While Star Trek’s transporter is hard to imagine — perfect matter movement across vast distances with no equipment on one end — it may not be the most far-fetched piece of tech on the Enterprise. While there are several contenders, I strongly suspect the universal translator is the most unlikely MacGuffin. After all, how would you decipher a totally unknown language in real-time? Of course, no one wants to watch 30 episodes of TV about how we finally figured out what Klingons call clouds, so pretty much every science fiction movie has some hand-waving explanation for speaking the viewer’s language. Farscape had microbes, some aliens have telepathy that works with alien brains of any kind, and still others study English from afar for decades off camera. Babelfish anyone?

I was thinking about this because of an article I read by [Alizeh Kohari] about [Jiaming Luo’s] work using AI to decode dead languages. While this might seem to be similar to Spock’s translator, it really isn’t. Human languages change over time and distance. You only have to watch the BBC or read something written by Thomas Jefferson to see that. But there is still a lot in common, at least within certain domains.

You’re Only Human

If you are a native English speaker, you can probably puzzle out a lot of words given a text in, say, Spanish or French. Most of these languages either started with or borrowed from Latin and share roots with languages like Greek, so you can often puzzle out a sign with a little context. Now try that with Arabic or Mandarin. Most of us don’t have a clue. Do you read right to left? What are the characters? There’s nothing to grab onto unless you know the language or one that is similar. For example: “每天閱讀 Hackaday” probably doesn’t give you any clues other than it is about Hackaday.

The AI isn’t much different. The software learned how languages change as they evolve by studying patterns between related languages like Ugaritic and Hebrew. You might think languages develop ad hoc, but there are definite patterns — at least, among human languages.

For example, although not all languages have the same words for colors, it has been known since around 1969 that humans tend to develop words for colors in the same order. That is black and white get names along with red. Then, later, names for other colors appear. You can watch an interesting video about this effect below.

Close Relations

Assuming that the AI could translate one related language into another, what happens if you feed it languages that are related, but we no longer know how to read?

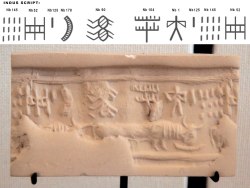

The problem for the AI is that no one knows what languages might be related to the Indus script. [Luo] and his team have done work to devise an algorithm that can tell how close two scripts are even if it can’t understand them. This could help. We’ll see if his computer can eventually read the dead Indus language.

If this works, it could open up a lot of archeology. There are many languages that have been forgotten like Etruscan and Rongorongo. If you knew they had morphed into other languages we do know, this could help unlock them. Even languages we do understand fairly well today were not always known in modern times. Egyptian hieroglyphics, for example, were a mystery until the discovery of the Rosetta stone which had the same message in the hieroglyphs, Egyptian demotic script, and Greek. At least we knew how to read Greek.

AI Hype

If we had the true universal translator, it would be fun to see what the dolphins and the bees are saying to each other. It seems like if we could do that, reading Indus would be easy. The truth is, though, AI is a long way from being able to totally replace humans and human insight into creative problem solving and that’s important to remember as people look to us as people who understand technology to help them make decisions about AI.

For example, researchers think the people who wrote the Indus script seals wrote right to left because sometimes the left characters are scrunched up as sometimes happens when you get close to the edge of your paper. However, since the seals were probably meant to be used as stamps, that doesn’t necessarily imply the language itself is right to left. For instance, Chinese used to be written top to bottom and right to left, but in modern formats is written row-wise left to right. Both styles persist, but you know which way to read from context. Insights like that are still the purview of humans, at least for now.

I have read recently that AI may already be conscious. If you know much about how the brain works and how modern AI works, you’ll probably find that statement to be as unlikely as I do. We may one day replicate an electronic brain that embodies that thing that makes us “human” or even just conscious. But that day seems far away, indeed. Besides, if we do, who is to say we won’t have as much trouble speaking with them as we do with dolphins?

There are also hundreds of knotted-cord quipu that have been digitized. Similarly, analysis seems to show statistical patterns more akin to language than accounting (zipf’s law vs benford’s law), but only “about one” of them have been translated. The language encoded ought to be closely related to Quechua, though.

Really? I thought quipu were more like memory aid than actually writing. Do you have a link to an article?

This is a good overview:

https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-inka-empire-recorded-their-world-in-knotted-cords-called-khipu

My part was https://projects.csail.mit.edu/khipu/

Thanks for the links and I wish you well on your project, can’t wait to read what the Inka Empire had to say.

Universal translators, babelfish? Don’t be silly, everybody knows all aliens are actually speaking Rigelian!

+500 Quatloo…

It’s way more important keeping languages alive than resurrecting dead languages. Some languages have very few fluent speakers mostly older, so a lot of effort put into keeping the language going. So drop words into an article or speech otherwise in another language. Immersion classes for kids. Even immersion for adults. Add words to keep the language relevant. Keep the elders alive so they can talk to the kids. They should be paid for their time, learners paid for their time learning. I just saw a story about a wordle variation for a Native language. Write books in the language. Have hockey commentary in a different language. Dub Star Wars in Navaho, though that’s a bad example since they are better off. Twitter feeds that introduce a word a day. Put organizations in your will to perpetuate the language.

The fight to keep a language alive is hard, but the fight is strong.

Were people NOT trying to keep elders alive before your comment told them to?

There are always things going on in the world that are awful, but that doesn’t mean we have to stop every other human endeavor — including ones like this, that attempt to understand our past — just because there’s one aspect of humanity that is on the verge of being lost.

Yes, we should do everything we can to preserve older languages. As someone who grew up speaking English, however, and whose genealogical heritage includes Dutch, French, German, and Swiss, among other things — all languages that aren’t in danger — and who would like to try to improve his college French, or perhaps learn a bit of Navajo, or Russian, or Japanese, but doesn’t have the time or energy to do even that — saving languages in danger of extinction is not something I’m in a position to do right now.

Having said that, if I were to find myself in a position to help with this endeavor, I would almost certainly jump on board. If I found myself in a position to help preserve a dying language, I’d jump on board that effort to.

Now, having said that, however, as much as it pains me to say this, but perhaps the dying of languages isn’t the end of the world. We have evidence (based on the stories of the “Seven Sisters” in astronomy) that story-telling is at least 100,000 years old — yet written language of any form is only about 6,000 to 10,000 years old. How many languages came and went in that 100,000 year period? We need to remember that the most important thing about language is communication, and even when languages die off, so long as we have a good standard of communication (at current count, we have about 2,500, if I recall correctly), then that is ultimately all that matters — and we should also remember that, as sad as it may be that a language dies off, it dies off because it’s no longer an effective method of communication (albeit, it’s no longer one because not enough people can communicate with it, and not enough people consider it worth the effort to try to do so).

(I really hate to say that last bit, however, because it nonetheless pains me when any bit of culture is lost, even if it makes sense that it’s inevitable.)

Why? I can invent a thousand languages, why is one more valuable except as a record of history. Why do other people NEED to speak them for you?

Just wanted to point out that Star Wars already has a Navavo dub.

Revive dead languages?

How about first teaching people in English-speaking countries to stop mispronouncing Latin and every foreign word that has I or E in it.

During the time Latin was spoken, sadly, no recording devices existed. We can only guess how it was spoken in conversation.

As such your argument is null.

Well unless you have a time machine. You should post it to hackaday.io so we can all share.

All languages derived from Latin pronounce those letters in the similar way. As such your argument is …

Besides, Latin had continuum of speakers after Roman empire collapsed. Catholic church, for example.

Aye, there’s the rub, though: English isn’t a Latin language. It’s Germanic one, with a heavily simplified grammar at that. (Don’t get me wrong, though: English is complicated in many other ways, to be sure. Grammar just isn’t one of them!)

To the extent it even has Latin, it was because the Normans imposed a bunch of French vocabulary on the language (which was already a mangled form of Latin), and then Saxon natives further mangled that in their own Saxony way.

And remember the “French” the Normans imposed on English was Norman French, which was pretty divergent from Parisian French itself.

Actually, there are ways to reconstruct how a written language was spoken – look for example at the “reconstructed pronunciation” of Koine Greek (the common Greek which the New Testament was written in – it’s later and simpler than Classical Greek). Based on things like poetry and scribal errors (where a bunch of scribes are copying the same text which one person reads out to them, and one of them misheard a word) they’ve been able to reconstruct how Koine was pronounced. though I’d guess that’s only possible where you’ve got a massive volume of early copies of a document, such as the New Testament.

Actually, we have a pretty good idea what Latin sounded like. There’s even a lengthy Wikipedia article about it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_phonology_and_orthography

+1

As an European/German, it always hurts to see/hear English TV documentaries from overseas mispronouncing words from Latin, Italian, Greek etc. Even when dubbed, you can still hear the original audio in the background. If, say, DaVinci become Dah-whine-shee, you really want to bang your head against the wall.

Makes me really wish they would re-introduce Latin classes over there. I mean, even people from Spain or France are able to pronounce things right most of the time. Why can’t people from, say, the US get the E / I thing right? It really is annoying. 😔

I really don’t understand this. When I took Spanish in Junior High, I was expected to choose a Spanish name for myself (I chose “Alfonso”). When I took French in college, my professor deemed my name to be “sufficiently French”. Heck, just recently I learned that “Zoe” is a forbidden name in Iceland, and it’s forbidden precisely because it doesn’t play nice with Icelandic grammar.

Yet when it comes to English, it’s only right if it’s pure and unchanged from other languages?

Case in point: Christopher Columbus is the Anglicization of his name; to the best of my knowledge, he was never called this in his lifetime.

As for the E / I thing, which words are you talking about? The Greek ones? The Latin ones? The Germanic ones? We have a big, long rule that starts with “I before E, Except after C”, and then has a big long list of exceptions. Every line of that rule is wrong. About the only good rule of thumb is to figure out what language the word came from, and use that language’s spelling conventions. Even then, though, that rule isn’t perfect.

In any case, the only metric for whether something is pronounced correctly in English is to ask “How do other native English speakers say this?”, not “How do they say this in France or Spain?” This is particularly illustrated when one considers that French and Spanish people get Latin wrong — both languages are merely Latin, mangled over the centuries — but that would only make sense if you think they are trying to speak Latin — but if they did that, then neither French nor Spanish would exist as independent languages!

If you’re talking about an English speaker trying to speak Latin, you have a point. If you’re talking about English speakers saying English words that were originally Latin, then, no, we’re not changing our pronunciation.

If we’re lucky, we might decide to change the spelling after we adapt the word for our use. More often than not, though, we’re not lucky.

Besides, some of those words you think came from Latin, may have actually been obtained when English mugged a Germanic language, and some of our “Latin” words were first mangled by French before English chewed on them.

Also: English has a long history of people, some of them even native English speakers, trying to force Latin grammar and pronunciation rules into the language where they don’t belong. Most of these attempts fail, mostly because even these “Grammar Nazis” can’t reliably stick to their own rules. Case in point, sometimes a verb sounds very wrong when you don’t split the infinitive.

And I, for one, am sick and tired of people telling me how to speak “proper English” who merely look at other languages with envy, without fully appreciating how weird and wonderful and yes, sometimes even downright awful, English really is.

Look up something called “The Great Vowel Shift”, where the English language, for reasons nobody knows, changed the way it pronounced all it’s vowels. Personally I think “The Great Vowel Movement” would have been a funnier name but nobody listens to me.

+500 Quatloo

I have to go clean coffee from my keyboard now…

We are probably 20+ years away from anything that I would call Intelligent that is Artificial in nature. The real problem is that there are 86 billion neurons in human brains, connected together with 100 trillion connections. There is nothing artificial that can simulate that (yet). And the first one will most definitely not using a measly 12 watts on power like a human.

(ref: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_animals_by_number_of_neurons )

Sorry “Computation in the human cerebral cortex uses less than 0.2 watts” – https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.23.057927v1.full.pdf

Well, we may be hallucinating math.

https://thenextweb.com/news/your-brain-might-be-quantum-computer-hallucinates-math

Philosophy never runs out of completely meaningless things to say. It’s refreshing kinda

I really don’t think anything AI generated in this context could be trusted at all, no matter how confident the AI states it is – the premise is clearly sound as languages do evolve and borrow from each other, so the mathematical fingerprints could well end up being comparable. But without some historical context you could easily enough fall into assuming x and y are related closely as they come from the same era and location, and then fit a solution that seems to be consistent, yet for purely human reasons can’t be as there is deliberately very little cross over – you might share geography and have a language you can talk to your neighbors in, doesn’t mean you don’t keep your own language as distinct from theirs as possible.

In many ways the vast array of very distinct dialects of English (some with centers almost as close as a stones throw from each other) around the UK are a case in point of locals being deliberately rather clannish, and for the most part for a very very long time now there hasn’t been isolation, hate, or great cultural differences to hold on to and reinforce that difference…

(its not like you have the entire works of some prolific writer in most of these languages, just tiny fragments that might all be surviving for the same reasons – too much missing data that when you are looking to make something fit you probably can, even if its very wrong).

You wouldn’t just trust what the AI outputs.

But if the AI has shown it can correctly analyze controlled samples then researchers would be able to use the AI outputs as a starting point to begin to piece together the puzzle of an unknown language.

So it wouldn’t necessary be a translator at first, but a research tool.

Yeah, even a crib generator would be super useful, as would additional data points to support/refute hypotheses about which language a given orthography is encoding and/or which might be foreign words or place names (additional possible cribs)

Not saying it can’t be useful, analysis tools are always useful.

But a crib generator that is outright wrong but in ways few people could realize isn’t helpful – and humans have a tenancy to trust blindly the expertise of machines or their ‘expert’ creators – if they didn’t GPS wouldn’t be full of so many hilarious stories of folks following it when its clearly wrong, nor would there be so many folks believing all the various nutty theories in place of the clearly proven hard science and backing it up with the pseudo facts of very twisted statistics, often used vastly out of context too…

Get two teams to generate two radically different mathematical systems then watch the AI still struggle to link both to human mathematics. If you want an example of how dumb AI really is just get two vowels wrong at the same time and watch google’s spell checking code, even the advanced one, get confused. Most of the AI field today is fraud, exaggeration, or cherry picked examples that cannot be integrated into a holistic system required for general purpose cognition.

at the Alexander Graham Bell museum in Cape Breton,amongst

many things is a display that mentions that Alexander’s father,who invented a system to learn any language,apparently worked,though difficult to master.

then there is the joke about european’s who can speak nine languages,none of them fluently.

As for Sci-Fi translations… I notice in the original Stargate movie, Daniel had to spend a lot of time to understand the people on Abydos. But when the series came along, it seems all the people they met, whether advanced or primitive, could speak English. (Except the Unas, it seems). I guess I should be glad as it did help move the plots along quite a bit…

Yeah only so much ‘hold on let me spend hours learning and then translating a language nobodies ever heard before’ can be fitted in the plot lines…

Of course as its established the snake heads (at least Sokar) had a presence in medieval(ish) England (which seems a little lore breaking with when the gate was supposed to be buried, but sshhh), so no doubt all the snakes could speak old English, and obviously they then made nearly all their planets convert to using this far superior (pfft) language, and magically evolved it in the exact same way as the Americans…

I did like that they did at least keep a fair bit of it in, ancient language, Unas, the long dead race with the minefield etc whenever it doesn’t just kill all the episode pacing, maybe even as a tool to ratchet up the suspense – in many ways helps make the series feel more real than many other Sci-Fi series, just that it is there at all. Even Babylon 5 perhaps the most believable realistic modeling of the vast alien universe, with consistent science, interspecies politics harder type Sci-fi had everyone speaking English nearly all the time with no explanation as to why…

I think the issue is that having every species speak their own language — and not just one language, but hundreds! — would be such a hinderance to the plot, that having everyone just speak English except for the rare times where it is necessary to the plot to have language differences, people just shrug and say “yeah, just let me believe everyon speaks English (or Japanese, or whatever language the work is made or dubbed in) and get on with the story!”

Stargate the movie works because figuring out the language is an important part of the plot, and it makes sense given the context. Stargate the series, Start Trek, Star Wars, the Lord of the Rings, and so many other stories work because, despite the nonsensical nature of “everyone speaks the same except when they don’t”, we get the stories, without the encumbrance of dealing with translators, subtitles, and other complications of dealing with multiple languages, but have nothing whatsoever to do with the story being told.

Come to think of it, I have seen entire stories, series, and movies, where not one thought was given to the question of “what does the character do when they have a full bladder?” Come to think of it, how many hours did Han Solo, Luke Skywalker, and Leia Organa run around the Death Star? How many potty breaks would they have realistically needed during that time? In general, we’d rather not know ….

Very true, there is only so much attention to trivial details of living in a real world required, though I suspect when you fall into a trash compactor you can sort your toilet breaks out just fine, you already are a sticky stinky mess…

But I liked in the Stargate Series, and LoTR for that matter that there are times when two characters are talking in another language (when they really have a reason to do so), it just makes it feel real and can be used to really inform the characters and their relationships.

Daniel being sarcastic in fluent Russian with something like ‘I’m conversational, I suppose I’ll get by’ – its fun, and really fits the moment and character (though I’m damn glad they didn’t then stick with Russian, as I can just about struggle to read bits of it here and there, but talk it not a chance, and subtitles when they are a bore when you don’t need them)

Aragorn telling Legolass to shut it at the initial council meeting for instance – immediately without knowing anything of the lore/plot you know those two have some history, and it further reinforces the widely traveled and long lived Duendain rangers skills and knowledge. He could have spoken in English, but why should he there? (Also like many of these moments one where you don’t actually need to have any idea what is said if the actor is halfway competent as the body language does the talking just fine)

Same thing some folks were going on about here with some Workshop in a Marvel? related TV show recently – to anybody who knows anything at all about making having such a real workshop informs you so much on the people involved, and makes the crafting of whatever now an understood and accepted part of the story, hyper accelerated as it no doubt is anything newly made turning up now makes sense (and that is almost everyone – as almost everyone will at least know somebody that does something maker like and probably did a little of it through school, so have seen something resembling a workshop (though these days probably very nanny state, take away all the really fun stuff)).

“Yeah only so much ‘hold on let me spend hours learning and then translating a language nobodies ever heard before’ can be fitted in the plot lines”

When I read the phrase “revive dead languages” in a comment above, I thought, “that would be the worst Jurassic Park plot yet”.

I don’t believe there is any real AI, yet. Now, there’s talk of different kinds of intelligence, apparently like when people point to a computer program and call it AI. Good luck with that.

Emotional intelligence.

That’s a very specific measurement for mental math computations. The generally accepted figure is that the brain uses 20 watts on average.

Unless I missed it, understanding languages in Star Wars is never really explained.

But someone people understand some languages and others dont, including droids not understanding all of them.

And it’s even in the movies where people ask others what someone said as they dont understand.

I guess it’s just assumed that people took the time to learn them.

Which makes the average person in the Star Wars universe a pretty good linguist!

Having a cohesive empire would be hard without it.

I would of thought the most obvious test would be Linear A, the creten Minonan script. It is know there is a relationship with linear B, which has been deciphered, but no linear A tablet has yet been deciphered

Would’ve is an abridgement of “would have” – there is no such syntax as “would of” in the context in which you use it.