The world of glues is wide and varied, and it pays to use the right glue for the job. When [Eric] needed to stick a wide and flat 3D printed mount onto the back of a PCB that had been weatherproofed with an uneven epoxy coating, he needed a gap-filling adhesive that would bond to both surfaces. It seemed like a job for the hot glue gun, but the surface was a bit larger than [Eric] was comfortable using with hot glue for. The larger the surface to be glued, the harder it is to do the whole thing before hot glue cools too much to bond properly.

What [Eric] really wanted to use was a high quality two-part epoxy that he already had on hand, but the stuff was too runny to work properly for this application. His solution was to thicken it with a thixotropic filler, which yields a mixture that is akin to peanut butter: sticky, easily spread to where it’s needed, but otherwise stays in place without dripping or sagging and doesn’t affect bonding.

Common thixotropic fillers include ground silica or plastic fibers, but [Eric]’s choice was wood flour. Wood flour is really just very fine sawdust, and easily obtained from the bag on his orbital sander. Simply mix up a batch of thin two-part epoxy and stir in some wood flour until the sticky mixture holds its shape. Apply as needed, and allow it to cure.

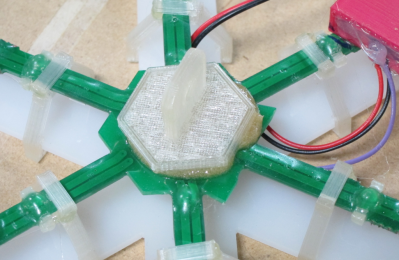

Thanks to this, [Eric] was able to securely glue a 3D printed pad to the back of his animated LED snowflakes to help mount them in tricky spots. Whether for small projects or huge installations, LEDs, PCBs, and snowflakes are a good combination.

We used wood flour with kanagon glue when I built balsa air planes when I was small and I needed to fill some gap :)

Something I’ve always wanted to know: Is there any difference, chemically, between the huge bottles of epoxy resin you can buy online and epoxy glue from name brands such as JB Weld? I guess the glue has some thixotropic filler but that can’t really explain the 20x price difference.

There’s got to be something in it. In my experience JB Weld has a thicker consistency, almost like toothpaste. The cheapo epoxy I’ve used is like water in comparison.

JB weld has talcum powder in it.

Caution: ask an actual expert; this is what I picked up when I got curious about boat-building materials and went on a long, long reading tangent.

There are a few different epoxy chemistries (bulk stuff with a long working time is generally an amine hardener, little fast-cure things are usually thiol hardeners, and your nose will tell you about that in a hurry), and a lot of variables within a single choice of reaction chemistry. The resin is usually short-chain polymers rather than monomer, the length and branched-ness of which influences viscosity, curing behavior, and final mechanical properties.

Hardeners may be small molecules (produces a thin hardener with a large resin:hardener ratio) or functionalized fragments of the same polymer as the resin (usually more viscous and lower resin:hardener ratio) as well as influencing the same variables as the resin. Then there are the additives for controlling surface tension, flow properties, cure rate, shelf stability, and who knows what else.

These are all optimized differently for different applications. Stuff sold in gallons is probably designed for laminating fiberglass, kevlar, or carbon fiber cloth, where you want smooth wet-out and fairly long working time. Little bottles are probably intended for gluing solid objects to each other, where you need viscosity to keep the glue in the joint and usually want a fast cure more than you want a long working time. Adding your own fillers can make a thinner resin work quite well as a gap-filling adhesive. Trying to thin a viscous epoxy is a terrible idea, as thinners will interfere with forming the proper structure.

The biggest factor in the price-per-volume difference between the 2 oz. bottle and the gallon jug is probably the packaging, though. I don’t think the raw material cost varies all that much among things you can get in the hardware store. Get into aerospace grade low-outgassing silicone epoxies, though, and you’ll never believe a bit of sticky goop could cost so much.

I’ve seen super cheap thin epoxy and super cheap thick epoxy. For the former, check you local economy fiberglass tooling supplier. For the latter, main company I can think of off the top of my head is polymercomposites which sells directly on eBay, probably the cheapest Max Bond formulation. I’m fairly certain the formulation is less expensive, but it’s rare for companies to need it in larger quantities, so it usually /seems/ like the 5 minute stuff is more expensive.

The thick 5-minute stuff is some sort of sulfur-containing chemistry, and I think part of it’s apparent thixotropy might just come from the fact that it’s so high viscosity to begin with and it sets so quickly that it appears to not “sag.” You can usually distinguish that chemistry by smell =P. I don’t remember the exact organic, but an MSDS should reveal it.

There are thousands of different possible epoxy formulations. I read a rather large book on the subject about 25 years ago; if I recall correctly there were 4 broad categories of epoxies, one of which was “other.”

Thickener?? In the Hot Rod 50’s we often used flour all right.. from the kitchen. Worked fine.

The Pros used ASBESTOS dust. Glad I didn’t use much of that…

It’s funny, you look up thickening epoxy on google and a lot of the results are articles saying you mustn’t use anything like sawdust or flour for this and that reason written by… epoxy manufacturers. You gotta use our crazy nanotech microballoons or whatever. Hmm no conflict of interest there.

I personally like using talcum powder. Real fine, the epoxy doesn’t seem to leach out like with coarser sawdust. Makes a real regular peanut butter consistency.

Really good to see wood flour gaining traction, I’ve been using it for years in my dentures to keep them from failing apart in front my lovely wife. The also have another interesting postive, they absord the toxic fumes present in the epoxy. This may not be useful for me but for my troubled grandson, who has a habit of huffing the stuff it has prevented him from breaking into my house and taking some for himself.

I’ve been mixing various adhesives with sawdust, I mean wood flour for years, it makes up for my lack of carpentry skills.

The silica thickeners are not ground, they are pyrolized. It has an extremely low density and nanometer range particle size. I have a 20L pail of it in the shop, and it feels like it’s empty, but it’s not. Not good to inhale though. I wear a respirator when I work with it.

Hot glue can be applied without the ‘ gun.

You can use a hairdryer to melt the stuff in-place, where you want it. Or to keep it hot after you’ve applied it with the gun anyway. The temperature needs to be just above 100 degrees C. It seems a hairdryer is aiming for just below that. Quench the airflow by restricting the (cold!) airflow with about one finger. The temperature will go up to about 110.

I generally use the hot-air-reflow station instead of the hairdryer. I then use a temp of about 200 degrees, as that works quicker. (and the glue does not yet decompose at that temperature).

Ditto that. See for example Matthias Wandel on sticking felt pads to chair legs:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rmS-8XU1-vQ

That’s fine for most situations but for 3d printed parts you’re gonna warp those buddies real good. It is a good trick to reflow hot glue though.

Hot air reflow tool works well too. It has temperature control and different sized nozzles for more precision.

Seconding this technique!

I usually don’t apply straight from the stick, as in Wandel’s video, but rather, I use scissors to dice the stick up into little “coins” or slice it into thin slivers, and place them where I want the glue. If they blow away when I start with the hot-air, I’ll melt the corner of each one and tack it into place before beginning the overall heating.

Of course, I could just dispense the glue from the gun, not worry about cooling, and then use a heat-gun to re-melt the whole thing for final assembly. But the chief benefit of the cut-and-place technique is there are NO STRINGY BITS to get everywhere.

I have used wod flour and epoxy for years to fix furniture. Just the other day I suggested it to a fellow youtube user for helping to hide the cracked spot on a vintage guitar neck he repaired. You can use it on small repairs to hide cracks as you can get a very good color match, and you can also use it where larger pieces of material are missing. You can hand sculpt it to take on the basic shape and finish it with files and sandpaper. Bigger spots don’t look as good as small repairs but it works great for less cosmetically sensitive areas.

One caution for using your own shop as a source of wood flour: make sure it’s all fine particles if you’re bonding large surfaces. Sanding dust usually has larger fragments mixed in, which can prop the joint open and drastically reduce the actual bonding area unless you lay down a rather thick layer of epoxy. Filtering those out can be rather tedious. Commercial wood flour is already well filtered, and is often dirt cheap.

Why not just use dirt?

A friend of mine which works at a local electronics shop, told me that was possible to create a strong cement-like compound by alternating layers of cyanoacrilate and baking soda.

Baking soda rapidly cures cyanoacrylate. That’s less of a mix and more of an accelerant. The downside is that it’s really white and noticeable compared to straight super glue.

There are a ton of fillers:

glass balloons (micro balloons) super light.

Flox kind of a dinner filler has some strength for joining parts.

Silica, makes things hard, tough to work with.

Various flours, wood and grain. They are very fine.

Saw dust is way coarse, but may add strength.

The stuff used with fiberglass is probably a polyester, not an epoxy. If the two components are to be mixed in more-or-less equal amounts, it’s probably epoxy; if the “hardener” (really a catalyst) is just a small percentage of the total, it’s probably a polyester.

The West Systems Epoxy that I’m using in the article is mixed in a 5:1 ratio.

I install epoxy and other resinous floors for a living, when we need to thicken epoxy we use fumed silica as it doesn’t really change the appearance of the product, it also makes it cure faster.

Whatever happened to “microballoons”. Forgotten tech? Basic.