Once upon a time, bailing out of a plane involved popping open the roof or door, and hopping out with your parachute, hoping that you’d maintained enough altitude to slow down before you hit the ground. As flying speeds increased and aircraft designs changed, such escape became largely impossible.

Ejector seats were the solution to this problem, with the first models entering service in the late 1940s. Around this time, the United Kingdom began development of a new fleet of bombers, intended to deliver its nuclear deterrent threat over the coming decades. The Vickers Valiant, the Handley Page Victor, and the Avro Vulcan were all selected to make up the force, entering service in 1955 through 1957 respectively. Each bomber featured ejector seats for the pilot and co-pilot, who sat at the front of the aircraft. The remaining three crew members who sat further back in the fuselage were provided with an escape hatch in the rear section of the aircraft with which to bail out in the event of an emergency.

A Fateful Decision

The decision was not a controversial one at the time of design of the V-bombers, with original plans for a jettisionable crew capsule abandoned prior to building the prototype aircraft. However, the issue was brought into sharp focus almost immediately after the Vulcan entered service. Avro Vulcan B.1 XA897 was returning from a tour of Australia and New Zealand, intending to land at Heathrow on 1 October 1956. On the day, torrential rain meant visibility was poor, and pilot Donald Howard decided to attempt a ground controlled approach to the runway.

After being advised the plane was coming in too high above the required glide path, Howard overcorrected, with the Vulcan striking the ground, tearing off the landing gear. With the plane still airborne, Howard found the controls non-responsive, gave the order to abandon the plane, and ejected successfully. Co-pilot Air Marshall Harry Broadhurst also tried the controls, and followed seconds later. With the low altitude of the accident and the forces involved, the rest of the crew went down with the plane and died on impact.

The official inquiry into the incident apportioned blame in parts to both the pilot for not aborting the landing earlier, and the ground controller for failing to update the aircrew that they had descended too low. Notably, when delivering the report to the House of Commons, Secretary of State for Air, Nigel Birch delivered a statement regarding the choice of the pilot and co-pilot to eject from the aircraft.

It would be unjust to the pilot and co-pilot were I not to make it clear, in conclusion that it was their duty to eject when they did. I am satisfied that there could have been no hope of controlling the aircraft after the initial impact. In these circumstances, it was the duty of the captain to give the order to abandon the aircraft and of all those who were on board to obey it if they were able to do so. Both the pilot and co-pilot realised when they gave their orders that, owing to the low altitude, the other occupants had no chance of escape, and they considered that their own chances were negligible.

Further Tragedy

The issue quickly became a cause célèbre for the Daily Express, which began to publicly question why three out of five crew members weren’t provided with equal means of escape. Rather than fading away, the issue remained a continual focus as further accidents stacked up. 1956 saw a Vickers Valiant lose control due to an electrical fault, with the pilot attempting to keep the aircraft aloft long enough for the crew members to escape. The co-pilot ejected safely, while the navigator made it out but died due to the plane being too low for the parachute to open. The pilot did not eject, and passed away with the rest of the crew when the plane exploded post-impact. 1958 saw another Vulcan crash with a loss of all hands, and 1959 saw a Victor go down also with a total loss of life.

Britain was home to Martin-Baker Ltd, a company founded by James Martin and Captain Valentine Baker, that originally manufactured aircraft. After Baker perished in a testing accident, Martin shifted the company’s efforts to safety equipment for aircraft. Having long lobbied the manufacturers of the V-bomber fleet to include ejector seats for all crew members, it took four years before Martin could secure an example for testing. After convincing the RAF that ejecting from the rear of the aircraft could be done, a live test was arranged for the 1 July 1960. At 1000 feet, civilian tester W T Hay ejected safely from Vickers Valiant WP199 in front of the gathered RAF officials. Unfortunately, despite the success, the Air Ministry declined to undertake modifications to the V-bomber fleet, citing issues of cost and need to keep a sufficient number of aircraft on frontline duties.

The issues were not to disappear, however. The early 1960s brought the development of surface-to-air missiles capable of striking the high-altitude V-bombers, necessitating a switch to low-altitude bombing runs in practice if crews were to evade attack. This increased the likelihood of accidents or emergencies occurring at altitudes too low for rear crew members to bail out safely. The incidents kept coming, too, with a Victor crash in 1962 claiming the lives of another two servicemen, and a Vulcan crash in 1964 leading to the deaths of all three rear crewmembers. While the Valiant was withdrawn due to structural fatigue issues in 1965, but the Vulcan and Victor continued to serve.

A Struggle of Concept Versus Reality

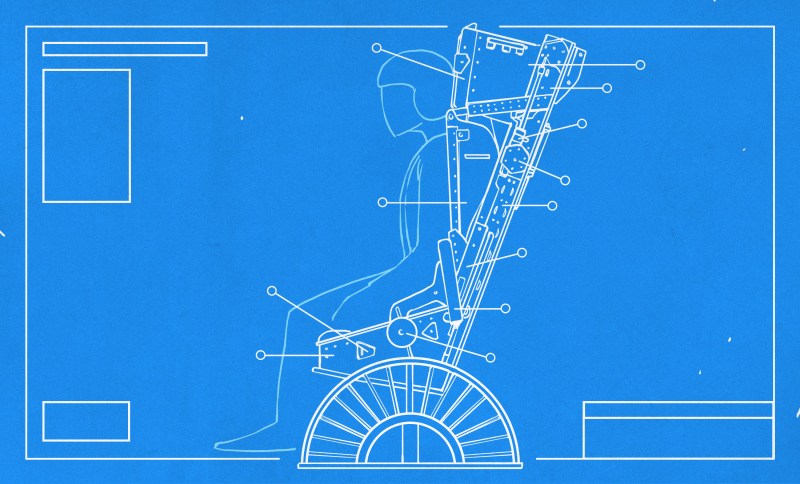

Further design work by the Martin-Baker company led to a system that allowed all three rear crew members to eject through a hole only big enough for one seat. This was achieved through a clever mechanism that fired the center seat first, before tilting the outer seats inward to fire through the same hole. However, it came to nought, with only a minor upgrade ever being implemented to the rear cabin. Seats were installed that could swivel in place, facing the crew members towards the escape hatch, and fitted with an inflatable cushion to raise the crew to a standing position for exit. The solution was implemented after testing by the Royal Aircraft Establishment had determined that escape from the rear compartment was practically impossible under even mild G loads that could be experienced in flight.

In the end, despite much hard work and demonstrated solutions, successive governments declined to have the fleet upgraded with ejection seats for all crewmembers. Citing at different times costs, complexity, or logistical issues, the wholesale retrofit of the hardware was left in the too-hard basket. The V-bombers ended up serving long past their planned obsolence of 1970, with the Vulcan retired from its conventional strike duties in 1982, while the Victor ended its days serving as a tanker in the Gulf War before leaving the flight line in 1993.

One can imagine that the many crews that flew these aircraft might have appreciated a little more forethought from the original designers, or even an investment in a retrofit when the engineering problems had been solved by private industry. Fundamentally, the controversy would not have been so serious had there been no ejector seats at all; the decision to provide them to only the front crew was the cause of such consternation. Thus, many pilots and co-pilots were faced with the gut-wrenching decision over whether to eject, or to go down fighting to the last to save one’s brothers in arms. Regardless of the reasoning behind the decisions over the years, it remains cold comfort to those that sadly didn’t make it back from the flightline.

“The issue quickly became a cause célèbre for the Daily Express, which began to publicly question why three out of five crew members weren’t provided with equal means of escape. ”

I’m reminded of a Titanic lifeboats debate I had with someone.

It was also kind of a thing in cars for a couple of decades, how come the front passengers get belts but the rear passengers are free to fly through the windshield (possibly breaking necks on the way)

Not to mention hurting or even killing the folks of high enough status to deserve the seatbelt on the way past!

That one never made sense to me, but like all cost cutting measures, its done to whatever level is socially acceptable/expected at the time – or just marginally better than the competitors so yours sells better…

Also have to point out that a military craft follows vastly different rules – when the chances of getting pulped by a missile, peppered by high calibre bullets or giant shotgun cartridges not only exists but is pretty high the design priority has to be highly functional, and if at all possible lowering that chance of taking the big hits – which keeps the crew safer than making the craft less functional. Also if you take up lots of space for safety features in the case of something like a helicopter troop carrier, you’d end up needing ten times more craft to do the job – thus actually putting more lives in jeopardy, and increasing the chance one of them will take a hit.

Cars often only had front seat occupants. But a responsible family man bought a Volvo, which had seatbelts in the back.

Ostracus, rmemembering the Vulcan in one of the James Bond movies where nuke was stolen. And it was found because sharks were circling it as because of the camo, couldn’t be seen from the air.

Also the shuttles, ejections seats not feasible, cumbersome and weighty, eh?

Mach speed ejection.

http://www.christopherjlynch.com/ejection-at-mach-105.html

Well, in the two hull-loss incidents recorded with the shuttle, I don’t think ejection seats would have helped.

The earlier concepts of the detachable crew module might have though.

The Shuttle crew cabins were only connected at a few points. Explosive disconnects at those points and around pipes, wires, etc along with explosive cord under the skin, similar to what’s embedded in the top canopy panels of some jet fighters, would have allowed for emergency separation of the crew cabin. A big parachute and flotation bags to keep the cabin afloat long enough for the crew to get out would also have been needed.

Challenger’s crew cabin did separate due to the destruction of the rest of the Shuttle, but how intact was it as it fell to the ocean? It smashed apart on impact.

So if it had had a parachute package, that was one more chance in hell than none.

The first Shuttle, Columbia, had ejection seats for the commander and pilot but no other crew members. When the first flight with more than two crew members happened, they were disabled at the request of the commander and removed a few flights later.

Actually the Space Shuttle originally was designed with an escape module for the crew. NASA deleted it from the plans because too expensive.

one problem with the titanic was the noob crew. they just didn’t have the experience to make the most out of the rescue equipment they had available. boats were launched half full and a few were destroyed. they could have saved a lot more, probably not all, with better training. of course that’s not a pass for the designers.

Except the Titanic didn’t have enough lifeboat seats to cover anywhere near the ships capacity.

“Notoriously,Titanic did not have enough lifeboats to evacuate everyone on board. She only had enough lifeboats to take about a third of the ship’s total capacity. Had every lifeboat been filled, they could only have evacuated about 53 per cent of those actually on board on the night of her sinking” – https://titanicdatabase.fandom.com/

If the ocean liners sailed in pairs, the other ship could had saved the passengers and the crew.

This might be a good resource on the Titanic and an explanation about why the lifeboat situation was what it was: https://youtu.be/bfk0tyxmdyQ

Titanic lacked enough lifeboats for her entire complement of souls because of capitalism. One shouldn’t need a video to figure that out.

Of course, I agree with you. I meant the video to show a bit more nuance, how there was the expectation that the lifeboats would be used to ferry people between the Titanic and a rescue ship (video explains why that didn’t go to plan, mainly due to issues with radio operators being jerks). This also explains why the boats weren’t fully loaded, since the crew thought the lifeboats could make multiple trips.

So yes, capitalism (see the Marconi company crap that had to be dealt with).

History of NASA G force testing and advocate for seat belts.

https://youtu.be/Ow50TBiytiE?t=59

The B-52G and H models provided ejection seats for everyone, but since the lower deck seats shot downward, those two crew members were equally screwed during low-level missions.

Lockheed’s F104 had a similar issue.

Due to its large T-tail, the ejection seat initially fired downwards. This was an unfortunate design choice as the plane had high wing loading and very sensitive controls at lower speeds, which meant many, many of them got into trouble when landing.

So… right when you needed to get away from both the airplane and the ground the most, you were riding an ejection seat that shot you smack in the center of the sandwich.

And the Harrier had a tendency to roll during takeoff or landing, ejecting the pilot at unrecoverable angles and altitudes.

We had an unlocked F-4E wing fold during takeoff at Clark Air base in 1986. The back seater ejected safely, but the pilot was killed because the aircraft rotated too far by the time his seat fired.

Nobody wants to be at the center of the sandwich (No Way!)

IIRC, if the tail gunner was still functional, the enlisted puke had to crawl back down the tunnel to get out

Violence doesn’t solve anything.

How else does one make scrambled eggs?

The B-58 Hustler and the F-111 Aardvark both implemented crew escape pods. So it’s not like it was never put into actual builds. The B-1A (six crew) tried it but the concept was dropped for ejection seats in the B-1B as more practical for the reduced to four crew.

Avro engineers have a long time experience in bad emergency exit design : the Lancaster had escape hatches too narrow for the crew to go thru with full gear and parachute – they did not change that design during the whole wwii. At the same time the B-17 had larger hatches and a much higher crew survival rate.

That said, maybe those engineers when designing the Vulvan / Handley Page Victor made it so ugly that nobody would think it was an airplane… ;)

I prefer the crew safety equipment for ICBMs – underground bunkers.

And, while the V series may be ugly, they have a charm that few aircraft can match.

Not so much for ICBM crews. There was a fair chance you’d survive in the 60’s/70’s, but with the much reduced CEP of later missiles, there’s a very good chance you’re just going to end up buried underground. Unless you launch on warning then see how far you can get away in the ~25 minutes until the warheads start arriving. And then you’re stuck on the surface with everyone else who survived.

That may have been the thinking about the V bombers as well. If they carried out the mission they were designed for, dropping thermonuclear bombs on the Soviet Union, then there was effectively no chance of them having a home base to come back from, as the entire UK would have been bombed as well.

Instead they planned to land in a friendly that might still have been safe, exactly where is still classified, but probably India was on the list.

Ah, come on, the Vulcan is cool!

It looks like an ornithopter straight outta Frank Herbert’s “Dune”.

Well he did have a bit of a thing for describing Alien craft as being exactly the same as other earth aircraft.

Seems foolish to me, the most important part of an airplane is the crew, and while you can make the most complex airplane in the world in six months, it takes at least 18 years make a pilot, protect your resources.

well they did protect the pilot and co-pilot, the navigator, flight engineer and weapon officer obviously being considered expendable

I think also you have to put yourself in the attitude of the time. V-Bombers were designed to penetrate highly defended air-space and drop gravity nuclear devices onto their targets. The assumption was that the enemy would be doing the same to your country and therefore it was pretty well considered a one way mission, so crew survivability was never high on the agenda.

However the mission profile later changed, moving from high level to low level and nuclear to conventional, however retrofitting escape systems was always going to be a challenge

I have been in a Vulcan cockpit (we have a static one only a mile up the road). Despite the size of the plane from the outside, the crew compartment is actually small. A B-52 it is not, meaning fitting extra ejection seats would always be difficult

“The assumption was that the enemy would be doing the same to your country and therefore it was pretty well considered a one way mission, so crew survivability was never high on the agenda”

And technical malfunction or accident never happen in peace time, so why bother.

There are missions “this thing was made for”, but during most of its life it will fly two way missions …

You can’t compromise and sacrifice common sense and usability to a primary goal – it has to be built atop them. Else, the thing won’t live to be there to fulfill it.

https://youtu.be/PY8zxRjOuak

I wonder if an additional, independent propulsion/control system could be integrated into a plane’s design as part of the “oh sh!t” routine – something that, when activated, changes the pitch of the plane to approach a stall condition. This would translate existing forward momentum into low speed + altitude gains. When the plane is about to stall, there would be a small window of time that would be very optimal for jettision – even if the only options were through a regular old escape hatch the crews had to crawl out of.

Of course that would be easier said than done. By definition, if the pilots/crew are needing to ditch their plane while in the air, the plane is not able to be controlled, and that could be because of a million different unpredictable causes. So while it might be impossible to ask any emergency system to control a plane that its own crew cant control, there might be some middle ground. I’m picturing something involving thrust vectoring – a rocket jet with its own independent fuel source could be mounted at a fixed angle, such that when activated it will continuously increase the pitch angle of the plane, until the pitch and and velocity sensor detects that the plane is approaching a stall angle, at which point ejector seats eject and/or escape hatches fly open and the crew can depart a slower moving, lower g-force, higher altitude plane.

“Jolly good plan, major! You’ll be a test pilot for it!”

I mean… being ejected from a fighter plane mid-flight wasn’t previously on my bucket list… but now that we’re talking about it – if a group has a perfectly good airplane they’re willing to let me eject from over some remote uninhabited desert, I’m down! Hopefully I would get to see the plane meet the ground in a fiery explosion from a nice overhead view as float on down in parachute. Less ideal would be seeing the explosion from immediately outside the plane as the ejector seat gets caught on the windshield frame and I’m there flapping around like a plastic bag stuck on a car antenna, unable to get back inside / control the plane.

I got my private pilots license back when I was 22 (now expired due to not having the time to stay current). I’m honestly surprised that my young snarky self didnt ask my instructor eye-roll inducing questions such as “so in which situations do you jettision the aircraft” or “which button is the ejector seat- I want to make sure I dont accidentally press that” (on a Cesna 172 haha).

I think the scene you want is in movie “The Right Stuff” just sit real close to the screen….

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LQt579381OI

You should easily be able to get a Sport Pilot license. That limits you to two person, single engine, unpressurized, with maximum aircraft weight, altitude, and speed limits. But you don’t have to pass a physical. If you can get a license to drive a car you should be able to get a Sport Pilot license.

At least you did not try it in a 150, instead of the 172…eyes rolling…

In some ways this is how modern ejection seats work. They have one rocket to get the seat clear of the aircraft, and additional ones to try and push it away from the ground and to a safe height for the parachute to work.

You can just about see it happening in this clip:https://youtu.be/v8spBgCo43Q?t=101 First the seat comes out of the aircraft, almost horizontal to the ground, then it goes upwards as the seat tries to get as much altitude as possible. It’s hard to see as it only takes a couple of frames, but then there’s only a handful of seconds between the pilot pulling the eject handle, and landing safely under the parachute.

The trouble with attaching emergency rockets to the whole aircraft is, as you mention, the aircraft is almost certainly not in a working condition when an emergency happens. By restricting the emergency rockets to the seat, it doesn’t matter too much what state the rest of the aircraft is in. And if the seat is damaged, there a good chance that the squishy human in it is as well.

I understood it to not be a rocket but a mortar round less projectile

My grandfather met a fellow through the flyin club he works at who had to punch out- and was subsequently grounded for a year, maybe two or three. Our best guess is the risk of spinal damage from the hard impact through the seat.

Buddy barely got back in the air when he had to eject on a different aircraft. Memory says it was his requalification flight, not honestly sure on that. Don’t think he bothers with the fast boys anymore.

True of many of the early seats – the T33 trainer I rode in 1973 was so equipped. Before the ride, you were briefed on what posture to assume to minimize the likelihood of back fractures. And I was assigned the rear seat unlike most cases as i have long legs and, if ejected from the front seat, I’d have lost them to the front windshield structure.

Later, working for Versatron Corp. who made the pintle motors for ejection seats, it was evident how zero-zero seats work. “Zero-zero” seats could safely recover from zero altitude and zero airspeed due to the vectorable thrust and gyro controls for same. Today’s designs are far more capable still!

My brother, who was an F15 crew chief for years in England, did mention that a common saying was “Meet your Maker on a Martin-Baker”…

“designing the Vulvan”

I wonder what they based the design on.

Great. Now I can’t un-see it.

I like the drawing. Remind me of my days with AutoSketch 2.0 on DOS! :)

“I wonder if an additional, independent propulsion/control system could be integrated into a plane’s design as part of the “oh sh!t” routine – something that, when activated, changes the pitch of the plane to approach a stall condition. This would translate existing forward momentum into low speed + altitude gains. When the plane is about to stall, there would be a small window of time that would be very optimal for jettision – even if the only options were through a regular old escape hatch the crews had to crawl out of.”

Hmm.

Great unless you are anything other than the right way up.

My father flew the Victor while it was in service with the RAF. He states that the pilots were given no guidance on making the decision to eject, or stay with the aircraft.

In the situation of left landing gear won’t lock, pilots might either A) land it perfectly balanced on the right gear until the speed gets too low and then scrape the left wingtip or B) cartwheel it into the nearest housing development. So those suspecting they might be category B are encouraged to point it out to sea and punch out.

This happens when your crew lacks a cartoonist.

The last sufficiently amazing cartoonist had already retired by then.

The vulnerability of the three “back seat” aircrew (Navigator Plotter, Navigator Radar and Air Electronics Officer) were no worse than those in the Lancaster, Halifax and Stirling a few years earlier. Statistics showed that only one in seven aircrew ever escaped one of these being shot down by AA or night fighter, the same odds, as it happened, for finishing a 30-operations tour. Only the pilot wore a parachute (he sat on it), the others having to unhook theirs from the fuselage wall and clip it to their harness, then open the escape door, which was often jammed by damage, and jump. Most of the time this was impossible because of fire and/or wild gyrations of the aircraft caused by battle damage, the “g” forces usually pinning them to the wall, floor or ceiling. There was an escape hatch in the floor of the bomb-aimer’s position, and a small hatch over the pilot’s head. Almost no pilots ever used it to escape, sometimes because of the same “g” forces but usually because they stayed at the controls in a desperate attempt to give the rest of the crew a chance; usually they ended up riding the crippled bomber in. The rear gunner had the least chance of all of bailing out, because he had to rotate his turret by hand-cranking it if the hydraulic power was out, which it usually was, open the rear turret doors, get his ‘chute off the wall, clip it on and jump. My wife’s cousin Ron Eeles was one of the lucky ones; he and the mid-upper gunner were the only two to bail out of a Lancaster hit by AA fire. You can read his account by entering this in the subject line: My recollections of a night bombing raid on Mailly le Camp on Wednesday 3rd May 1944 by Ron Eeles. (Because of this he became a POW, but later was at our wedding in 1960.)