Imagine visiting a home that was off the grid, using hydroelectric power to run lights, a dishwasher, a vacuum cleaner, and a washing machine. There’s a system for watering the plants and an intercom between rooms. Not really a big deal, right? This is the twenty first century, after all.

But then imagine you’ve exited your time machine to find this house not in the present day, but in the year 1870. Suddenly things become quite a bit more impressive, and it is all thanks to a British electrical hacker named William Armstrong who built a house known as Cragside. Even if you’ve never been to Northumberland, Cragside might look familiar. It’s appeared in several TV shows, but — perhaps most notably — played the part of Lockwood Manor in the movie Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom.

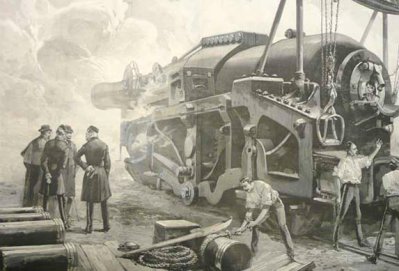

Armstrong was a lawyer by training but dabbled in science including hydraulics and electricity — a hot topic in the early 1800s. He finally abandoned his law practice to form W. G. Armstrong and Company, known for producing Armstrong guns, which were breech-loading artillery pieces ranging from 2.5 inch bores up to 7 inches. By 1859, he was knighted and became the principal supplier of armaments to both the Army and the Navy.

A Vacation Destination

By 1862, Armstrong was sorely in need of a vacation. He had spent time in Northumberland as a child, specifically in the town of Rothbury, so he returned there to relax.

He enjoyed it so much that he decided to buy land and build a modest house in the area. The original house was really just a hunting lodge and didn’t offer much in the way of luxuries, but Armstrong equipped it with furnishings suitable for a much finer house. Becoming even more enamored with the area over time, Armstrong decided to expand the house in 1869. An architect named Shaw quickly drew up the plans, but the execution would take over 20 years to complete.

Apparently, Armstrong was a difficult client for an architect. He was prone to changing plans on the fly and, because of this, the end result is a house that could perhaps best be described as disjointed.

Powering Up

Armstrong had a laboratory built where he would experiment with electric current. The room is now a billiard room and has been since 1895. Prior to that, though, the lab must have been a busy place, indeed. Armstrong built dams to create five separate lakes on the property. In 1868, a water mill provided mechanical power and by 1870, a Siemens generator turned the site into what is thought to be the world’s first hydroelectric power station.

Armstrong was an avid art collector, so in 1878 he lit up his collection using arc lamps. Arc lamps were not optimal for nearly anything, however, much less viewing works of art. Arc lamps generally produced a harsh light and tended to flicker and hiss. While the lamps were not too bad for street lighting, they certainly weren’t ideal for general use. But at the time, Edison’s incandescent bulb was a year away from being invented and even further away from being both practical and available.

Let There Be Light

While Edison gets all the glory for inventing the incandescent bulb, lots of people were working on parallel research, and at least one of them independently struck on a workable design. While Edison found carbonized cotton and bamboo as a suitable filament around 1880, inventor Joseph Swan was working with carbonized paper as early as 1850 and had a working but impractical model in 1860. The problems included the lack of a reliable source of electricity and the difficulties in drawing a good vacuum. Swan invented a mercury pump to solve the latter problem, an approach also used by Hermann Sprengel.

It looks like Swan found cotton as a suitable filament about the same time as Edison. His own home was the first to be lit with bulbs from the Swan Electric Light Company, of course. He also provided 1,200 bulbs for the Savoy theater in Westminster which until that point had been lit by gas. While the theater was having its lights installed, the home of Swan’s friend William Armstrong became the second dwelling to be lit by Swan’s bulbs. After all, in December 1880 the house already had electricity. Although the lights were far from perfect, they fit with the modern conveniences that Armstrong was fond of.

The bulbs had low resistance and required thick copper wires. They also burned out very quickly. But it did give Cragside the distinction of being one of the first homes in the world with electric lighting and doubtlessly the first to be lit by hydroelectric power.

Ahead of the Curve

Armstrong might not be a household name, but he did quite a few things of note. He built the mechanism that operates London’s Tower Bridge. He also developed a method to store hydraulic energy called the hydraulic accumulator. He was a correspondent with Michael Faraday, who we do often remember. He also used hydraulics and friction to generate static electricity in an apparatus similar to a Van de Graf machine that was seen in a show at the London Polytechnic. No wonder he has been called “the magician of the north.”

It seems Armstrong was ahead of his time in many ways. In addition to the modern appliances in his home, he was a strong proponent of renewable energy. He recognized the power of water, obviously, but also of the sun. He also thought coal was wasteful and predicted that Britain would cease coal production within 200 years.

The house still gets some of its power from a rebuilt hydroelectric plant on the site. There’s a video you can watch about the project and see a glimpse of Armstrong’s remarkable “hunting lodge” below.

“He also thought coal was wasteful and predicted that Britain would cease coal production within 200 years.”

Not quite, but working on it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coal_mining_in_the_United_Kingdom#Decline_in_volume

The prediction is good until 2063, so it might work out even if they push the new one through.

Britain will probably have to massively ramp up coal mining so all the new electric cars can be charged without causing daily outages.

EV owners rarely charge their cars during the day. They plug them in and have them charge overnight when there’s a significant surplus of electricity available. Plus wind farms tend to generate more electricity overnight so if there were somehow not enough surplus at night, just add more wind power. Coal power is much more expensive than wind power in any case.

Wind farms apparently do not generate more electricuty at night

https://carboncounter.wordpress.com/2015/07/10/are-wind-farms-more-productive-at-night/

The amount of electricity supplied by renewables is currently nowhere near enough to charge electric cars in the event that internal combustion engines are phased out completely (due to happen in the next decade/s). I doubt that capacity will grow sufficiently in time (not just the actual capacity but also the grid-level storage infrastructure to take away the fluctuation of renewables). The enthusiasm for EV is probably not being matched by infrastructure development. Yes, car batteries can act as a kind of storage infrastructure but I doubt that they will have infinite charge/discharge cycles (people will unpleasantly surprised when the battery lifetime is far shorter than the lifetime of the rest of the car). We will then either have to have coal (available underground right now in the UK) or will have to keep importing petroleum products to fire power stations to generate the electricity. Nuclear is another option but it has obvious issues (and I don’t think the UK has massive uranium deposits).

Wind for night, solar for day – already cost-competitive vs coal and set to widen the gap. Proper energy management systems and demand response to make sure the charging happens while the grid is oversupplied – lots of capacity goes unused at the slow times.

Wind for when it’s windy, in the UK that can happen during the day too!

The UK grid is already down to its last 3 coal-fired power stations, and they’re due to close by October 1st 2024.

UK had to fire one up again the other day:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-58469238

Not very windy and gas prices are going up apparently.

Good storage infrastructure will be required to avoid this in future.

I would disagree about Armstrong not being a household name. But it might rather depend on the household.

I think of floor tile.

B^)

or the method of steering my car.

Isn’t that Ackermann?

I think of Edwin Armstrong, an early radio inventor. Quite an impressive resume.

>I would disagree about Armstrong not being a household name

Yes, but that would be Neil.

Also dependent on the family: one’s idea of what one might call a “simple hunting lodge”

To an amateur radio operator, “Armstrong” is the old-style antenna rotator.

I was my dad’s Armstrong TV rotator circa 1950

If you go back early enough in any field, there was a lot of opportunity for “amateurs”. Indeed, early enough and you can’t be trained in the field, no specific course.

Such as making your own X-Ray machine!

Van de Graaff generator (double a, double f) is the correct spelling.

Thaanks ffor infforming us aabout thaat!

B^)

I learned my spelling of VDGG (double a, single f) from Peter Hammill (double m, double l)

This was covered some time ago by The Register as part of the Geek’s Guide to Britain series. Well worth a read.

https://www.theregister.com/2019/03/18/geeks_guide_to_britain_cragside/

Back in the early 1990s it was the subject of a TV programme in Britain’s Open University Arts Foundation Course. One thing I remember, which is not mentioned in the article, is that the electricity was carried not by familiar wires, but by thick copper bars laid under the floorboards. Sadly the programme is not available for viewing:

https://www.open.ac.uk/library/digital-archive/program/video:FOUA239F

The method of house construction has a similarity to Widow Winchester’s mansion.

This mansion, did not have electricity, but indoor plumbing and heating would be a big deal for a wealthy man in this South Texas area of the US in the 1880’s.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulton_Mansion_Historical_Site