Even if you aren’t a giant history buff, you probably know that the French royal family had some difficulties in the late 1700s. The end of the story saw the King beheaded and, a bit later, his wife the famous Marie Antoinette suffered the same fate. Marie wrote many letters to her confidant, and probable lover, Swedish count Axel von Fersen. Some of those letters have survived to the present day — sort of. An unknown person saw fit to blot out parts of the surviving letters with ink, rendering them illegible. Well, that is, until now thanks to modern x-ray technology.

Anne Michelin from the French National Museum of Natural History and her colleagues were able to foil the censor and they even have a theory as to the ink blot’s origin: von Fersen, himself! The technique used may enable the recovery of other lost portions of historical documents and was published in the journal Science Advances.

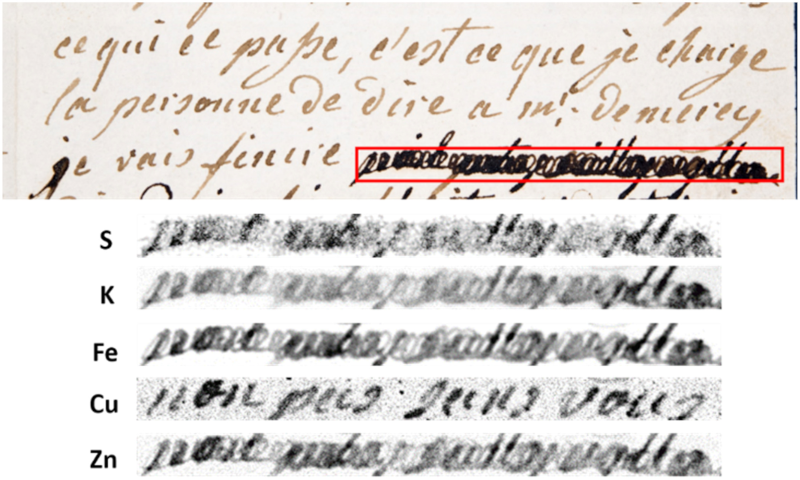

Michelin’s team used X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy and found that the author of the letter used ink of one composition, and the censor used another that was quite different. The different fluorescence under X-ray allowed recovery of some of the hidden letters. Further data analysis allowed the interpretation of much of the text.

One interesting result: the ink in the blots matched closely with von Fersen’s ink, so the researchers think he blotted out the passages himself. Small wonder since they included lines from the Queen like:

“I will finish not without telling you my dear and loving friend that I love you madly and that I can never be a moment without adoring you.”

Probably not something you’d want the King to read later.

Granted, most of us don’t have X-ray spectrometers laying around. But this is an interesting technology detective story and who knows? Maybe it will inspire a hacker-developed spectrometer build. After all, you can build an X-ray machine. You can even make your own tube if you want to go that far.

True then, as it is today, nothing is ever truly deleted. The moral of the story being if you don’t want something discovered, never commit it to physical media such as paper or hard drive.

The one who never made mistakes never accomplished anything. I’ve seen many declassified papers online that have been blacked out and photocopied to avoid this type of attack. I had never read before how it was done so today i learned.

The X-ray tube is easy… it’s the silicon drift detector and electronics that are hard.

No guys… varying the excitation energy is NOT what XRF is about. It’s about detecting the different x-ray energies EMITTED (fluorescence) which are characteristic of the element being excited.

> most of us don’t have X-ray spectrometers laying around

You could take multiple X-ray with different thickness of metal between the tube and the detector. It would not be the same you would be in effect adding a high pass filter where you are manually increasing the cut-off frequency. But with a large enough number X-rays at in effect different cut-off frequencies similar end results should at least be possible, but it would be much much slower.

You can make much more effective filters not with different thicknesses, but with different *elements*: These exploit the different K edges of the elements, and a series of close element pairs (e.g. tin, antimony) can yield quite fine spectral resolution — certainly adequate for element identification. The so-called “balanced K edge filter” or “Ross filter” can be used with simple non-energy-selective detectors, even with film, like when it was invented in 1926.

There is nothing special about this.

In forensics there are lots of tricks in use to separate different ink types from each other.

From UV lighting, polarized light, and probably also chemicals that dissolve or discolor the inks in different ways, and there probably are long lists of other techniques that I do not know about.