The modern Internet can be a dangerous place, especially for those who might not have the technical wherewithal to navigate its pitfalls. Whether it’s malware delivered to your browser through a “drive-by” or online services selling your data to the highest bidder, its gotten a lot harder over the last decade or so to use the Internet as an effective means of communication and information gathering without putting yourself at risk.

But those are just the passive threats that we all have to contend with. What if you’re being actively targeted? Perhaps your government has shut down access to the Internet, or the authorities are looking to prevent you from organizing peaceful protests. What if you’re personal information is worth enough to some entity that they’ll subpoena it from your service providers?

But those are just the passive threats that we all have to contend with. What if you’re being actively targeted? Perhaps your government has shut down access to the Internet, or the authorities are looking to prevent you from organizing peaceful protests. What if you’re personal information is worth enough to some entity that they’ll subpoena it from your service providers?

It’s precisely for these sort of situations that the FreedomBox was developed. As demonstrated by Danny Haidar at FOSSCON 2018 in Philadelphia, the FreedomBox promises to help anyone deploy a secure and anonymous Internet access point in minutes with minimal user interaction.

It’s a concept privacy advocates have been talking about for years, but with the relatively recent advent of low-cost ARM Linux boards, may finally be practical enough to go mainstream. While there’s still work to be done, the project is already being used to provide Internet gateways in rural India.

ARM to the Rescue

There’s nothing in the FreedomBox distribution, which is based on Debian, that precludes you from running it on an old PC you have kicking around. But the project really makes the most sense when running on one of the small and cheap ARM SBCs that have popped up in recent years. It’s perhaps best to think of FreedomBox as a free and open source replacement for the traditional consumer router: you want something you can just plug in and leave on a shelf or under a desk.

There’s nothing in the FreedomBox distribution, which is based on Debian, that precludes you from running it on an old PC you have kicking around. But the project really makes the most sense when running on one of the small and cheap ARM SBCs that have popped up in recent years. It’s perhaps best to think of FreedomBox as a free and open source replacement for the traditional consumer router: you want something you can just plug in and leave on a shelf or under a desk.

It should come as no surprise that everyone’s favorite Linux SBC, the Raspberry Pi, is listed as one of the supported devices. But it’s actually relegated to the second tier of hardware support, as the project is actively being developed for the BeagleBone Black as well as variants of the OLinuXino and Cubieboard.

In the future the FreedomBox team hopes to integrate mesh networking into their software so that these tiny ARM computers could potentially be air dropped into areas struck by natural disasters to establish an emergency communications system. Danny imagines a future in which FreedomBoxes can be dropped via parachute along with food, water, and other supplies.

User Experience

Actually installing FreedomBox to your ARM computer of choice boils down to copying the image to an SD card, but that’s about the most technical part of the whole process. In the future, end users wouldn’t even have to do that much, and ideally would buy a pre-loaded SD card or even a turn-key device. To that end, Danny mentions they are actively looking for hardware partners to help produce ready-to-use FreedomBoxes in the future.

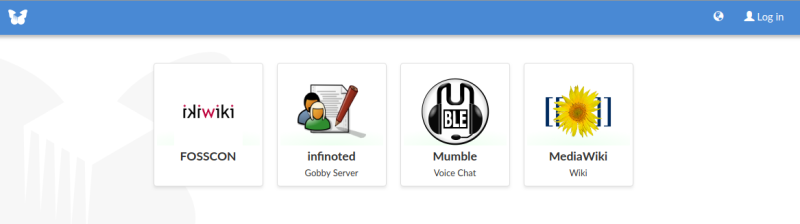

Once the FreedomBox is up and running, all management of software packages and services is done through a simplified web interface. Just click on what you want and wait a few minutes for the packages to get pulled down and activated. Services like Tor and OpenVPN can be quickly configured to use the FreedomBox as a secured “tunnel” through untrusted networks, and an array of servers are available to host content locally such as MediaWiki if the device is to be used as localized source of information rather than an Internet gateway.

In fact, keeping services local to the FreedomBox is one of the biggest goals of the project. The logic goes that putting your information into a “cloud” outside of your own control is one of the easiest ways for your information to fall into the wrong hands. But if you can keep as much of it as possible on a machine inside your own home, it would be that much harder for bad actors to get access to it.

Long Road Ahead

As you might expect, those in attendance at FOSSCON were keenly aware of many projects to secure and anonymize information, and during the Q&A portion of the presentation it seemed like everyone had a suggestion for what should be added to the FreedomBox going forward. Which is good, it’s the kind of discourse that will help make sure these devices provide the maximum benefit to their users.

But Danny did stress there is a lot of work ahead of the team. The current goal is to get the basic system working and stable, and to localize it to as many languages as possible as the devices ideally would be distributed worldwide. Features like mesh networking and full disk encryption are on the team’s roadmap, but aren’t anywhere near release. That does limit the immediate utility of the FreedomBox somewhat, but for those who are looking to quickly and easily deploy a secure server, the project is certainly worth taking a look at.

I’ll TUX all those bookmarks.

my freedombox contains much different items

Very similar to YunoHost, isn’t it?

Doesn’t seem like it. YunoHost looks like it’s to make configuring a server easier, doesn’t seem to have anything to do with privacy/security.

I read FreeDoomBox… was a bit disappointed after I clicked :D

Happened to me, too. Freedoombox sounds good to me anyway.

That is an idea for next year’s Hackaday Prize.

Looks like OpenMediaVault, only that it is targeted for smaller boards.

But why would I run this on a board with only 100Mbit Ethernet, and without SATA or M.2? (BeagleBoneBlack)

The apu1d box looks like a more logical choice, and the price seems reasonable.

The Freedombox distribution also runs fine as a VM and can be added to an existing Debian 9 installation. I have it set up with DAVdroid so the contacts and calendar and calendar on my phone are stored on a disk that I own, stored at `/var/lib/radicale/collections/$user/*` in a form I can work with if need be.

kinda reminds me of SOAP.

From Wikipedia:

SOAP (originally Simple Object Access Protocol) is a messaging protocol specification for exchanging structured information in the implementation of web services in computer networks. Its purpose is to induce extensibility, neutrality and independence. It uses XML Information Set for its message format, and relies on application layer protocols, most often Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) or Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP), for message negotiation and transmission.