather than having our own abilities. We simply do as we are told or we are handed our exit papers and loose our certification.

I moved continents to my wife’s home country. It is beyond irritating that they do not wash or wear gloves even in the blood draw(though EMS does seem to occasionally be better here since taking on the US standard curriculum for EMT-P) and I am the idiot for suggesting they make a change even for my children(in a foreigner accent and imperfect grammar). Part of the problem is my voice drowns in a culture where everyone thinks they are an expert and the doctors running the health system are the most arrogant of all; maybe gloves are uncomfortable to them?

Perhaps arrogance and elevated status is why it has been and sometimes still is hard to get the profession to accept life saving scientific inconveniences.

What goes around, comes around. Just imagine the doctors that treat other doctors not washing their hands?

I am a regular Hungarian reader of this portal. I am greatly beholden to the author of this article. The kind really unusual here. I am proud of our Semmelweis and belive that his sad story holds much edification not especially in medicine, but for all of us. (In Hungary many hospitals are named after Semmelweis Ignác. His name is written in such a way in Hungarian.)

Dr. Semmelweis is one of my favorite examples of victims who knew the truth in pro life ways and means and was in my opinion murdered for advocating pro-life and pro-truth ways and means… especially regarding explaining clearing from having a comprehension gap either due to the cultures development or personal development.

Edit: Typo entry error; replace “clearing…” with “clearly”.

It comes down to the age old problem of: Knowing the truth and convincing others of the truth are 2 entirely different things. You can be right all day long, if nobody else sees it you’re still boned.

I wonder if the problem could also have been solved by moving the autopsies to the last procedure of the day before the doctors went home. It would have had the same effect and probably the doctors would complain less.

Depends on what the doctors were doing after work, how they got home and such. Maybe they could have just spread even more diseases around and infected more of the general population. Stuff that was otherwise already “washed” off the hands during the days work in the hospitals.

One of the best articles I have read on Hackaday in some time.

Thanks!

Good story, well told. Thank you Dan.

It is remarkable how slowly knowledge crept around the medical profession, especially in those days.

I believe that the first person to suggest that Puerperal fever was transmitted by the attending doctor was Alexander Gordon in his “A Treatise of the Epidemic Puerperal Fever” published half a century before in 1795.

““… that the cause of the epidemic puerperal fever under consideration was not owing to a noxious constitution of the atmosphere, I had sufficient evidence; for if it had been owing to that cause, it would have seized women in a more promiscuous and indiscriminate manner. But this disease seized such women only as were visited, or delivered, by a practitioner or taken care of by a nurse who had previously attended patients affected with the disease. In short, I had evident proofs of its infectious nature, and that the infection was as readily communicated as that of the small-pox or measles, and operated more speedily than any other infection with which I am acquainted.”

“It is a disagreeable declaration for me to mention, that I myself was the means of carrying the infection to a great number of women …”

He was nowhere near to Semmelweiss’ brilliance on using chlorine in aseptic technique but he was on the right lines with “The patient’s apparel and bedclothes ought either to be burnt or thoroughly purified; and the nurses and physicians who have attended patients affected with the puerperal fever, ought carefully to wash themselves and to get their apparel properly fumigated before it be put on again. “

More on Gordon on: https://fn.bmj.com/content/78/3/F232

To me, Gordon blazed the trail but several others followed very close together in the 1840s including Watson who advised “Whenever puerperal fever is rife, or when a practitioner has attended any one instance of it, he should use most diligent ablution; he should even wash his hands with some disinfecting fluid, a weak solution of chlorine for instance: “

Lots more on this on: Puerperal Fever in Britain: Failed Models of Disease Causation by Jessica Wells http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4879&context=etd

ps: The story that Shannon refers to is also a good one. Barry Marshall and Robin Warren tried to show the medical profession that stomach ulcers were caused by Helicobacter pylori but no-one wanted to know. In the end Marshall had to drink the stuff to prove it – and got the Nobel prize for it, a somewhat better fate than Semmelweis’ strait jacket.