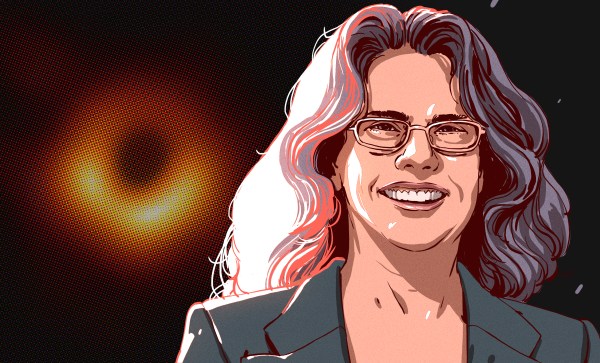

Decades ago, Einstein predicted the existence of something he didn’t believe in — black holes. Ever since then, people have been trying to get a glimpse of these collapsed stars that represent the limits of our understanding of physics.

For the last 25 years, Andrea Ghez has had her sights set on the black hole at the center of our galaxy known as Sagittarius A*, trying to conclusively prove it exists. In the early days, her proposal was dismissed entirely. Then she started getting lauded for it. Andrea earned a MacArthur Fellowship in 2008. In 2012, she was the first woman to receive the Crafoord Prize from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Now Andrea has become the fourth woman ever to receive a Nobel Prize in Physics for her discovery. She shares the prize with Roger Penrose and Reinhard Genzel for discoveries relating to black holes. UCLA posted her gracious reaction to becoming a Nobel Laureate.

A Star is Born

Andrea Mia Ghez was born June 16th, 1965 in New York City, but grew up in the Hyde Park area of Chicago. Her love of astronomy was launched right along with Apollo program. Once she saw the moon landing, she told her parents that she wanted to be the first female astronaut. They bought her a telescope, and she’s had her eye on the stars ever since. Now Andrea visits the Keck telescopes — the world’s largest — six times a year.

Andrea was always interested in math and science growing up, and could usually be found asking big questions about the universe. She earned a BS from MIT in 1987 and a PhD from Caltech in 1992. While she was still in graduate school, she made a major discovery concerning star formation — that most stars are born with companion star. After graduating from Caltech, Andrea became a professor of physics and astronomy at UCLA so she could get access to the Keck telescope in Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

The Center of the Galaxy

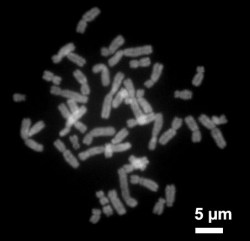

Since 1995, Andrea has pointed the Keck telescopes toward the center of our galaxy, some 25,000 light years away. There’s a lot of gas and dust clouding the view, so she and her team had to get creative with something called adaptive optics. This method works by deforming the telescope’s mirror in real time in order to overcome fluctuations in the atmosphere.

Thanks to adaptive optics, Andrea and her team were able to capture images that were 10-30 times clearer than what was previously possible. By studying the orbits of stars that hang out near the center, she was able to determine that a supermassive black hole with four millions times the mass of the sun must lie there. Thanks to this telescope hack, Andrea and other scientists will be able to study the effects of black holes on gravity and galaxies right here at home. You can watch her explain her work briefly in the video after the break. Congratulations, Dr. Ghez, and here’s to another 25 years of fruitful research.