Decades ago, Einstein predicted the existence of something he didn’t believe in — black holes. Ever since then, people have been trying to get a glimpse of these collapsed stars that represent the limits of our understanding of physics.

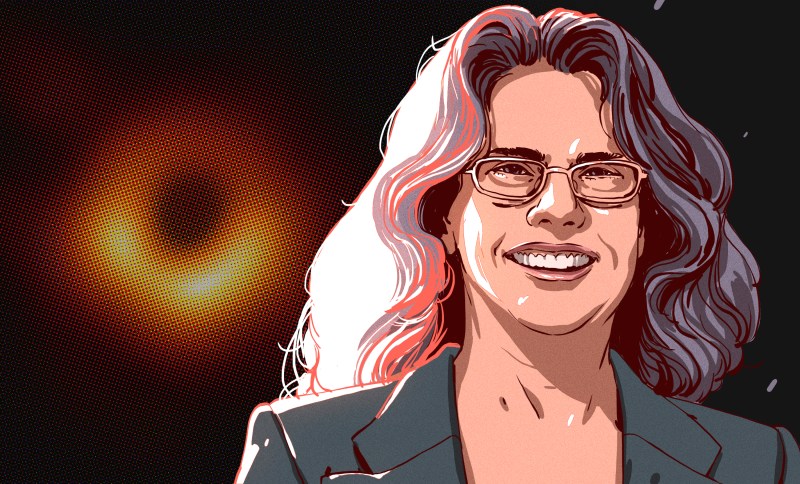

For the last 25 years, Andrea Ghez has had her sights set on the black hole at the center of our galaxy known as Sagittarius A*, trying to conclusively prove it exists. In the early days, her proposal was dismissed entirely. Then she started getting lauded for it. Andrea earned a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008. In 2012, she was the first woman to receive the Crafoord Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Now Andrea has become the fourth woman ever to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics for her discovery. She shares the prize with Roger Penrose and Reinhard Genzel for discoveries relating to black holes. UCLA posted her gracious reaction to becoming a Nobel Laureate.

A Star is Born

Andrea Mia Ghez was born June 16th, 1965 in New York City, but grew up in the Hyde Park area of Chicago. Her love of astronomy was launched right along with Apollo program. Once she saw the moon landing, she told her parents that she wanted to be the first female astronaut. They bought her a telescope, and she’s had her eye on the stars ever since. Now Andrea visits the Keck telescopes — the world’s largest — six times a year.

Andrea was always interested in math and science growing up, and could usually be found asking big questions about the universe. She earned a BS from MIT in 1987 and a PhD from Caltech in 1992. While she was still in graduate school, she made a major discovery concerning star formation — that most stars are born with companion star. After graduating from Caltech, Andrea became a professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA so she could get access to the Keck telescope in Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

The Center of the Galaxy

Since 1995, Andrea has pointed the Keck telescopes toward the center of our galaxy, some 25,000 light years away. There’s a lot of gas and dust clouding the view, so she and her team had to get creative with something called adaptive optics. This method works by deforming the telescope’s mirror in real time in order to overcome fluctuations in the atmosphere.

Thanks to adaptive optics, Andrea and her team were able to capture images that were 10-30 times clearer than what was previously possible. By studying the orbits of stars that hang out near the center, she was able to determine that a supermassive black hole with four millions times the mass of the sun must lie there. Thanks to this telescope hack, Andrea and other scientists will be able to study the effects of black holes on gravity and galaxies right here at home. You can watch her explain her work briefly in the video after the break. Congratulations, Dr. Ghez, and here’s to another 25 years of fruitful research.

Kristina, I noticed that there is under representation of left-handed persons in your biography article series. Can it be corrected in future? Thanks.

Absolutely. Do you have any suggestions?

Maybe particle related subject, interesting biography case of nuclear physicist

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fidel_Castro_D%C3%ADaz-Balart

Sort of a justice to satisfy those who quantify fairness based on a sexist norm. We can compensate all women of the past by extra compassion towards women of the present. Can you put this into measurable terms?

Filed under vacuous nonsense.

What makes you think that there is under representation of left-handed persons in the article series? How could you tell?

I believe it is a troll on feminine under-representation in science. But Kristina handled it well.

It’s a sinister plot!

Nice.

Right?

By those who turn widdershins.

I’m saddled with a deal propensity, although I mouse widdershins.

deal —> deasil

Damn autocorrect!

To be honest, when I first read the article, I was like “hey! Genzel also got it, and I think his first papers on the topic came before Ghez’s. What gives?”

See, I am biased: I’ve made my PhD at the institute Genzel works at (albeit in an unrelated group).

Then I read Kristina’s article and stumbled over one thing:

> Now Andrea has become the fourth woman ever to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics for her discovery.

Mind blown.

“What? Really? Just four? That can’t be right!”

Thing is: we happened to be in fact halfway gender balanced at our institute. And at conferences. And there are loads of groundbreaking discoveries in astronomy and astrophysics by female astronomers I could name.

Turns out Kristina is right (of course): less than 2% of Nobel physics prizes went to female colleagues.

Something _is_ off there. Was off in the beginning of the Nobel prize, but continued to be off for a long time. Still is off, seems like.

Kudos to Ghez.

Kudos to Kristina to write an interesting timely portrait in a series that just happens to point that out along the way. I had no idea.

Unless you count Marie Curie winning twice as two women…

You haven’t noticed that though

“Ever since then, people have been trying to get a glimpse of these collapsed stars that represent the limits of our understanding of physics.”

I see what you did there. :-p

Thanks for the story, Kristina. I just forwarded it to my 15 yr old granddaughter who likes math and science. 😁

I recently watched Andrea Ghez being interviewed by Brian Greene about the gravitational waves discovery. It’s such an interesting subject, and she talks about it very well.

Knowing Andrea personally I can say one thing… She totally deserved the Nobel!

It is not just her science which justifies the award, but everything else she does. She is a tireless advocate for science, doing lectures and documentaries, getting out of the ivory tower and into the community. She mentors young astronomers, particularly women, passing along her thirst for knowledge. Plus she is just a really nice person.

Another smart lady. Not sure if left handed.

https://www.saraseager.com/