As [Joshua Bird] began his foray into the world of film photography, he was taken back by the old technology’s sheer hunger for light. Improvised lighting solutions yielded mixed results, and he soon realized he needed a true camera flash. However, all the options he found online were large and bulky; larger than the camera itself in some cases. To borrow his words, “[he] didn’t exactly want to show up to parties looking like the paparazzi”. So, he set about creating his own compact flash.

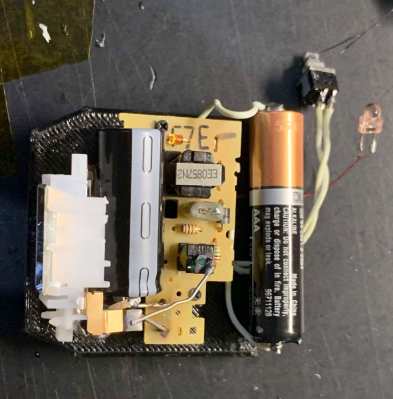

Impressed by the small size and simple operation of disposable camera flashes, [Joshua] lifted a module out of an old Fuji and based his design around it. An existing schematic allowed him to attach the firing circuitry to his Canon’s hot shoe without the risk of putting the capacitor’s 300 volts through the camera. With that done, he just had to model a 3D-printed case for the whole project and assemble it, using a few more parts from the donor disposable.

Of course, as it came from a camera that was supposed to be thrown in the trash, this flash was only designed for a specific shutter speed, aperture, and film. Bulkier off-the-shelf flashes have more settings available and are more capable in a variety of environments. But [Joshua] built exactly what he needed. He now has a sleek, low-profile external flash that works great in intimate settings. We’re excited to see the photographic results.

This is not the first photography hacker we’ve seen breathe new life into disposable flashes. Some people see far more than a piece of camera equipment in old flashes, though, with aesthetically stunning results.

[via reddit]

When I was into film photography back in the ’80’s I found that the greatest improvement to my flash photography was to use a slave flash pointed usually at the ceiling, it gave far more natural illumination.

It’s quite an easy hack to take an existing (bulky) flashgun and add a slave trigger (which I did myself back in the day), then the big flashgun can be left somewhere in the room while you ‘work the room’ with your camera with small flash.

The build is really nice, but you will soon learn all the reasons why proper flashes are large and bulky.

– flash is too close to lens, you will get red eyes effect

– flash is too close to lens, there will be no enough shades and images will look flat

– flash area is small, shade edges will be too sharp

– this flash is too weak for larger distances (but for rooms it might be enough)

However, there is one thing where this flash will be perfect: for triggering slave flash. Now get a proper large flash, and build a slave flash trigger. :-)

O, and when you get a large flash, to get better smoother shades, take a sheet of paper and a peace of duck tape, and make a bouncer for the flash.

agreed, I still have my big flash from decades ago, and still use it. Get it a either a good 30cm away from the camera or indirect bounce light with it… Great for film and digital..

Be careful with old flashes on new cameras. The old film cameras used a switch to trigger the flash. New digital cameras use…digital (or FETs) and some old flashes have trigger voltages that are too high for these. Charge up your flash and put a voltmeter across the trigger connector. If you see more than 5 or 6 volts, don’t try to use it with a digital camera. http://www.botzilla.com/photo/strobeVolts.html

I built a tiny PCB (which fits inside most old flashes) from info I found on the web that will convert a high voltage trigger to a safe voltage. You can buy these as well, but they are cheap to make. Sources for prebuilt safety adapters: https://www.shutterbug.com/content/using-older-electronic-flash-digital-cameras-what-works%E2%80%94what-doesn%E2%80%99t

Details of my PCB here: http://ka1axy.blogspot.com/2013/01/converting-old-photo-strobe-to-low.html

This is why most pro-sumer DSLRs did not have a hotshoe. They might have had a PC socket, but that had lots of warnings attached. I liked that Sony used the Minolta digital era hotshoe, so there was a supply of low volt strobes available, and there were plenty of HV to 3V ISO shoe converters. But it wasn’t the old ISO hotshoe, so even if you were sure your 285HV was “digital safe” you couldn’t drop it on a camera that was only rated as 3.3v and not the 6v that older “safe” strobes used.

I have put a multimeter across the pins of several strobes i have. A cheap yard sale find that runs off 2AA batteries had around 530V; it didn’t fire when measured so I know it took some current. An old set of Braun studio lights showed over 100 V, but fired almost instantly so what the actual charge was I couldn’t measure with a disposable multimeter. And some mixed 285s, some labeled HV and some not, the pins on the shoes does settle down around 5V when charged, but bounces a lot while charging. And I haven’t had much luck measuring across the PC cable; tiny sockets, small pins, cheap meter probes.

As for why Vivitar labeled the newer low trigger voltage strobes (newer, like late 80s) HV, I’ll never know.

Why are some newer cameras only supporting up to 3.3V? Small transistors able to switch up to 40V or so are very common.

Back in the day I used tinfoil glued to cardboard, which was angled in front of built-in flash of my Canon 20D. To angle the tinfoil I cut holders out of empty toilet paper rolls, which stayed decently over the camera body. With this zero-dollar solution the tiny built-in flash bounced up, so I would suggest him to design and 3D print a small door/flap/whatever to his flash so that he can choose between angles, direct flash, diffuser…

It seems to be a trend to use direct flash, though. One veteran photographer said that “it’s the worst favor you could do to a talent”, meaning that he wants people to look their best in his photographs. On the other hand, lomographers might use old (& sometimes bad) gear, expired film, direct flash, leaking light, etc. as part of their creativity, for artistic effects, and so on, because they don’t want clean photos.

Anyway, he said he reached his goal… Let him experiment, maybe one day he has grown out of the small flash and got a bigger gun. :)

Interesting, I generally just turn flash off and up exposure time when using my camera – or add more lighting to scene in the first place… I really hate flashes anyway, so unpleasant to be around, though they do have their uses.

And inbuilt flash is generally not good for the image quality, but that defector idea has merit, and is definitely cheap enough to play with – better if you can point it to the wall or even floor (which for most inbuilt DSLR flash would mean camera on its side so pointing to the ‘wall’ still – though some do have flash offset from the lens as is more common on smaller camera) at will for the best lighting direction. So perhaps that same cardboard and foil idea with a sliding pivot for those split pin type things often used to animate silhouette card puppets for kids – giving adjustablity, and mount it probably on the common inbuilt DSLR flash’s own support arms where it pops out of the body.

With the human eye deceiving you on the REAL light levels, adjusting the exposure time may not do the job.

The original rule was, expose for the highlights, fill the shadows.

Yes, add a fill light, either by a reflector or second source.

I’ve even used a white handkerchief on the flash as an improvised “Soft Box” effect.

Using a Digital means its easy to see if the exposure and lights are wrong after the shot anyway – doesn’t cost anything but a little time to try again (I make no claim to be at all a pro at this – read around it, do some of it, but mostly make it up as I go along, and infrequently enough its back to the camera manual to find out how I change setting x).

I’ve got a few film bodies now I want to have a play with just because, but I never had a real camera with film (a throw away style single use and that one step up reusable, neither of which really count, is all I can remember before digital got good and cheap) in my life to need to actually know the exposure and lighting setup needed before taking the shot, and its not a high priority to me when DSLR, even my old and cheap ones do a job on par with the best you get out of most film I’ve ever played with anyway.

Some people can simply turn the flash around and point it at their tin foil hat to use as an excellent diffuser. They are lucky people. The rest of us have to invent things such as you did.

Nice compact size – and whilst the two comments above are true, it’s remarkable what you *can* achieve with a little diffusion on a small flash. The old reporter’s fag-packet trick and the 35mm film container trick work wonders.

Fag-packet – cut the bottom off a pack of cigarettes and push it over the flash, using the reflective paper inside to bounce the flash to the ceiling. Reporters always smoked, so always had an empty packet to hand.

35mm canister – find a semi-opaque white 35mm film canister, and cut a hole in the side to slip over the end of your flash. The film canister will both diffuse the light and make it more omni-directional, meaning you get a good amount of bounce off walls/ceiling to soften it further.

These tricks also work well with built-in flashes on POS/mirrorless and low-end DSLRs. High-end (D)SLRs never have built-in flash, as it’s never optimal, and a radio flash controller is much more reliable / controllable than a simple slave.

I like the ide to put “flash” and “stealth” in one sentence :D

Undersize single battery (AAA) used for the disposable camera flash which aren’t known to be efficient. The original design was for AA size. Also soldered in battery, so not practical when you need to swap a battery.

ISO400+F/10+3m -> guide number is 7.5 not 50. This can also be seen from the size of the capacitor. Take a look at a flash capacitor that has a guide number of 50. another reason to be bulky. :-)

As I recall, small flash units were available for under $20 at early camera shops.

But wait, there’s more..

I still have one..

Mine was $15 , I still have it, and it might still work. The original CANNON brick one does.

I’ve bought some neat ones for under $5 at estate sales and the like. Have one with a collapsible metal reflector; takes actual bulbs and 2 12v cells. A tiny little East German flash I got from an old lady who sold me her camera; two AA, bright as hell for the size.

Go pester old shutterbugs, you can talk shop and walk away with some knowledge AND a neat trinket.

The best feature of a flash like this vs. a modern one is the fact it flashes only *once*.

A modern flash, especially one built into newer (like post-2000) cameras, flashes a pre-exposure metering flash, JUST long enough ahead of the main flash to cause the blink reflex to kick in, making at least a quarter of the people in a group look a bit dopey.

This a regressive step from the later film-based SLRS, that actually did the flash metering by reflected light off the film itself, during the real exposure, and terminated the flash when enough light had hit the film. It was genius, but came about a decade after this classic A-1 used here.

For people photos now, I usually do a metering exposure first, lock the settings, and do the actual exposure in manual mode. Many dumber point&shoots don’t let you do that though.

Reminds me a little of the tiny SB300 Nikon flash units

With (some) homes boasting smart lighting systems … Shouldn’t it be possible to wire in the existing lamps into a photography setup?

Depends on what you mean

There are lighting setups that use lamps as light sources (otherwise known as continuous lighting). I’ved use them in the past for portrait shooting of say, an office staff so everyone can sit on a stool in front of a background/location and quickly get into position, shoot, and go.

Otherwise if you’re suggesting say, bring lights to full brightness quickly in sync with the shutter, I would assume the systems would not be fast enough to respond to the shutter press input to brighten and darken back down.

Generally speaking, and old film camera only had the shutter fully open when you used a slow shutter speed, like 1/60 or 1/100 if lucky. The camera had a mechanical switch that clicked when the shutter reached full open, that is what closes the circuit for a flash. The capacitors dump the charge through the bulb, and a little bit later (ns measurements) the bulb hits peak brightness and then extinguished before the shutter starts to close.

Higher shutter speeds never had the whole film exposed at the same time, it was a mechanical rolling shutter. So if your light source started too early, it may not hit the target when the target is detected by the film. If the strobe took too long to strike, the shutter could be closing by then.

All of that seems pretty obvious once it’s spelled out. The issue I see with a smart home is latency. What is the fastest speed you can guarantee the camera can talk to the server; that the server can talk to the lights; that the lights can reach peak brightness AND get back to normal? What is the slowest guaranteed speed those can happen? All of that would determine when the camera could signal to tell the house “give me light now”. Might be the communication is slow, so there would be a measurable delay from button press to shutter opening. Might be lots of radio noise so the latency isn’t stable and only some lights trigger.

This is why some people still use light sensitive triggers instead of radios. A tiny $10 box stuck to the bottom of a strobe detectes changes in light. Whether that is a little CdS or half an optocouple, the other flashes will trigger it. The latency of “close circuit -> light emitted” is short enough that you can stack them. A radio based TCP stack, though, could have issues. People do use radio based triggers, but they aren’t running on TCP or even UDP.

I seem to remember Canon making a low-profile flash in the 90s that is barely bigger than this hack. I can’t find it right now but my uncle had a midrange 35 mm SLR that had a unit that was effectively a rectangle with a hot shoe sticking out of the bottom.

(Usual disclaimer of yes I know hacks are valid and this is cool.)

Stealth? I don’t think so! I used to own a Canon A1 and I was fond of it, but the shutter and mirror were loud like you were racking an automatic pistol

Oh yes, and when it gets old, it’s event noisyer, very similar to the AE1’s shutter.

I use Leica M film cameras, they’re quiet, not very convenient, but quiet.

When students asks me how to take away the film of a disposable camera, I allways show them, after taking out the film,

that if the flash circuit is loaded, and if you open the top of the camera with cisors, for instance, you could short circuit those two little bits of metal comming out of that 330 uF component, and ZAP! we get a nice noisy spark, They love it ;o).

Of course the cisors handles must be non conductive ;OD

I’ve recovered a bunch of theese flash circuits because I’d love to put a lot of small flashes units together in an enormous rig :

the biggest the light source is, the softer the lightnig is.

At their peak, film cameras with focal plane shutters could sync flash at 1/125th second. You can get faster sync speeds with a leaf or diaphragm shutter, but they peak at around 1/400th.