Closed captioning on television and subtitles on DVD, Blu-ray, and streaming media are taken for granted today. But it wasn’t always so. In fact, it was quite a struggle for captioning to become commonplace. Back in the early 2000s, I unexpectedly found myself involved in a variety of closed captioning projects, both designing hardware and consulting with engineering teams at various consumer electronics manufacturers. I may have been the last engineer working with analog captioning as everyone else moved on to digital.

But before digging in, there is a lot of confusing and imprecise language floating around on this topic. Let’s establish some definitions. I often use the word captioning which encompasses both closed captions and subtitles:

- Closed Captions: Transmitted in a non-visible manner as textual data. Usually they can be enabled or disabled by the user. In the NTSC system, it’s often referred to as Line 21, since it was transmitted on video line number 21 in the Vertical Blanking Interval (VBI).

- Subtitles: Rendered in a graphical format and overlaid onto the video / film. Usually they cannot be turned off. Also called open or hard captions.

The text contained in captions generally falls into one of three categories. Pure dialogue (nothing more) is often the style of captioning you see in subtitles on a DVD or Blu-ray. Ordinary captioning includes the dialogue, but with the addition of occasional cues for music or a non-visible event (a doorbell ringing, for example). Finally, “Subtitles for the Deaf or Hard-of-hearing” (SDH) is a more verbose style that adds even more descriptive information about the program, including the speaker’s name, off-camera events, etc.

Roughly speaking, closed captions are targeting the deaf and hard of hearing audience. Subtitles are targeting an audience who can hear the program but want to view the dialogue for some reason, like understanding a foreign movie or learning a new language.

Titles Before Talkies

Subtitles are as old as movies themselves. Since the first movies didn’t have sound, they used what are now called intertitles to convey dialogue and expository information. These were full-screens of text inserted (not overlaid) into the film at appropriate places. Some attempts were made at overlaying the subtitles which used a second projector and glass slides of text which were manually switched out by the projectionist, hopefully in synchronization with the dialogue. One forward-thinking but overlooked inventor experimented with comic book dialogue balloons which appeared next to the actor who was speaking. These techniques also made distribution of a film to other countries a relatively painless affair — only the intertitles had to be translated.

This changed with the arrival of “talkies” in the late 1920s. Now there was no need for intertitles since you could hear the dialogue. But translations for foreign audiences were still desired, and various time-consuming optical and chemical processes were used to generate the kind of subtitles we think of today. But there were no subtitles for local audiences — no doubt to the irritation of deaf and hard-of-hearing patrons who had been equally enjoying the movies alongside hearing persons for years.

Television

As television grew in popularity, there were some attempts at optical subtitles in the early years, but these were not wildly successful nor widely adopted. In the United States, there was interest brewing in closed captioning systems by the end of the 1960s. In April 1970, the FCC received a petition asking that emergency alerts be accompanied by text for deaf viewers. This request came at a perfect point in time when the technology was ready, and the various parties were interested and prepared to take on the challenge.

It was at this time that deaf bureaucrat Malcolm Norwood from the Department of Education (then HEW) enters the story. He had been working in the Captioned Films for the Deaf department since 1960. Today he is often called the Father of Closed Captioning within the community. He was the perfect leader to champion this new technology and he accepted the challenge.

The FCC agreed in principle with the issues raised, and in response issued Public Notice 70-1328 in December 1970. Malcolm and the DOE brought together a team in 1971 which included the National Bureau of Standards, the National Association of Broadcasters, ABC, and PBS. They held a conference in Nashville (PDF) in December of 1971, which we can say was the birthplace of closed captioning.

It turns out that the technical implementation of broadcasting captions built on existing work. Over at the the National Bureau of Standards, engineer Dave Howe had been developing a system called TvTime to distribute accurate time signals over the air. This system sent a code over a video line in the VBI, using a method which eventually morphed into the CC standard. They had been testing the system with ABC, PBS, and NBC. ABC had even begun using this system to send text messages between affiliate stations.

Another system presented at the conference by HRB-Singer altered the vertical scanning of the receiver so that additional VBI lines were visible, and transmitted the caption text digitally, but visually, in those newly-exposed lines. This caused some concern among the TV set manufacturers, and thankfully the NBS system eventually won out.

After a few promising demonstrations, in 1973 PBS station WETA in the District of Columbia was authorized to broadcast closed captioned signals in order to further develop and refine the system. These efforts were successful, and in 1976 the FCC formally reserved line 21 for closed captions.

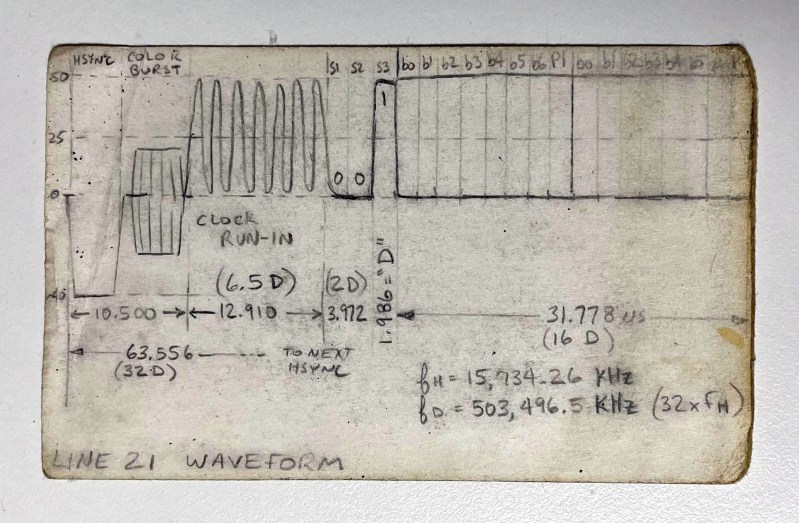

Adapting Broadcasts for Line 21

In its final form, the signal on line 21 had a few cycles of clock run-in to lock the decoder’s data recovery oscillator, followed by a 3-bit start pattern, and finally two parity-protected characters of text. The text encoding is almost always ASCII, with a few exceptions and special symbols considered necessary for the task. Text was always transmitted as pair of characters, and has traditionally been sent in all capital letters. Control codes are also byte pairs, and they perform functions like positioning the cursor, switching captioning services, changing colors, etc. Because control codes were so crucial to the proper display of text, parity protection wasn’t enough — they were usually transmitted twice, the duplicate control code pair being ignored if the first pair was error-free.

| Summary of Line 21 data | |

|---|---|

| Basic Rate | 503.496 kBd (32 x Horiz freq) |

| Grouping | 2 each 7-bit + parity bit characters / video line |

| Encoding | ASCII, with some modifications |

| Services | odd fields: CC1/CC2, T1/T2 |

| even fields: CC3/CC4, T3,T4, XDS | |

| Specification | EIA-608, 47 CFR 15.119, TeleCaption II |

Today we are accustomed to near-perfect video and audio programming, thanks to digital transmissions and wired/optical networks. Adding a few extra bytes into an existing protocol packet would barely give us pause. But back then, other factors had to be considered. The resulting CC standard was fine-tuned during lengthy and laborious field tests. The captioned video signal had to be robust when transmitted over the air. Engineers had to address and solve problems like signal strength degradation in fringe reception areas and multipath in dense urban areas.

As for the captioning methods, there were a few different types available. By far the most common styles were POP-ON and ROLL-UP. In POP-ON captioning, the receiver accumulated the incoming text in a buffer until receipt of a “flip-memory” control code, whereupon the entire caption would immediately appear on-screen simultaneously with the spoken dialogue. This style was typically used with prerecorded, scripted material such as movies and dramas. On the other hand, with ROLL-ON captioning, as its name implies, the text physically rolled-up from the bottom of the screen line-by-line. It was used for live broadcasts such as news programs and sporting events. The text naturally must be delayed from the audio due to the nature of the live speech transcription process.

The Brits Did it Differently, and Implemented Teletext in the Process

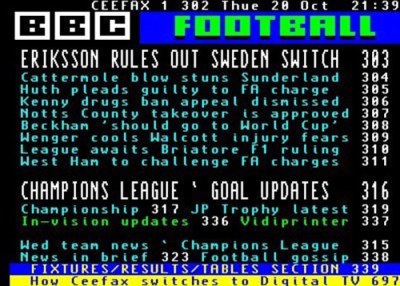

Across the pond, broadcast engineers at the BBC approached the issue from a different angle. Their managers asked if there was any way to use the transmitters to send data, since they were otherwise idle for one quarter of each day. Therefore they worked on maximizing the amount of data which could be transmitted.

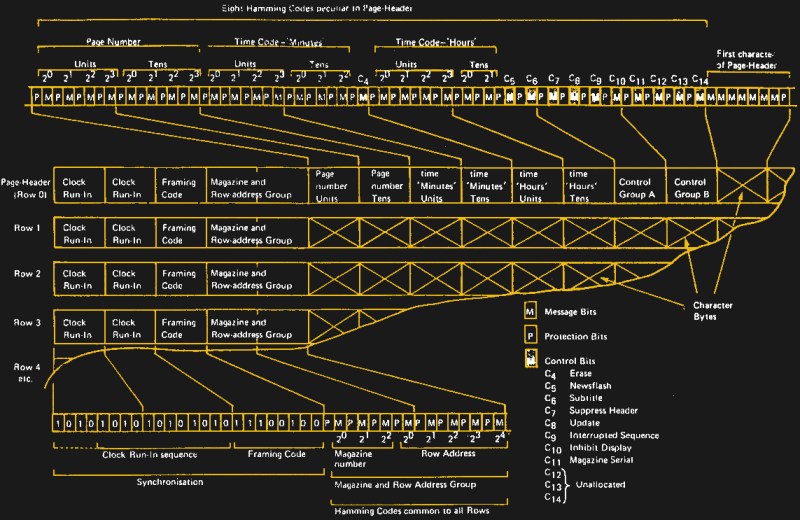

The initial service worked like a FAX machine by scanning, transmitting, and printing a newspaper page. Eventually, the BBC adopted an all-digital approach called CEEFAX developed by engineer John Adams of Philips. Simultaneously, a competing and incompatible service called ORACLE was begun by other broadcasters. In 1974, everyone finally settled on a merged standard called World System Teletext (WST) adopted as CCIR 653. Broadcasters in North America adopted a slight variant of WST called the North American Broadcast Teletext Specification (NABTS). Being a higher data rate than CC, teletext is less forgiving of transmission errors. It employs a couple of different Hamming codes to protect and optionally recover from errors in key data fields. It is quite a complex format to decode compared to line 21.

As for the format, teletext services broadcast three-digit pages of text and block graphical data — conceptually an electronic magazine. Categories of content were grouped by pages:

- 100s – News

- 200s – Business News

- 300s – Sport

- 400s – Weather and Travel

- 500s – Entertainment

- 600s – TV and Radio Listings

These text in these magazine pages are an integral part of the packet structure. For example, the text of line 4 in page 203 belongs in a specific packet for that page/line. Since the broadcaster is continuously transmitting all magazines and their pages, it may take a few seconds for the page you request to appear on-screen. NABTS takes a more free-form approach. The data can almost be considered a serial stream of text, like a connection of a terminal to a computer. If you need a new line of text, you send a CR/LF pair.

| Summary of Teletext Data | |

|---|---|

| Basic Rate | 6.938 MBd |

| Grouping | 360 bits/line, 40 available text characters |

| Encoding | Similar to Extended ASCII, with code pages |

| Services | Multiple page magazines, 40×24 chars each page |

| Specifications | Europe: WST ITU-R BT.653 (formerly CCIR 653) |

| North America: NABTS EIA-516 |

The Hacks That Made It All Work

Most of my designs were for use in North America, but I needed to learn about European teletext for a few candidate projects. In Europe, page 888 of the teletext system was designated to carry closed captioning text. This page has a transparent background and the receiver overlays it onto the video. The visual result was practically the same as in North America. But it posed some problems regarding media like VHS tapes.

The teletext signal couldn’t be recorded or played back on your typical home VHS recorder. To solve this, many tapes were made using an adaptation of the North American line 21 system, but applied to the PAL video format. This method was variously called line 22 or line 25 (the confusion being that PAL line #1 is different place than NTSC line #1), but was basically the same. A manufacturer who has a CC decoder in their NTSC product can easily adapt it to work in PAL countries.

How did I get PAL VHS tapes? I asked an engineer colleague at Philips Southampton if he could send me some sample tapes for testing. His wife bought some used from a local rental store and sent them to me. This was before the days of PayPal, so I sent her an international money order for $60. This covered the price of the tapes and shipping, plus a few extra dollars “tip” for her trouble. Some weeks later, I got an email from him saying that “you Americans sure give generous tips”. His wife had received my money order for $600, not $60! It took many months, but eventually the post office caught their mistake and she returned the overage.

In South Korea, a colleague was involved in the captioning industry back in the late 1990s. He was asked to participate on a government panel considering the nationwide adoption of closed captioning. The final result was comical — instead of CC, the committee decided to provided extremely loud external TV speakers free-of-charge to people with hearing difficulties. Fortunately, the conventional form of closed captioning has since been adopted with the advent of digital television broadcasting.

Designing on the Trailing Edge

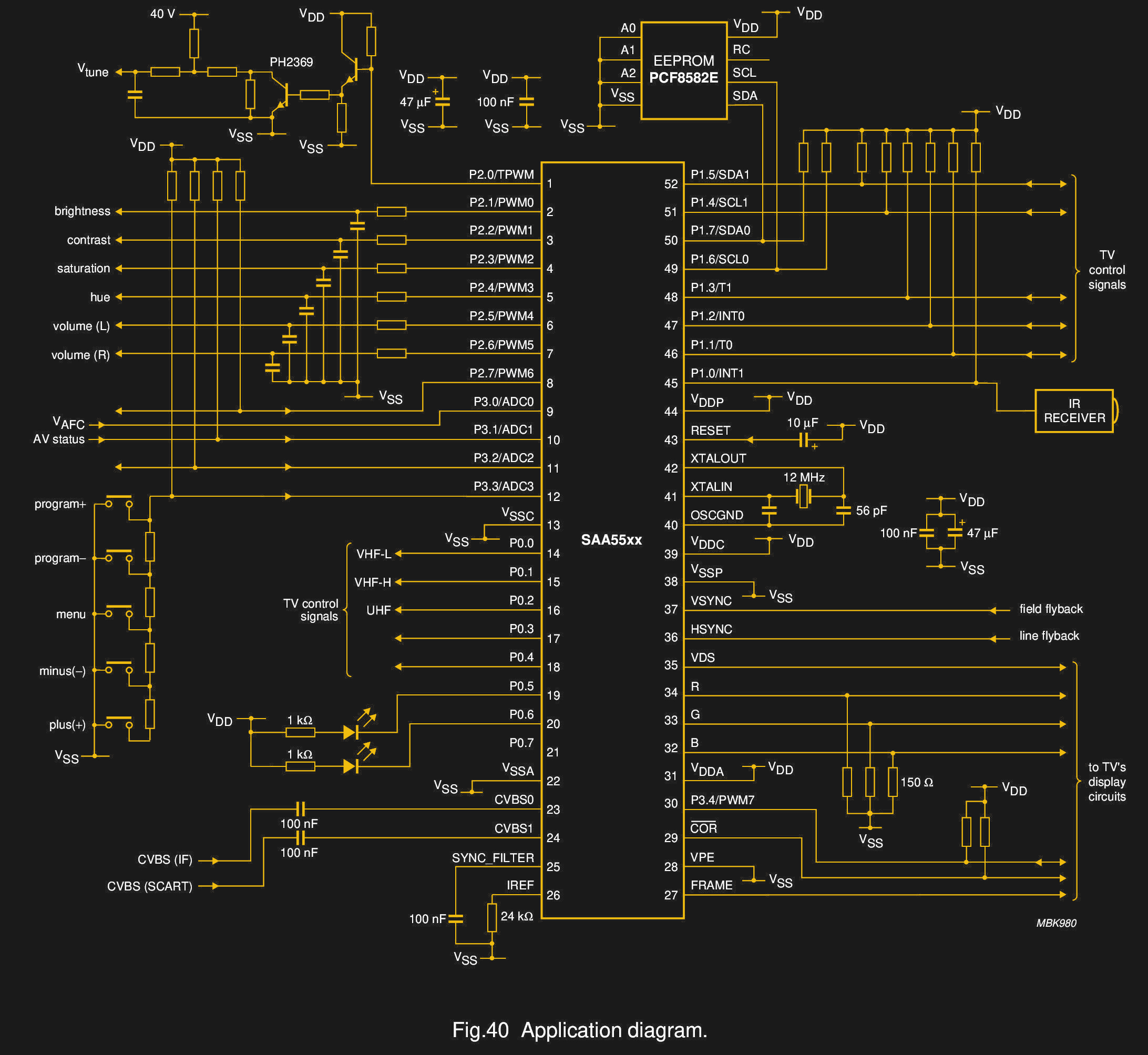

By the year 2000, almost all televisions had CC decoders built-in. As a result, there were a variety of ICs available to extract and process the line 21 signal. One example was from Philips Semiconductor (which became NXP and is now Freescale). As a key developer of teletext technology and a major chip supplier to the television industry, they offered a wide variety of CC and teletext processors. I developed several designs based on a chip from their Painter family of TV controllers. These were 8051-based microcontrollers with all the extras needed for teletext, closed captions, and user menus. They had VBI data slicers, character generators and ROM fonts, all integrated onto one die.

I still remember discovering the Painter chip buried pages deep in an internet search one day. When I couldn’t find any detailed information, I called the local rep and was told, “You aren’t supposed to even know about this part number — it’s a secret!”. Eventually the business logistics were resolved and I was allowed to use the chip. That was the only masked-ROM chip I ever made. I can still feel the rumbling in my stomach on the day I delivered the hex file to the local Philips office. The rep and I were hunched over the computer as we double- and triple-checked each entry on their internal ordering system. Once we pressed SEND, the bits were irrevocably transmitted to the factory and permanently burned into many thousands of chips. Even though we had thoroughly tested and proven the firmware in the lab, it was nevertheless a stressful day.

As I developed several other designs, it became clear that these special purpose chips should be avoided if any reasonable longevity was needed. The Painter chips were being phased out, several other options were disappearing as well. The writing was on the wall — digital broadcasting was here to stay, and the chip manufacturers were no longer making or supporting analog CC chips. I decided that future CC projects had to be done using general purpose ICs. I plan to delve into that in a future article along with unexpected applications of CC technology, the process of making captions, and how captioning made (or didn’t make) the transition to digital broadcasting and media.

Interesting history! I’ve been using closed captioning for my hearing loss since the 1980s and still have my old fake-wood sticker-covered metal captioning device. Used it until I got a new TV in 2000 with built-in captioning (all TVs in US were required to have it in 1995).

Some of the mismatches can be funny.

I had a Tele-Caption II back in the day, it was godsend for me as I was born deaf and it was hard to lip-read people on TV. When I was in high school in early 1990s, I wrote to a local representative to support caption act, the reasoning was it’d be cheaper in the long run to have one included with every TV rather than separate, be more accessible to people who can barely afford a basic TV and not afford separate caption decoder, and also be simpler to set up and use without needing to hook up separate caption decoder. Also with TV having them built in, more TV stations would be encouraged to have caption available on everything. Today, outside some boring commercial, it’s rare to find any program still running old shows or movies without caption added. AFAIK new shows and programs are required to have caption available.

I still have my first TV with built in caption, it’s sitting on a shelf in the closet. And I might still have my Tele-Caption II somewhere.

Related Vid

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6SL6zs2bDks

Upvote for princess Bride in the video’s thumbnail.

I would argue that DVD has subtitles and not captions, if we use your definition. DVD encodes the subtitles as graphics instead of text, hence the chunky lettering when ripping to modern archival systems.

Perry, good point. Most North American DVDs and some BDs contain both subtitles and closed captioning. I’ll be expanding on this in the next article.

Can you explain why until quite recently a TV could display closed captions any way you wanted, as long as it was all caps white text on a solid black bar?

I’ve noticed that newer TVs have options for font, color, outline on/off/color, background color and transparency. It’s possible to make CC off a DVD look like embedded (not part of the video image) subtitles on a Blu-Ray. It’s not like the technology to do that was suddenly developed a couple of years ago.

DVD subtitles are images with alpha channel for transparency. Blu-Ray subtitles are basically a higher resolution version. Lazy way to do it, especially when at the intro of Blu-Ray is should have been easy and inexpensive to put the subtitle rendering in the players (or player software on computers) and had simple formatted text multiplexed into the video.

I want to see a Smart TV that can properly render Advanced Sub Station subtitles. That format can have TrueType fonts multiplexed into the video and can do tricks like colors, animations, animated color, rotations, positioning subtitles anywhere on screen etc. It’s very popular with Anime subtitlers. At the other end is SRT. Simply a list of numbered entries of start and stop times, with the text to display, and basic style commands in angle brackets. No positions commands though some basic animation can be done by having a rapid series of entries for the same text with color info for each character or having a line spell out a character at a time by having each repetition with one more character. Could do a scroll by “pushing” across with an increasing number of spaces, which would break with players that treat 2+ spaces as one.

And then there’s Sony. Their Blu-Ray players, when playing videos off USB with text subtitle formats like SRT, render them with the blockiest DVD style subtitle font you’ve ever seen. Even worse, it’s not scaled to always be the same relative size to the screen. Play a 720p video and the text is larger than with a 1080p video. Could be there’s a chunk of the firmware with cheezy little bitmaps of all the characters instead of a decent vector font and scalable rendering code. Pretty garbage way of doing that on a $250 UHD player! (And it doesn’t even support Opus audio, which everyone else does.)

Oh, there’s Vizio, which doesn’t support subtitles from USB media at all, no matter what format, even if the video is DVD formatted MPEG2 with Closed Captions. Them and Sony need to get with the modern times.

Gregg — I’ll be addressing those questions in a follow-up article. It’s a complicated topic.

Looking forward to it!

Thanks!

The original analog closed captioning standard supports color, but it is hardly used. One of the major uses I ever saw of it was a music video on MTV, I can’t remember the song or artist, sometime in the 97/99 era, but every word in the captions was a different color. Really the only other time I sometimes saw color used was sometimes at the end of a show where it might say something like captioning provided by ______ and it might have been in something like yellow rather than the white of the actual show captions. The color of the captions wasn’t settable by the user, though maybe there were some TVs/decoder boxes that allowed it? but rather they were some kind of control character in the data stream to tell the decoder what color to display

Actually, DVD has both! DVDs store textual captions which are output on line 21 of a DVD player’s composite output. There is an option hidden in most DVD players’ menus to overlay them on the image so that you can use them with higher quality video outputs.

Older DVDs like early Simpsons show set still used old like 21 caption and it worked fine on older player connected via composite, or with some TV, component. (players that upscales to 720 or 1080 over component often didn’t work with caption) Newer DVD players are HDMI only (for a few years or so) and is required to have built in decoder since analog caption code can’t be sent over HDMI.

I noticed that. No menu on the DVD for captions, but composite into the tv set showed captions if I turned on captions on the tv.

And it didn’t happen after I switched to an hdmi cable.

I use closed captions and appreciate them. But, they still need some work, especially on live programs where much of the content can be dropped. Try following a news broadcast in closed captions.

Line 21 is pretty a pretty clever mod to NTSC, but then again so was colour. What can’t NTSC do? (And don’t say get the colours right!)

The American NTSC didn’t add “colour” to our TV standard, they added color. It was the Brits that added colour to PAL. ;)

NTSC was the standard in Canada, where “colour” is also acceptable.

“Philips Semiconductor (which became NXP and is now Freescale)”

Philips Semi became NXP, but NXP acquired Freescale, and is still known as NXP.

A fascinating look into closed-captioning. I came across a SAA55xx data sheet years ago and wanted to play with it, but could not find it anywhere.

Phillips had a lot of interesting chips.

The SAA5050 teletext display chip is legendary in the UK. It was used to render the teletext pages, but was also used as the video output chip in a number of computes – in particular MODE 7 on the BBC Micro (the 1980s 6502-based computer developed by Acorn – who also created the first ARM processor – in association the broadcaster, the BBC, who also helped invent teletext).

The SAA5050 did a gorgeous job of ‘character rounding’ bitmaps, really making use of the full resolution of an interlaced display without flickering. If you want to use the classic SAA5050/MODE 7 font now – it’s available as ‘Bedstead’

All of our 80s and early 90s TVs that had teletext in them had that SAA5050 font.

And yet you still had to get the additional “cheese wedge” adapter to view teletext on the BBC Micro, was still a cool bit of kit to own though!

Datasheet linked in the article, chips available for not super much on eBay… go, go, go!

I remember adjusting my TV to underscan because of the rounded corners and sides of picture tubes. I was able to see what was happening on those lines even the color burst, as well as camera framed classic movies. TBS was using teletext way back I can’t recall when, ’80’s?

The curve of glass under vacuum was the shape of the mid century. I hated it. About ’72 I repackaged a broken plastic case portable 19 inch TV where the guts separated from what little held the tube. Dangerous but working. I put it into an old wooden cabinet console. When I cut out a piece of plywood to mount the picture tube I cut out the shape most familiar to us today. Straight sides with small rounded corners like Apple did.

A few years ago, I did a ground-up implemention of the EIA-608 and CEA-708 decoders to support switching to a new SoC manufacturer for Roku TV models. We’d previously relied on a library from a vendor, but wanted to have the same code, no matter what chip we were using. That was a lot of fun, but so much of the history around the formats was buried away in FCC documents, books and a few journal articles that I could find. My favorite bug was one about supporting TOO MANY rows for pop-up captions; the TV manufacturer we were working with only wanted four rows to show up, even if we could easily show all 16.

Couple of things. In the UK – and also in other territories – the word subtitle IS used instead of Closed Captions (which is seen as a US-English term) to describe optional overlaid captions that are sent using Teletext. In the UK broadcasters used to put a ‘Subtitles’ logo up over the channel ident before a show to indicate that optional subtitles could be watched using Teletext. Closed Captions simply isn’t a term used by the public in the UK. Subtitles is the term used for both burned in captions (as we see on foreign films and TV series) and optional captions that can be enabled and disabled by the viewing audience (or on DVDs)

Also 888 is just a page currently used in the UK for subtitles, which was standardised across broadcasters (At one point in the UK the BBC and ITV used different page numbers ISTR). The teletext spec allows any page to be used for subtitles – though I think as part of the update to the spec you can signal which page is carrying subtitles for the network you are tuned to.

In some European countries the same text service was (is?) carried across multiple networks (to reduce the costs of running different services on multiple networks run by the same broadcaster) – so you had to make sure to chose the right page number for the subtitles of the network you were watching (or you could get the subtitles for the wrong network overlaid)

Also AIUI NABTS (which is I think more related to the original French Antipode system) was one system trialled/used in North America, but there was also a much more direct port of the European Teletext system (now known as WST – World Systems Teletext) that was very similar to the system originally developed by the BBC and the IBA in the UK (It ran at a lower clock & data rate, and thus had fewer characters per line to preserve the ‘text line per VBI line’ relationship that WST has)

Should also add that properly rendered teletext subtitles don’t have a transparent background – they have a black background box for the text (though you can make this another colour – which is sometimes used to signal non-dialogue stuff like ‘A Dog Barks’ or ‘Police Siren’ ) – the transparent area (where the picture appears) is carried by a separate attribute.

I’ve often wondered if the menu text chip in 1990’s CRT televisions could be repurposed into a general graphics/display chip for an 8 bit computer.

The pixel size looked decently small and the later ones could display many colors. It’s via that chip that hacks to convert a CRT into an RGB monitor for 1980’s game consoles and micro computers are accomplished. The hacks don’t use the chip, they use its interface to the rest of the TV’s video circuitry.

Oh it definitely could, supposing you could get one and the supporting tools. To use the Painter chip for example you needed the Keil tool-chain required to compile special encrypted source code files from a proprietary Philips library, a custom Hitek in-circuit emulator, and a special engineering demo flash chip programmer. Other such chips might have had easier development tools.

I quite like the idea of this, it could be interesting if one of those display chips was able to be used. Although I wonder if they are hard coded menus or whether they grab data from a separate or internal memory that can potentially be written to.

In theory you could just have a double buffer two of memory chips or better yet, extra long shift registers, then store the entire display on them and clock them at just the right speed. Fill one, while you dump the other to the display, then switch between them or loop them for static images.

It seems someone created a thing called Teefax that uses a Raspberry Pi to send ceefax data to a tv. That could be an interesting starting point.

I do wonder if the intelligence community ever made use of this technology to disseminate information. It seems likely to me from a convenience stand point that the idea would have at least been considered. Perhaps with custom receiving hardware, just being on the right ceefax page at the right time to load the data or selecting an unlisted colour on a certain page to unhide or decode some text. It makes me wonder if this sort of concept could be used by the maker community.

If a picture and sound wasn’t being transmitted, only say half the ceefax data and only for a short period, there wouldn’t be much to flag up the FCC.

Yes the data rate is low and yes it’s plain text, but there is potential.

>The teletext signal couldn’t be recorded or played back on your typical home VHS recorder.

Yes it could, and it was quite common to be able to view teletext off of a video tape that was recorded from TV and played back through the RF adapter. I personally have recorded such VHS tapes.

The main difference was whether the TV would decode the teletext data when it was coming in through the composite or component video inputs, versus the tuner circuit. All the TVs which had teletext decoding would decode it through the RF input as designed.

The VHS tape would definitely record it, and it would take quite a bad tape before it would completely vanish.

Aaaa, teletex. Was a huge thing in Italy in the 90′. You can fint al kind of information, like the latest news, sport, tv guide, ecc.

In the uk they made a working version of Worms playable whith teletext (https://www.team17.com/worms-for-teletext-the-story-behind-a-long-lost-technical-marvel/)

you looked at the date this article was published, right?

Circa 2000 I was working at Princeton Video Image on technology to allow insertion of advertising images into sports broadcasts by the home cable box. The final product would’ve inserted image coordinates into the VBI which would then be used by the cable box to insert the image. To demonstrate the cable box side this was simplified by using the CC to carry an index into a table of pre-computed values. Demonstration software for a Broadcom prototype set top box was developed and shown in the Broadcom booth at a cable show in New Orleans. The demonstration used video of a baseball game fed from a DigiBeta deck and inserted selectable advertisements on the wall behind the batter in the game video as displayed. Alas, PVI was in financial trouble so I was laid off shortly thereafter and the project never saw the light of day.

Interesting article.. I would love to see one explaining modern captioning on digital broadcasts.. and what is the difference between 608 and 708 captions

I see “63,556” on the file card. Should that be “65,536” — or “65,535”?

Some number are burned into my ROM…

You almost caught the error I was hinting at. I have the commas and decimal points wrong for the H and D frequencies written down on the card. The horizontal scan frequency is 15.73426 kHz, NOT 15,724.26 kHz! Same goes for the data frequency.

The terminology of closed captions/open captions/subtitles is an ongoing puzzle for me. Suspect from the comments here that the terms might not be standards-based but instead a matter of common usage (or marketing-influenced common understanding).

My DirecTV box’s “CC” menu offers me a choice of “closed captions” or “directv subtitles”. Except for being rendered slightly differently, my random comparisons have never found a difference in the actual content. Years ago, I was a an ordinary consumer participant in betas of the software updates for an earlier DirecTV box. When that pair of options first showed up, I asked what the difference was, but I never got an answer. (Well, I did get an answer, but it was useless. It was to the effect of “one shows closed captions and the other shows directv subtitles”. Jeez, thanks.)

My best guess is that the actual rendering may be the difference, and having both might be some paranoid legal stuff. If you wanted CC that followed the letter of the law, choose that. If you wanted the somehow-enhanced but not letter-of-the-law DirecTV stuff, choose that.

Years ago, I made the gentle suggestion to Amazon Prime video that it sure would be nice to have closed captions available. I expected the sort of non-committal response one usually gets to product suggestions. Instead, I got an email form-letter response from someone in Amazon’s corporate legal department telling me, among other things, where I could file a “complaint” about closed captioning with the FCC. I was not expecting that.

Thanks for posting your article! I was doing research on the history of captioning & found this article. I appreciated the technical details and the info on European captioning. Let me clarify for WJCarpenter and others what the difference between “closed captions” and “subtitles” is.

CLOSED CAPTIONS in videos display more information than what is said; they include cues to *everything* that can be heard. This includes environmental noises (“birds chirping,” “loud thunder,” etc.) and other sounds (“ominous music,” “crowd cheering,” etc.). The “environmental” and “background” sound provides *context* for what is being viewed, and, thus, is important for the Deaf or Hard of Hearing viewer to know.

SUBTITLES display only the transcriptions & translations of spoken dialog. They help you know who is saying what in the video.

Sadly, those who compile DVD videos sometimes do not know the difference, and they end up mis-labeling a video as having “closed captions” when it only has “subtitles.”

Question: about when did subtitles begin appearing in “player point-of-view” video games? I reckon it was around 1999 or 2000. Is there any history on that?

What I would really love is a modern device (Blu-ray player, preferably even a 4K Blu-ray player) that’s able to decode the line 21 captions from DVDs.

There were many TV series released on DVD (that are animated shows from the 80s-2000s and therefore not in high definition) that, for some reason, lacked the DVD subtitles but DID have closed captioning. Watching on a CRT, this was fine as you could just enable the captions – and even on a HDTV, if you use a DVD player with composite output into the TV, the TV will decode them. But anything high definition no longer conforms to the antiquated NTSC standard and therefore that information is lost.

I know the PlayStation 3 did have a CC decoder, and to my knowledge it was one of, if not THE only Blu-ray players that could do this – but I’ve moved on and use my Xbox One X to play 4K Blu-rays now, and still miss the captions.

On a different note, I help preserve history and digitize VHS tapes that were recorded from TV, since many of those programs weren’t made available commercially (especially local news broadcasts from years past). The best way is to plug a VCR directly into an analog capture device and save the video uncompressed, before I do some filtering on it (deinterlacing and resizing to 640×480) and encode it with some other codec. But again, that removes all caption data. Does anyone know if there is a way to open a video file in some program and, provided the capture card doesn’t crop the input, it should be able to see line 21?

Danny, just curious if Xbox 360 or Xbox One/X/S has the ability to show CC from older DVDs with no subtitles (eg Tales from the Darkside, King of Queens, and Are You Afraid of the Dark).. I understand that PS3 shows CC on DVDs as well as Blu-rays correct? I recently upgraded to a Samsung smart TV that has no component or composite ports for the RGB cables.. my old Samsung TV manufactured in 2015 has the ability to show the CC. I would love to be able to see the CC when I play DVDs on the new TV as I’m deaf..

Danny, does PS3 play CC on DVDs as well as Blu-rays? I recently upgraded to a Samsung smart TV with only HDMI ports (no component or composite ports).. would like to be able to see CC on my dvd sets of King of Queens, Tales from the Darkside and Are You Afraid of the Dark on my new TV.. any help would be appreciated 👍

Danny, drop me a message over on Hackaday.io and we can discuss this in more detail.

Thank you kindly for all the details and information. I have been noting different movies and shows online that have difficult “Closed Captions” as opposed to “Subtitles” hoping that help and hope could be better afforded those with low vision and/or low hearing or no hearing, for that matter and am encouraged to see in 2021 technology and beyond, the equal protection of the law (U.S.A.) may afford equal opportunities to enjoy, preserve, and protect the liberty interests identified in many of these comments. This basic is helpful, in any regard: [ CLOSED CAPTIONS in videos display more information than what is said; they include cues to *everything* that can be heard. This includes environmental noises (“birds chirping,” “loud thunder,” etc.) and other sounds (“ominous music,” “crowd cheering,” etc.). The “environmental” and “background” sound provides *context* for what is being viewed, and, thus, is important for the Deaf or Hard of Hearing viewer to know.

SUBTITLES display only the transcriptions & translations of spoken dialog. They help you know who is saying what in the video.] *From rrockwell, April 29, 2021. And yes, the original article is older while the videos I found attempting to explain British and American viewpoints on this helpful and interesting article allows for more research that could be very profitable while providing for a more humane, considerate way to help those of us who have low vision & low hearing challenges. Thanks to all those who comment!