It’s easy to imagine that once a spacecraft leaves Earth’s atmosphere and is in a stable orbit, the most dangerous phase of the mission is over. After all, that’s when we collectively close the live stream and turn our attentions back to terrestrial matters. Once the fire and fury of the launch is over with, all the excitement is done. From that point on, it’s just years of silently sailing through the vacuum of space. What’s the worst that could happen?

Unfortunately, satellite radio provider Sirius XM just received a harsh reminder that there’s still plenty that can go wrong after you’ve slipped Earth’s surly bonds. Despite a flawless launch in early December 2020 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 and a reportedly uneventful trip to its designated position in geostationary orbit approximately 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above the planet, their brand new SXM-7 broadcasting satellite appears to be in serious trouble.

Unfortunately, satellite radio provider Sirius XM just received a harsh reminder that there’s still plenty that can go wrong after you’ve slipped Earth’s surly bonds. Despite a flawless launch in early December 2020 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 and a reportedly uneventful trip to its designated position in geostationary orbit approximately 35,786 km (22,236 mi) above the planet, their brand new SXM-7 broadcasting satellite appears to be in serious trouble.

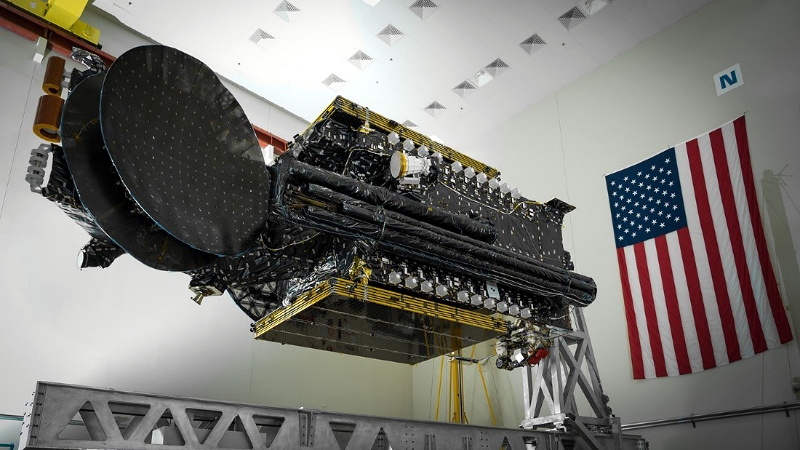

Maxar Technologies, prime contractor for the SXM-7, says they’re currently trying to determine what’s gone wrong with the 7,000 kilogram satellite. In a statement, the Colorado-based aerospace company claimed they were focused on “safely completing the commissioning of the satellite and optimizing its performance.” But the language used by Sirius XM in their January 27th filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission was notably more pessimistic. No mention is made of bringing SXM-7 online, and instead, the company makes it clear that their existing fleet of satellites will be able to maintain service to their customers until a replacement can be launched.

So what happened, and more importantly, is there any hope for SXM-7? Neither company has released any concrete details, and given the amount of money on the line, there’s a good chance the public won’t get the full story for some time. But we can theorize a bit based on what we do know, and make some predictions about where things go from here.

The Story so Far

We know the launch went off without a hitch. For one thing, Sirius XM has made it clear they aren’t implicating SpaceX in the failure. But moreover, as is customary for the commercial launch provider, the entire mission was live streamed. Had there been some kind of issue during fairing or payload separation that could have physically damaged SXM-7, the whole world would have seen it.

We also know that SXM-7 was functioning normally after it separated with the Falcon 9’s upper stage. The booster put the satellite into a geostationary transfer orbit, but it was the spacecraft’s own onboard propulsion systems that were responsible for carrying it the rest of the way. Had the satellite failed completely, or was otherwise unresponsive to ground controllers, it would never have arrived at its intended orbit.

What about the spacecraft itself? As the name implies, SXM-7 is the seventh satellite of its type, all of which have been based on some permutation of Maxar’s modular SSL-1300 bus. This is an extremely popular platform, and since its introduction in the late 1980s, has been the basis of nearly 150 current or planned communication and weather satellites. Of these, only a handful have experienced major system failures. In short, this is a mature and well-understood spacecraft. A systemic problem, while not impossible, seems unlikely.

Dead on Arrival

Shortly after liftoff, Sirius XM put out a press release announcing SXM-7 was safely in orbit and operating normally. It then started on the two week journey to geostationary orbit, and as recently as January 14th, a post on Maxar’s blog said the spacecraft was working perfectly and would soon be entering service. But it never happened.

At this point, we can’t say for sure why SXM-7 failed so late in the game. But if ground controllers had control of the spacecraft and were able to maneuver it into orbit, it stands to reason that the fault has something to do with its ability to be used commercially.

Some have theorized that the satellite’s large unfurlable reflector, critical to its ability to deliver streaming audio to the tiny antennas used by consumer XM radio receivers, has failed to open. Or potentially the issue is in one of the satellite’s powerful radios; either SXM-7 is unable to receive the uplinked audio broadcast from Sirius XM, or it can’t transmit it back down to Earth.

On January 27th a company spokesperson made it clear that despite the failure, Sirius XM still has control over the satellite and can maneuver it. This is actually a very important detail. For one thing, it confirms this wasn’t a total failure and that the spacecraft is still intact. But it also means the satellite will be able to move itself into a “graveyard orbit” if it can’t be brought online. With only a limited number of geosynchronous orbits available, non-functional satellites must be removed in a timely manner. While the ability to reposition dead communications satellites by a recovery vehicle has recently been demonstrated, it’s an expensive and complex operation that should be avoided if at all possible.

A Covered Loss

While the failure of SXM-7 is surely a great disappointment to Sirius XM, the company’s pragmatic approach to operating their satellite fleet should keep it from becoming anything more than a temporary setback. Their primary XM-3 and XM-4 satellites are still in good health, and an orbital backup is ready to take over should the need arise. Another satellite, SXM-8, is also due to join the fleet later this year. But beyond these practical considerations, the company was also careful to protect themselves financially.

In the SEC filing, Sirius XM revealed they purchased a $225 million insurance policy for SXM-7 that covered not only the launch, but the first year of commercial operation. While for many missions it would be enough to get reimbursed for a vehicle that’s destroyed during liftoff, this case is a perfect example of why extending that coverage into the spacecraft’s operational lifetime can be important when the long-term success of a commercial venture is potentially on the line.

But while that potential insurance payout might be good news for Sirius XM stockholders in the short term, it will ultimately add to an industry-wide problem that’s been building for years. With a relatively limited pool of policyholders from which premiums can be collected, insuring spacecraft is an unusually risky proposition. For example, the $410+ million payout that resulted from the loss of a United Arab Emirates military satellite in July 2019 cancelled out the year’s premiums for the entire industry.

Traditionally this hasn’t been much of a concern, but as launches become cheaper and more frequent, the likelihood that insurers will get hit with a claim increases. Logically this should lead to rising premiums, but since spacecraft insurance isn’t compulsory, insurers could price themselves right out the market if they aren’t careful. It will be interesting to see if an influx of new customers can balance out the equation in the coming decades, or if the concept of space insurance in its current form ends up being little more than an interesting historical footnote from the fledgling days of space commerce.

Funny when you put it like that. Pricing yourself out of a market, if you’ll loose money in it, sounds like exactly what one should do.

How do you “Loose” money?

You run it thru Congress. Fast and loose with ourxxxmy grandkids’ money.

Lots of satellites explode, and you pay out more than the premiums you collected.

Lots of satellites don’t explode, and the premiums you collect cover the payouts you have to make on the rest. If your actuaries did their job, you stay in business as an insurer. If not, your actuarial mistakes bankrupt your company.

If you can lose your ability to spell, you can loose anything ;)

Aliens did it.

SImpsons did it. 1999 “Brother’s little helper” Bart shoots down a satellite.

Have they tried turning it off and back on again?

Heck with that. Percussive maintenance FTW — give it a whack!

Maybe they should jiggle the handle

Wouldn’t have happened if they used Linux…

Yeah, it would have exploded on the launchpad instead. Running Linux is not the solution to every technical problem.

Right, a 555 would even be better. Keep it simple and stupid.

Right, huge capacitor, big resistor, activating a relay, automatically power cycle the sucker once a month, software bug independent. :-D

A 555 IS USED WAY to often when a cap and resistor with one transistor will do the job.

A Russian astronaut knows how to fix it.

A few taps .. and voala

Heh, skip to 28 secs if impatient…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dEkOT3IngMQ

man, that Swedish guy gets all the Russian parts nowadays….

Heh, I’m always confusing him with the guy that played Balki in the Perfect Strangers sitcom.

7 tons? Hmmm. Switch on vacuum tube heaters.

it needs so maneuvering capability to stay in the desired orbit…most of the weight are probably the rocket bits, fuel for them and the superstructure keeping them together…

If space is a vacuum, would a vacuum tube need to be vacuumed?

Very good question. Probably not, AFAICT.

I wonder if the lack of gravity might affect arcs and whatnot. Vacuum tubes were designed on earth. Does a vacuum surrounded by atmosphere while contained in glass act differently than a “tube” exposed to unlimited vacuum?

Cosmic radiation is a whole other story.

they can be used in any orientation.

You’re probably joking, but traveling-wave tube amplifiers are still widely used in spacecraft radio transmitters. It’s one of the last widespread kinds of vacuum tube. Here’s an article from 2015 on recent and in-progress developments to improve efficiency and longevity: https://spectrum.ieee.org/semiconductors/devices/the-quest-for-the-ultimate-vacuum-tube

Ok, I give. What is that museum piece in the top of article photo?

As a rough guess, maybe it’s the SXM-7

The same image appears on SiriusXM’s blog about the launch.

https://blog.siriusxm.com/sxm-7-satellite-launches-aboard-spacex-rocket

Not sure if this is some kind of joke that’s gone over my head, but that’s the SXM-7 satellite that the whole post is about.

Photo was taken pre-launch?

No, the cameraman is just really tall

That’s a good bet, since there are no warehouses in space.

I thought they took the photo after it burned up!

B^)

” While the ability to reposition dead communications satellites by a recovery vehicle has recently been demonstrated, it’s an expensive and complex operation that should be avoided if at all possible.”

ISS getting into the ifixit business. That’ll give it some life.

” Logically this should lead to rising premiums, but since spacecraft insurance isn’t compulsory, insurers could price themselves right out the market if they aren’t careful. ”

Good thing failure is optional, as well as associated losses. The market may not require it, but how many losses till people realize one can’t do without shared risk.

SXM-7 orbit – about 35,786km

ISS orbit – about 400km

it’s a wee bit out of reach for them…

Just grab an Uber to drive you the last 35,386km, duh

You mean the one Elon launched on the Falcon Heavy’s maiden flight?

I mean, Starman’s gotten 52,204,866 km on that Roadster, so it’s a possibility /s.

Would still make a much better satellite repair and reposition hub than the planet – keep a ‘shuttle’ docked to the ISS and send it out each time its needed – only need to lift the spacecraft out of the atmosphere once, the parts and fuel it will use just add a small amount to the ISS’s existing resupply requirements. The ISS’s own orbit means it will end up in pretty good launch positions for all satellites at some point – its going round much faster than they are (anything lower than the ISS isn’t going to be repaired, its just going to burn).

All that is needed is the space shuttle like craft up there (doesn’t need the heatshield and wings, unless it’s meant to come back down. Just the large internal space to make working on satellites easier) and to send up some resupply pods with fuel for it (maybe satellites too) and materials to repair the dead birds.

hopefully you can automate the entire process, or at minimum do it via ROV, life support being heavy after all, plus the need to place a satellite inside anything is debatable, it could be a one use vehicle that limpets onto a satellite to act as maneuver jets,

That exists. Northrop Grumman MEV, recently used for the first time, as mentioned in the article with a link to another Hackaday post about it.

it is however much cheaper to boost from the ISS than from Earth, so while the ISS isn’t the platform for it, in theory a base with drones to do satellite refuel/repair isn’t that insane, especially if you can source fuel in orbit (hello big icy rocks, or the moon for water to crack)

Well if they can’t get it to work for 365 days – then maybe they should try it for 54.95 days and if that doesn’t work -then maybe they could get it to work for 5.95 days a months for 6 months and if that works then maybe it will go out of promotion and will work for 19.95 days a month for the 1st year.

I think you should cancel this comment and you might be offered a better deal.

Insurance is all about math;

Price = Risk * Value.

The big issue I think is the very small market (number of launches), as there is not much room for competition or even bad luck.

The other the very large value difference from one sat to another, since, it may be as low as a few million dollars, up past to the 400 million that was mentioned.

Try control alt delete

Ahh. The last comprehensible MS OS!

“Hey, shouldn’t this Arduino be in the satellite?”

Unplug

Count to 30

Plug it back in

Power on

Forced Windows Update bricked it. Need to plug in the USB recovery stick. … Ooops. Put the USB stick on the Space Shuttle and do a space walk. … Doh!

Thank goodness Sirius XM is owned by “Liberty Mutual”

When did they get policy?

2/3rds of subscribers are freebies in new cars, then the incentive for subscribers who want to cancel Sirius offers

6mos for 6 dollors

Traditionally this hasn’t been much of a concern, but as launches become cheaper and more frequent, the likelihood that insurers will get hit with a claim increases. Logically this should lead to rising premiums….

Uh, no. If anything it may lead to lower premiums. In fire insurance, the odds of a single house burning down are low. Insurers pay out every day for this. The premium is low because in a given year the number of houses that burn down is pretty consistent. This leads to a well known cost which leads to consistent premiums. The same would happen for satellite launches. Insurers will get hit with claims, but they will also have more launches to collect premiums from as well to offset the losses. Once the number of launch failures goes from a random number to a consistent number in a year the risk will be well understood and the costs will similarly be understood & limited.

As well, technology will continue to advance, driving down failures.

Except that’s literally the opposite of what’s happening. The premiums aren’t high enough to sustain the market, and there’s no way to predict how many claims a year there will be. Did you even read the linked Reuters article?

XM has history of issues with their satellites and the insurance that covers them. Not long after XM1 and XM2 were put into service the manufacture informed XM that an issue was discovered that limited the power of the satellites. XM thought they were covered but the insurance company bulked at paying for two failures, they argued the coverage was for both satellites but only it either one failed and not if the same problem was encountered with both satellites. A lawsuit happened, a settlement was reached, but it was messy. In the end both satellites were in service until 2016 when they were deactivated and put into graveyard orbits.

Update Failed! WiFi connection not available.

Since when has an insurance company lost money? In the event of a claim they simply amortise it over a few years and suffer minimal financial pain.