[Mike Gardi] credits his professional successes in the world of software development on the fact that he had access to logic-based educational games of a sort that simply don’t exist anymore. Back in the 1960s, kids who were interested in electronics or the burgeoning world of computers couldn’t just pick up a microcontroller or Raspberry Pi. They had to build their “computers” themselves from a kit.

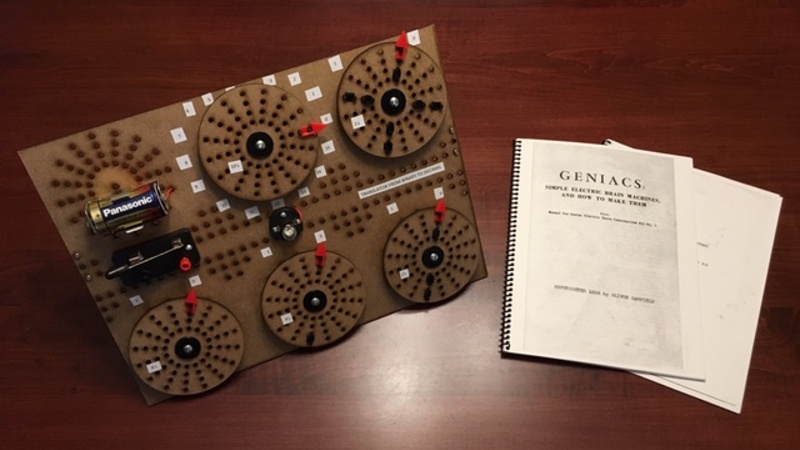

One of those kits was the GENIus Almost-automatic Computer (GENIAC), a product which today is rare enough to essentially be unobtainable. Using images and documentation he was able to collect online, [Mike] not only managed to create a functioning replica of the GENIAC, but he even took the liberty of fixing some of the issues with the original 60-odd year old design.

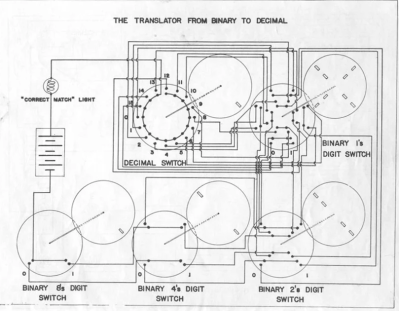

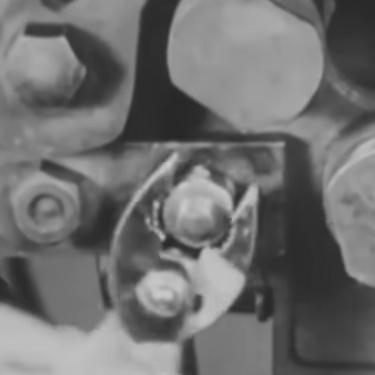

Fundamentally, the GENIAC is composed of rotary switches which feed into each other to perform rudimentary logical functions. With banks of incandescent bulbs serving as the output, users could watch how placing the switches in different positions would influence the result.

Fundamentally, the GENIAC is composed of rotary switches which feed into each other to perform rudimentary logical functions. With banks of incandescent bulbs serving as the output, users could watch how placing the switches in different positions would influence the result.

This might seem a little silly to modern audiences, but thanks to a well written manual that featured a collection of compelling projects, the GENIAC managed to get a lot of mileage out of a couple light bulbs and some wire. In fact, [Mike] says that the GENIAC is often considered one of the first examples of an interactive electronic narrative, as the carefully crafted stories from the manual allowed players to go on virtual adventures long before the average kid had ever heard of a “video game”. A video about how one of these stories, “The Uranium Shipment and the Space Pirates“, can be seen after the break. Even today it would be an interesting enough toy, but back in 1955 it would have been mind-blowing.

Construction of this replica will require access to a laser cutter so you can approximate the original’s drilled Masonite backing and rotors. From there, [Mike] has produced an array of 3D printable components which are attached to the board to serve as contacts, spacers, and various other pieces of bric-a-brac. Some of the parts he couldn’t find pictures of, so he was forced to come up with his own designs. But considering the finicky nature of the original, he thinks his printed parts may actually be better than what the toy shipped with.

If you like his work with GENIAC, be sure to check out the 3D printed replica of “The Amazing Dr. Nim” that [Mike] made last year, or his breathtaking recreation of the Minivac 601.

[Thanks to Granz for the tip.]

I saw a book on how to build one of those “computers” Not this one specifically, I think. It was around 1997.The local collage had a thin blue volume on a kid’s “almost automatic” computer. It was organized like a typewriter, with a flat body, & a round cylinder at one side. I don’t remember quite how it worked.

I just searched the library on-line. Doesn’t look like they have the book any more, but it also doesn’t list Jimi Hendrix’s sci-fi anthology. So-

That’ll be the paperclip computer as mentioned here:

https://www.evilmadscientist.com/2013/paperclip/

There’s a link in there to an online copy. (How to Build a Working Digital Computer (1967) by Edward Alcosser, James P. Phillips, and Allen M. Wolk)

I found that in the library when I was in grade 8.

By that, I mean that they also had Jimi’s book of hand-picked sci-fi stories, and now that’s gone. So, they probably went to the local book sale. I bought some amazing books at that sale.. COBOL, complete with 70s receipt from a book store across the country.

Sorry buddy, lame attempt at recovery! Now everyone knows that you’re from a different time branch where Jimi Hendrix is a Sci-Fi author!

He’s probably referring to Jimi’s favorite book, the Penguin Omnibus of Science Fiction.

The phrase “Purple Haze” comes from a science fiction novel by Philip Jose Farmer (Night of Light).

He’s probably referring to Jimi’s favourite book, the Penguin Omnibus of Science Fiction. Hendrix was a big Sci-Fi fan, which can be seen in many of his songs – the phrase “Purple Haze” comes from “Night of Light” by Philip Jose Farmer.

“Construction of this replica will require access to a laser cutter so you can approximate the original’s drilled Masonite backing and rotors. ”

Or, you know, a drill and a saw? Like the original was done? Seriously.

Drill? Saw? Are you totally mad?! These are hand tools! No one uses them anymore! You are crazy! Just laser-cut, CNC mill or 3D print it, like all the “REAL” makers!

I’m pretty sure the original Masonite pieces were milled or stamped somehow. Certainly not made by hand.

Even in the 1950s, they wouldn’t have made these by hand. There must have been a stamp, or some kind of jig.

Unless you know an easier way to make one of those, laser cutter it is. If you want to take the time to try and cut all that out and drill all those holes yourself, be my guest.

But it’s not going to look the same, and certainly not as good, and that’s kind of important when making a replica.

Mom was a mathematician (and early computer programmer) and Dad was an electrical engineer, I was born in the mid-50s, so I had an interesting set of toys and games, including a Mr. Machine, GENIAC, CARDIAC, Dr. Nim, DigiComp I, and later a MUSE synthesizer (originally gifted to Dad by Marvin Minsky himself). Sadly, all of these went into a dumpster (along with a PDP-8, Sun 1, and other things I had accumulated in my early programming career) when I cleaned out the house following their deaths in the early 90s. By the way, we’re African-American, kind of an oddity back then, but not so much as you might think.

I credit a lot of my ability and knowledge to my father being an electronic tech, and my mother also being an early computer programmer. I was born in ’62 and learned a lot from them and the encouraging environment they made sure that my sister and I had. My first computers were built my myself with relays and small scale ICs, then later a 6800 and an 2650 (great chip, but it could only address 32K of memory, sad.)

I hadn’t heard of the Triadex Muse, that might be the saddest loss of the bunch.

I found a browser based emulation of it here: http://www.till.com/articles/muse/

I remember a bit about something in Popular Electronics, I thought with “Muse” inthe name, but usung a pseudo random generator.

I do know that the first issue of Popular Electronics I bought was Feb 1971, and Don Lancaster hadhis “Psych-Tone” on the cover, a pseudo random generator controlling a VCO, with envelope shaping and some level of filtering.

I did breadboard it, lots of fun for someone with no musical skill.

I’m sure I later saw somecommercial product that it seemed based n.

Michael

About 1968 or 69 the !ocal paper had a short article about two kids who uilt their own comouter. From that point on, I wanted one. I did start reading about electronics and radio shortly after.

Withina s decade, there werehome computers. I hadtowait till 1979 because I didn’t have the money. Even then, I got a KIM-1 because someone attended a seminar, I’m sure paid for by work, and didn’t want the computer afterwards, so I got it.

It was much later that I realized those kids hadn’t built an electronic computer likeI imagined, but was something like a Digi-Comp. So even if I’d copied those kids in 69, I’d not have the comouter I imagined.

My parents were zoologists, so no comouter help from them, though I probably got to do a few uncommon things as a result.

Michael

I grew up in the late 50’s/early 60’s and had a Geniac also. As I recall it wasn’t the greatest quality. Seems that the times generated all sorts of great children’s technology toys. I can remember the metal key on Mister Machine cutting into my fingers as I wound him up. We had chemistry sets to play with, Lawn Darts and all manner of cool but dangerous toys. It’s a wonder we made it to adulthood. Wouldn’t change the experience for anything.

I grew up in the 1960s, and loved my GENIAC. I still have the Masonite boards and discs in a box somewhere in my basement, but the original porcelain lampholders, battery holders, and little brass contacts are all long gone, except for whatever remains in the switches from the last thing I built. I agree that the most important component was the instruction manual, which helped introduce several ways of wiring the switches to solve problems.

You’re in a good position to answer the question asked above then. If you find the discs, can you examine them closely and determine if they were stamped, punched, drilled, sawed or whatever?

I was able to see the box where I stored it earlier this summer, but it’s inaccessibly buried beneath our basement stairs, and I’m simply not interested in playing tote-tetris tonight just to haul it out. However, I played with the Geniac for many years, long enough to have it etched in my memory.

The holes in the rotary switch discs were produced in a very precise pattern. They had to be, or the holes in the wheels wouldn’t have lined up with the hole pattern on the main board. For every 16th of a rotation, all the holes in all the spokes had to line up perfectly, or the multiple contact switches would have been misaligned, and the circuits would not have worked. And all the discs had to be a perfect match for each other as well, as the discs weren’t paired to specific holes on the main board.

I’m guessing now, but they were possibly drilled with a four-spindle drill head to maintain precision spacing between the inner and outer rings of holes (the brass contactor tabs had to fit perfectly in the distance between the rings of holes along the spokes), and the masonite piece mounted to a rotary indexing table with 16 stops.

It’s also possible that a steel template was originally drilled out, and then a stack of masonite boards were clamped together and drilled manually through the holes in the template with an ordinary drill press. This seems fairly likely for the main board, which had a specialized row of holes down the middle to accommodate the light bulbs, battery clips, and other terminals, but none of which needed the same critical tolerances as the rotary switches.

The outside edges of the disks were very smooth and squarely perpendicular, and seemed like they may have been stacked up and finished on a fine grained disk sander. There’s no evidence of sawtooth marks on the edges. There’s no rounding of the edges indicating that the individual disks were each sanded by hand. And there’s no visible separation of the fibers along the edges, implying they weren’t die cut or stamped.

Thanks for taking the time for such a thorough reply. I created cut files for the base and disks by bringing in a photo to Fusion 360 as a “canvas” (background image) and using it to lay out the holes. I can tell you that all of the holes were very regularly spaced as I only sketched a few holes manually and used move/copy and rotate commands, using precise dimensions, to create the rest. They always lined up perfectly with the photo when I did this.

When I was building the replica I could not find a clear picture of the brass jumpers attached to the discs. Could I trouble you to post one?

The jumpers were stamped from brass spring sheet. When flat, they are kind of in the shape of a Chevrolet bowtie logo (only with not-sharp tips). The body was formed with a rounded hump facing the contacting brass screw heads, and the tips folded 90 degrees in the opposite direction of the hump, for passing through the holes in the switch disks, where they would be folded over like staples or brads to be held in position.

When I dig it out, I will take some photos. I’ll also try to flatten and measure one, assuming the brass isn’t corroded to the point of brittleness. But not today.

Al Williams was kind enough to send me a picture of the jumpers from his GENIAC. I have updated the Instructable with the picture. He also may have found a source for said jumpers or should I say staples:

https://www.weaverleathersupply.com/catalog/item-detail/015s4-bp/15s4-loop-staples/pr_1874

I’m trying to find a source where I can get a few to try out.

My folks bought me one of these and we couldn’t figure it out. Later, it was very clear to me how it was supposed to work but I didn’t have it anymore. I bought one on e-bay a few years ago but need new bulbs for it. If you need pictures of anything (I think I have brass jumpers) e-mail me.

I would love to see a picture of the brass jumper for sure. Some of the other parts too like bulb sockets and switch. Thanks so much for the offer. Not sure where to find your email address though.

alwilliams@hackaday.com ;0

I’ll leave this here http://tinyurl.com/yxcm2ecr

Very cool.

Pretty sure I have one stashed behind my parents’ furnace. As a kid I managed to make some blinkenlights then got bored after a few hours. Keep in mind this was the mid-90’s so a few lights and wires weren’t as entertaining as an Atari Lynx.

If anyone needs STLs for restoration my local library has a 3D scanner that’s free to use.

I do think that’s it! I didn’t recognize the name, but that’s the book & machine as I remember it! Brilliant!:D