We are saddened to report that William English, co-inventor of the computer mouse, died July 26 in San Rafael, California. He was 91 years old.

Every piece of technology starts with a vision, a vague notion of how a thing could or should be. The computer mouse is no different. In fact, the mouse was built to be an integral part of the future of personal computing — a shift away from punch cards and mystery toward a more accessible and user-friendly system of windowed data display, hyperlinks, videoconferencing, and more. And all of it would be commanded by a dot on the screen moving in sync with the operator’s intent, using a piece of hardware controlled by the hand.

The stuff of science fiction becomes fact anytime someone has the means to make it so. Often times the means includes another human being, a intellectual complement who can conjure the same rough vision and fill in the gaps. For Douglas Engelbart’s vision of the now-ubiquitous computer mouse, that person was William English.

William English was born January 27, 1929 in Lexington, Kentucky. His father was an electrical engineer and William followed this same path after graduating from a ranch-focused boarding school in Arizona. After a stint in the Navy, he took a position at Stanford Research Institute in California, where he met Douglas Engelbart.

Engelbart showed William his notes and drawings, and he built the input device that Englebart envisioned — one that could select characters and words on the screen and revolutionize text editing. The X/Y Position Indicator, soon and ever after called the mouse: a sort of rough-yet-sleek pinewood derby car of an input device headed into the future of personal computing.

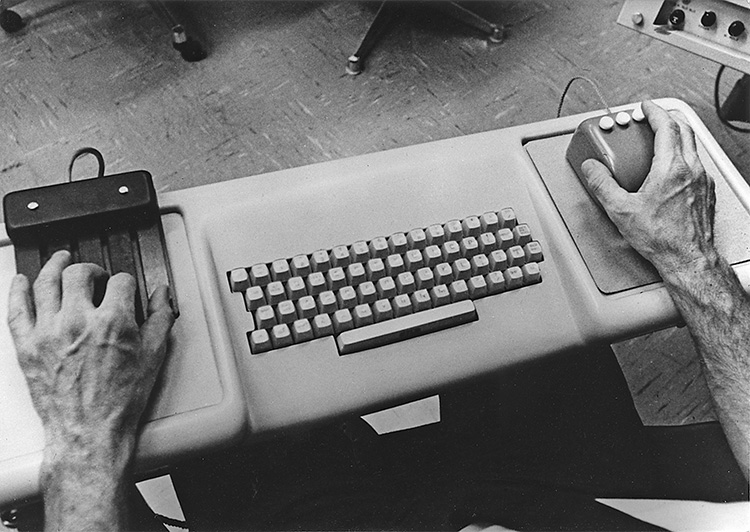

William’s mouse was utilitarian: a wooden block with two perpendicular wheels on the bottom, and a pair of potentiometers inside to interpret the wheels’ X and Y positions. The analog inputs are converted to digital and represented on the screen. The first mouse had a single button, and the cord was designed to run out the bottom, not the top.

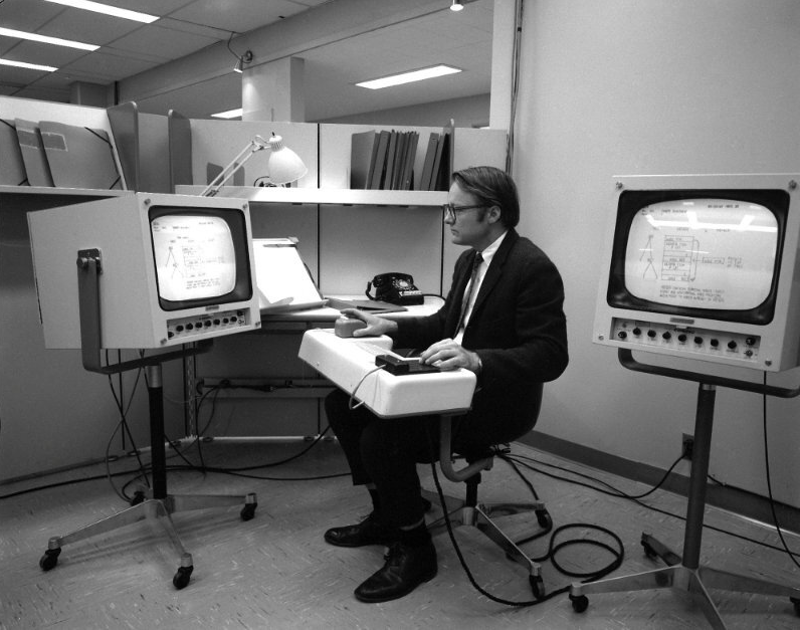

This controller was designed to steer Engelbart’s magnum opus, an experimental computer dubbed oN-Line System, later NLS, which turned out to be a great prognosticator of modern networked computing. Engelbart and English presented the many facets of the NLS in a legendary demonstration given December 9th, 1968 in San Francisco. This event, known as the mother of all tech demos, was well covered by our own [Dan Maloney] in a biographical/Retrotechtacular mash-up marking the 50th anniversary. By the time they gave the demo, the mouse had three buttons and sat atop a stately chair-mounted lap console designed by Herman Miller. This NLS console contained an IBM Selectric keyboard and held a 5-button chording keyboard on the left side.

Bill designed all the audio-visuals for the demo, set everything up, and staged the 90+ minute presentation by speaking to Englebart and others through headsets. The show was only possible from a technical standpoint because Bill had a chance encounter with a Silicon Valley phone technician and convinced him to set up a wireless link for voice and video between the hall and their lab some 30 miles away in Menlo Park. That, plus the giant Eidophor projector they borrowed from NASA to show the demo to the hundreds of engineers in attendance. English and Englebart discuss the NLS, the Eidophor, and much more in the interview embedded below, but the topic is worth much a much deeper dive (something Mike Harrison did for his talk at the 2016 Hackaday Belgrade conference).

In 1971, Bill left Stanford Research Institute for Xerox’s famed Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) where he continued to develop the features of the NLS into the Alto. You likely know the story from here — Bill Gates and Steve Jobs both toured PARC, both saw the Alto, and both steered the personal computer toward their own vision.

Main and thumbnail images via NYT

Rest in Peace Father of all Demos.

Also Wilford Brimley.

I had to go and listen to Imus’s Christmas oatmeal spoof after I heard Wilford died. RIP all of them.

Probably also the guy that started the braided fad for computer cables. (see mouse cable in picture)

I think that had been around at least 50 years longer.

I mean hey.. if you’re making a prototype and you don’t have any factory-bundled cable with the right number of conductors, it’s pretty easy to braid wires to keep them neat. Plus maybe it cuts down on EMI somewhat. Who knows.

Yeah, no. Textile insulation was the first insulation used for electrical wires.

That’s a shielded cable with a transparent sleeve, common stuff back then.

Let’s all have a piece of cheese in his honour… no wait, that’s not right.

I just waggled my mouse pointer in a ‘BE’ pattern in his honour. It seemed fitting.

What I never noticed before, just did in this video: the wheels on the proto-mouse weren’t endless encoders, but potentiometers with endstops. The original vision (or at least this realization) was a mapping of a bounded physical space on the desktop to the screen.

I wonder if that’s cool or annoying to have a physical stop that corresponds to the physical edge of the screen.

You would have to zero it into a corner every once and a while if you lift it at all.

I used to have a serial Wacom tablet which could also work as a mouse. In addition to the pen, you got a mouse and the tablet would detect a tool change and emulate a mouse. It was optional to enable absolute positioning in this mode. It seemed like an interesting idea, but it was absolutely impossible to use it that way. The notion that a mouse is a relative pointer is just way too deep.

One could also say that English’s mouse is closer to an analog joystick with return springs removed.

Have one, except USB.

I don’t think it would be that annoying provided the pots stayed collimated with screen edges. At least not for desktop use, only thing really that would be a problem in would be FPS games, or other FP environments.

In that case, why not realise it as a pantograph arrangement? Intriguing.

I keep meaning to build one of those to play with. Temporarily mislocated ie lost, my Ciarcia’s Circuit Cellar build details for one. He called it a digitiser I think, and they were oft referred to as that, for use of tracing pics into PCs.

Back in high school a friend and I built a homemade version of the VersaWriter for his Apple ][.

We saw them advertised in BYTE but they were completely unaffordable so we did our own. We used two pots for the elbow and shoulder joints, and he wrote the software and trig for calculating the end pointer. It worked but we didn’t have wirewound pots so it was pretty rough.