When the news broke recently that communications had finally been re-established with Voyager 2, I felt a momentary surge of panic. I’ve literally been following the Voyager missions since the twin space probes launched back in 1977, and I’ve been dreading the inevitable day when the last little bit of plutonium in their radioisotope thermal generators decays to the point that they’re no longer able to talk to us, and they go silent in the abyss of interstellar space. According to these headlines, Voyager 2 had stopped communicating for eight months — could this be a quick nap before the final sleep?

Thankfully, no. It turns out that the recent blackout to our most distant outpost of human engineering was completely expected, and completely Earth-side. Upgrades and maintenance were performed on the Deep Space Network antennas that are needed to talk to Voyager. But that left me with a question: What about the rest of the DSN? Could they have not picked up the slack and kept us in touch with Voyager as it sails through interstellar space? The answer to that is an interesting combination of RF engineering and orbital dynamics.

Below the Belt

To understand the outage, one needs to know a little about the Deep Space Network and how it works. I discussed this in detail in the past, but here’s a quick summary. The DSN is comprised of three sites: Madrid in Spain, Goldstone in California, and the site in Canberra, Australia. Each site has an array of dish antennas ranging from 26 meters in diameter to a whopping 70-meter dish. The three sites work together to provide a powerful communication infrastructure that has supported just about every spacecraft that has been launched in the last 50 years or so.

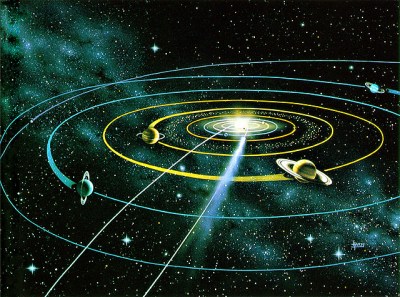

What’s interesting about the DSN sites is their geographic arrangement. Looking down on Earth from the north pole, the DSN sites are spaced almost exactly 120° apart. This means that each site’s view of the sky overlaps the other about 300,000 km into space, thus providing round-the-clock coverage for every space probe. But space travel is not necessarily only two-dimensional, and that’s where the geographic oddities of Earth and curiously, the birth of the solar system itself, play into the recent Voyager blackout.

Almost everything that orbits the Sun does so in a pretty well-defined plane called the ecliptic. The ecliptic plane is likely a remnant of the early disk of dust and debris that eventually congealed into our Sun and the planets. The only major body in the solar system that varies appreciably from the ecliptic is Pluto, whose orbit is inclined about 17° to the ecliptic. The Earth is pretty much always in the ecliptic, and therefore anything that leaves Earth is pretty much going to stay in that plane too, unless provisions are made to alter its orbit.

And that’s exactly what happened with the Voyager twins. Launched to take advantage of a quirk in orbital alignment of the outer planets that occurs only once every 175 years, the Voyager probes were able to complete their Grand Tour because each planetary encounter was planned to give the probes a gravitational assist, flinging them on to their next destination. Both probes remained very close to the plane of the ecliptic for the first part of their journey before intersecting the orbit of Jupiter and picking up speed for the trip to Saturn.

At Saturn, the twin probes would part to carry on very different missions. To get a good look at Saturn’s moon Titan, Voyager 1 approached the planet from below the ecliptic, coming under the south pole. The gravitational assist put it on a trajectory aimed above the ecliptic plane, in the general direction of the constellation Ophiuchus. Voyager 2, however, continued on in the ecliptic, using its gravitational assist to shoot first to Uranus, and eventually to Neptune. There, in the mirror of the trick its twin used to explore Titan, Voyager 2 flew over the north pole of Neptune, which put it on a path to fly close to its moon Triton and on in the general direction of the constellation Sagittarius.

Hello, Canberra Calling

It was this last move that would eventually make Voyager 2 completely dependent on Canberra for communications. Canberra is the only DSN site that lies below the equator, and even though the plane of the equator and the ecliptic are not coplanar — they differ by the roughly 23° tilt of the Earth’s axis — eventually Voyager would get so far below the ecliptic plane that none of the northern hemisphere DSN sites would have line-of-sight to it.

Luckily, Canberra is well-equipped to support Voyager 2. As the probe streaks away from home at 55,000 km/h, with its fuel slowly decaying, Voyager is getting harder and harder to talk to. The giant 70-m dish at Canberra, dubbed DSS-43, provides the gain needed to blast a signal powerful enough to cross the 17 light-hour gap between us and Voyager. Interestingly, Richard Stephenson, a DSN controller at Canberra, reports that although the smaller 34-m dishes at the complex can still be used to radiate a control signal to Voyager, such contacts are “spray and pray” affairs that may or may not be received by the probe and acted upon. Only DSS-43 has the power and gains to still effectively command the spacecraft.

Despite its importance in continuing the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM), DSS-43 was showing its age and had to be scheduled for repairs. As we reported back in July, the big dish was taken offline in March of 2020 and has been getting upgrades ever since. After eight months the repairs have progressed to the point where DSS-43 could try out a simple command link to Voyager 2 — just a basic “Are you still there?” ping, which was sent on October 29.

Happily, despite the fact that Voyager had crossed an additional 300 million kilometers of interstellar space in the meantime, the probe returned confirmation of the command almost a day and a half later. There are still a number of DSS-34 upgrade tasks to complete before the antenna is returned to full service in January of 2021, but it seems like the controllers just couldn’t bear to be out of touch with Voyager any longer.

If you want to keep up on progress on DSS-43 specifically and the goings-on at DSN Canberra in general, I highly recommend checking out Richard Stephenson’s Twitter feed. He’s got a ton of great tweets, plenty of pictures of the big dishes, and a wealth of insider information. And a hearty thanks to him for pitching in on this story, and to all the engineers making the DSN continue to deliver important science.

Great story. Thanks for sharing, Dan.

I wonder what the practical limit is in terms of the amount of radioactive isotope that can be included on a probe like this to power any future ones even longer into the future?

I think the limit is primarily dictated by the amount on radiation you are willing to release in earth, if the rocket experiences a ‘rapid unplanned disassembly’ during launch…

These things are designed to survive a RUD :-P

Would it also survive what follows next, say high-speed re-entry or ground impact?

Not an issue. We’ve had rocket explosions of probes that used Nuclear RTGs before. The RTG was recovered intact afterwards. You can design an RTG to survive a rocket explosion. Its not like it has any sensitive fragile components. It’s literally a lump of metal encased in metal.

Slightly under the critical mass. ;)

Even with long lasting radioisotope heat generator, the Seeback generator itself would still degrade a lot during its lifetime. It is subjected to both thermal, particle and gamma radiation afterall.

Practically?

Politics. Politicians need to be willing to allocate money for enrichment facilities, processing and procurement. That is a big no-no in most of EU and also in US. Eco pressure groups have more pull than scientists, by a huge margin.

Technically?

Critical mass and rocket fairing diameter.

it’s not the amount that’s the problem. It doesn’t get “used up”. The Plutonium has a half-life of hundreds of thousands of years.

The semiconductor that converts the temperature difference into electrical energy degrades over time, it oxidizes and loses efficiency.

So you have a falling curve of power output. To make it last longer, you have to make it bigger, and heavier, which means less instruments or fuel on the probe. It’s a balancing act.

The plutonium for RTGs actually only has an 87.7-year half-life. It has to be kind of short, because the half life also determines the amount of heat produced; the shorter the half life, the more heat is produced. But there’s also degradation to deal with in the thermopile, I’m sure.

We also just plain don’t have that much of it; you basically have to make it specifically by extracting neptunium from used nuclear fuel and then bombarding it with neutrons to synthesize 238Pu. We have a few kilograms of it and most of it’s now out of spec.

Build the probe in stages outside of earths orbit?

Yummmmmm…… After Eight…

I know this is going to cause a “groaner” but…maybe V’Ger wanted to talk to its’ creator after being away for a while. ;) Okay, back to hiding.

+1

Lurked here off and on forever, leaving my first comment to tell you you’re wonderful

Wow… what a pretty cheeky comment. Using this logic there is a very good chance that a number of the technologies that you, I and most everyone use today would not current exist. Secondly, there could be several technologies that were spawned off the initial project that are now actively used. I would suggest that before you look at the rate of return (ROI) of this project that you dig a bit deeper and broaden your gaze.

There’s always one in every comment section… 🤦

Wow. Do you think they took the money with them? Every single cent was spent on Earth.

As for the science, https://googlethatforyou.com?q=science%20learnt%20from%20voyager%20probes.

Even that comment means we spent the money well. If you want to affect change, do something positive besides sitting on your duff searching the net complaining

Yes NOTHING!!!

Apart from the existence of a moon orbiting Jupiter, 10 moons and 2 rings arround Uranus, 5 moons and 4 rings arround Neptune and a dark spot on Neptune.

And of course also the development of the scientific tools needed for the mission.

But apart from that NOTHING!!!

and the beginning of where the

‘heliopause” is..

Yup. And the Voyagers are still listening.

If it wasn’t for the RTGs, they likely would keep functioning for several decades from now, thanks to their robust, advanced and discrete 1970s technology (AMSAT OSCAR 7 is as old and came back to the land of the living).

I dislike comparisons that involve cars, taxes or money, generally because that’s not my level, but..

Considering how long these instruments are working by now, they are a real tribute to humanity’s craftsmanship. They present humanity’s best, literally. They were our finest hour. Not only because of the Golden Records.

Let’s Imagine our washing machines would last 40+ years without maintenance.

The Voyager twins totally succeeded all expectations. They confirm that we can reach the skies if we want to. They prove that we can make things last.

And no, I’m no American, just an European.

Though this mission still makes proud, as a human being.

What did the Romans ever do for us?

Was going to say the same thing as [Kirby].

Thanks to R&D for this proyects, we get advancements in technologies, employment and lots of other things. I do not live in the USA, so I don’t get a say about taxes, but thanks to you guys the rest gets to enjoy technologies otherwise we couldn’t.

If YOU didn’t learn something from it is not important. If WE as mankind have, it is.

Oh. And you forgot to use the words “hard earned money”. Pay attention next time you bark.

I’ll be generous and offer you half a billion dollars over the course of 60 years (reasonable projections for Project Voyager). What would YOU spend it on?

Thanks for sharing. Need more projects like this. Exploration is good … and all the money is spent right here on Earth putting people to work and the creative technology to make it work. Win Win. Plus learning more about the final frontier is always good. We just need to develop that ‘warp and impulse’ drive systems to get where we are going quicker….

+1, less than 0.002 light years traveled in 43 years is depressingly slow on cosmic scales.

Not necessarily if you’re on board of such a vessel..

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time_dilation

Time dilation is ludicrously tiny at these speeds. You need to get up to 86% the speed of light before it even gets to a factor of 2.

“when the last little bit of plutonium in their radioisotope thermal generators decays to the point that they’re no longer able to talk to us”

It’s actually not the lack of power that’ll likely kill Voyager. I mean, yeah, but not *electrical* power, as in “spacecraft needs 200W to transmit” or something like that. The biggest problem is actually the lack of *heat*. In addition to the RTGs, the spacecraft also has radioisotope *heating units*, which keep the propellant warm enough. And of course *those* are decaying too.

So in fact the spacecraft’s electrical power requirements are going *up* over time, because it needs to burn more heat in order to keep the hydrazine non-frozen. The most likely failure mode is probably not going to be electrical power loss – it’s probably going to be the propellant freezing as they cut down the margin, preventing attitude adjustment.

If my Bluetooth headset would just work reliably from four feet …I’d be happy

Try using sat dish like these guys do :)

Luddite?

https://lettersofnote.com/2012/08/06/why-explore-space/

time for elon to create concentric spheres of RF/laser relays with massive dishes in space. maybe the innermost shell should be at the billion km mark from the sun — should help to keep data rates higher to other future missions

time for Elon to help us launch concentric shells of SDR enabled RF/laser relays centered on the sun. the nearest one could start at the 1 billion km mark. this should also help to improve data rates for future far flung space missions and stop ease the stain on the earth bound DSN.

Not ambitious enough.

Starship could launch a Voyager 3 with 100.000 kg of extra ion thruster stages. That should be able to catch up with Voyager 2.

“The cost of the Voyager 1 and 2 missions — including launch, mission operations from launch through the Neptune encounter and the spacecraft’s nuclear batteries (provided by the Department of Energy) — is $865 million.”

Now what could we have spent that on here on Earth? Running the DoD for about 10 minutes?

Yeah let’s pay some losers to have 10 kids instead. Much better use of our money.

Go back to Portland.

In the future they will get a response…….”I’m sorry the user is outside of the calling area….for information on roaming charges please contact your provider…. thank you for using UT&T” …(Universe Telephone and Telegraph). 😁

Hopefully Musk would just launch few more sats, this time around galactic core.

This was just announced on on Nov 14:

A main cable that supports the Arecibo Observatory broke last Friday at 7:39 p.m. Puerto Rico time.

Unlike the auxiliary cable that failed at the same facility on August 10, 2020, this main cable did not slip out of its socket. It broke and fell onto the reflector dish below, causing additional damage to the dish and other nearby cables. Both cables were connected to the same support tower. No one was hurt, and engineers are already working to determine the best way to stabilize the structure.

I think we’ve just found a certain soon-to-be-ex-president’s HaD account.

I quote Monty Python:

“The Romans are all bastards,

they have bled us ’till we’re white,

they’ve taken everything we’ve got

as if it was their right,

and we’ve got nothing in return

though they make so much fuss,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

What have the Romans,

what have the Romans,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

The aqueduct.

What?

…they, they gave us the aqueduct…

Yes, they did give us that, that’s true

And sanitation Yes, that too

The aqueduct I’ll grant is one

thing the Romans may have done

And the roads, now they’re all new

And the great wines too

Well, apart from the wines and fermentation,

And the canals for navigation

Public health for all the nation

Apart from those, which are a plus,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

What have the Romans,

what have the Romans,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

The baths.

What?

…the public baths…

Oh, yes, yes…

The public baths are a great delight,

and it’s safe to walk in the streets at night.

Cheese and medicine, irrigation,

Roman law and education

the circus for our delectation

and the gladiation

Well, apart from medicine, irrigation,

health, roads, cheese and education,

baths and the Circus Maximus,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

What have the Romans,

what have the Romans,

what have the Romans ever done for us?

Brought peace.

Oh, shut up!”

I had a tour of the Haystack Hill observatory back in the 90s (120 ft dish). Is it ever used for DSN work? I vaguely recall them explaining how they combined signals with other dishes around the world, and tiny earth plate shifts were noticeable / measurable.