A long time ago, there were these vinyl recording booths. You could go in there and cut a 45PM record as easily as getting a strip of four pictures of yourself in the next booth along the boardwalk. With their 2021 Hackaday Prize entry called VinyGo, [mras2an] seeks to reinvigorate this concept for private use by musicians, artists, or anyone else who has always wanted to cut their own vinyl.

VinyGo is for people looking to make a few dozen copies or fewer. Apparently there’s a polymer shortage right now on top of everything else, and smaller clients are getting the shaft from record-pressing companies. This way, people can cut their own records for about $4 a unit on top of the cost of building VinyGo, which is meant to be both affordable and accessible.

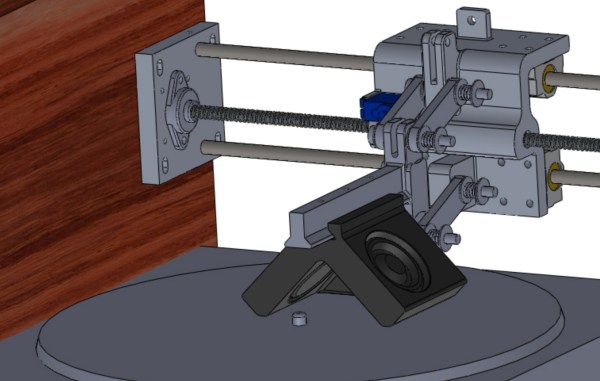

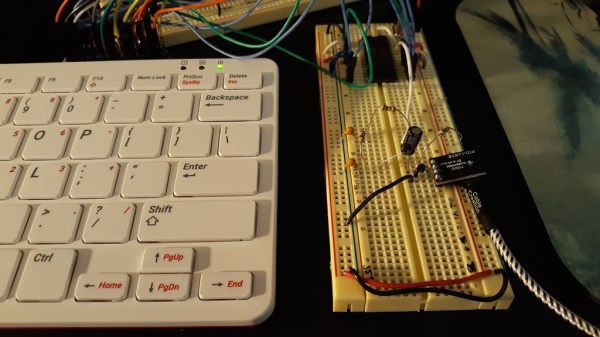

You probably know how a record player works, but how about a record cutter? As [mras2an] explains over on IO, music coming through a pair of speakers vibrates a diamond cutting head, which cuts a groove in the vinyl that’s an exact representation of the music. Once it’s been cut, a regular stylus picks up the groove and plays back the vibrations. Check it out after the break.

[mras2an] plans to enter VinyGo into the Hackaday Prize during the Wildcard round, where anything goes. Does your project defy categorization? Or are you just running a little behind? The Wildcard round runs from Monday, September 27th to Wednesday, October 27th and is your last chance to enter this year’s Prize.

Not your kind of vinyl cutter? We’ve got those, too.

Continue reading “VinyGo Stereo Vinyl Recorder Will Put You In The Groove”