For as long as I’ve been driving, I’ve been changing oil. Longer than that, actually — before I even got my license, I did a lot of the maintenance and repair work on the family car. It seemed natural to do it back then, and it continues today, despite the fact that it would probably be cheaper overall to farm the job out. I keep doing it mainly because I like keeping in touch with what’s going on with my cars.

Oil changes require supplies, but the last few times I made the trip to BigBoxMart I came back empty-handed. I don’t know whether it’s one of the seemingly endless supply chain problems or something else, but the aisle that usually has an abundance of oil was severely understocked. And what was there was mostly synthetic oil, which I’ve never tried before.

I’ve resisted the move to synthetic motor oil because it just seemed like a gimmick to relieve me of more of my hard-earned money than necessary. But now that it seems like I might have little choice but to use synthetic oil, I thought I’d do what normally do: look into the details of synthetic oils, and share what I’ve found with all of you.

Old Mechanic’s Tales

Right up front, I’ll say that there appears to be a lot of “folklore” about motor oils in general and synthetics in particular, and a lot of strong feelings among people for whom cars are more than mere transportation. So it’s easy to find videos and blog posts that insist that synthetics are a gift from the lubrication gods, and ones that declaim against synthetics in the strongest possible terms. And of course, each camp looks at the other as heretics, whose lubrication predilections are sure to lead them into a pit of automotive despair and suffering. Such is our polarized world, I suppose.

While I don’t really want to choose sides in the motor oil wars, I definitely do not want to do anything that could potentially damage the carefully tended engines of my cars. Having never run synthetics, I did feel a little due diligence was in order: is it possible for synthetics to cause damage to older engines that have only run traditional oils?

The short answer is: probably not. When synthetic oils first came out, their chemistry was not entirely compatible with current engine technology. Specifically, the early ester-based synthetics caused problems with engine seals containing polyester resins. Those days are long gone, as both engine seal technology and synthetic oil formulations have improved. Modern synthetics have been tested to be compatible with all sorts of materials commonly used in engine seals, like nitrile, silicone, polyacrylates, and fluoroelastomers like Viton. Oils that bear the proper testing certifications have been shown not to cause excessive swelling or shrinking, hardening, or reduction in strength in seal material when exposed to synthetic oil.

So basically, if you’ve got an engine made any time in the last 30 years or so, and you use a synthetic oil that matches the manufacturer’s recommendations, you should be fine.

All About the Base

But what exactly is it about synthetic motor oil that makes it synthetic? And how does it differ from traditional motor oil? As it turns out, there’s less difference than you’d think between the two oils, but the way that they differ is pretty interesting, and the differences revealed the world of lubrication engineering in a way that I never really appreciated before.

All motor oils, traditional or synthetic, are highly engineered products that contain a bewildering array of additives, each with a specific job. However, motor oils all start with a base oil, which falls into one of five broad groups, based on properties such as sulfur content, viscosity, and the amount of saturated hydrocarbons it contains — more on that later:

| API BASE OIL CATEGORIES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base Oil Category | Sulfur (%) | Saturates (%) | Viscosity Index | ||

| Mineral | Group I (solvent refined) | > 0.03 | and/or | < 90 | 80 to 120 |

| Group II (hydrotreated) | < 0.03 | and | > 90 | 80 to 120 | |

| Group III (hydrocracked) | < 0.03 | and | > 90 | > 120 | |

| Synthetic | Group IV | Poly-α-olefin (PAO) lubricants | |||

| Group V | All other base oils | ||||

Group I, II, and III base oils are all derived from crude oil, and the methods used to refine the crude feedstock into lighter fractions suitable for engine oil largely determine the amount of sulfur in the base oil, as well as the concentration of unsaturated hydrocarbon compounds in it. Saturated hydrocarbons are ones where each carbon in the backbone of the polymer is fully populated with hydrogens; in other words, saturated compounds have no carbon-carbon double bonds. This is important because unsaturated bonds are potential sites for oxidation, which can damage the properties of the base oil.

Synthetic, Yes, But…

So since the base oils for traditional mineral oils come straight from the ground in the form of crude oil, surely that must mean that synthetic oil avoids the stain of association with fossil fuels. As it turns out, that’s not the case. If there’s one thing we’ve learned from this “Big Chemistry” series, it’s that almost everything we use in daily life comes, in whole or in part, from petrochemicals. And it’s the same with synthetic oil.

Group IV base oils are almost exclusively poly-α-olefins, or PAOs. Like plastics, PAOs are synthetic polymers, but rather than having massively long and intricately cross-liked sidechains, PAOs are mostly a small number of short sidechains linked together. But, plastics and PAOs have a lot in common, in terms of starting materials and the processes needed to create them.

The starting point for most polymers is natural gas. The primary compound in natural gas is methane (CH4), the simplest hydrocarbon possible and a member of the alkane family, which has a backbone of fully saturated carbons. But most natural gas deposits also have a significant concentration of more complicated alkanes, such as the four-carbon butane, three-carbon propane, and two-carbon ethane. Ethane is the starting point for much polymer chemistry, and can be isolated from raw natural gas by selective condensation.

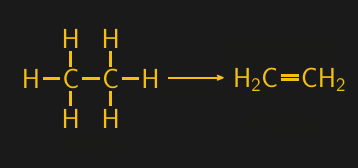

Ethane gas can be converted into ethylene gas by steam cracking, which uses high temperatures and pressures to break down saturated hydrocarbons and introduce carbon-carbon double bonds. Hydrocarbons with at least one double bond are referred to as alkenes, and the alkene version of ethane is called ethylene. And ethylene, with its chemically reactive and centrally located double bond, is an extremely useful building block.

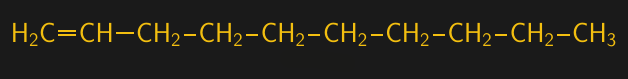

The next step along the way to synthetic oil is making longer chain alkenes from ethylene. The chemical process used for this, the Ziegler process, is complex and beyond the scope of this article – and honestly, beyond my understanding. But suffice it to say that it uses an aluminum-containing organic catalyst to stick multiple ethylene compounds together. The Ziegler process allows fine control over the oligomerization reaction, and can produce alkenes of specific lengths. When the carbon backbone has ten carbons with a single double bond, it’s called 1-decene.

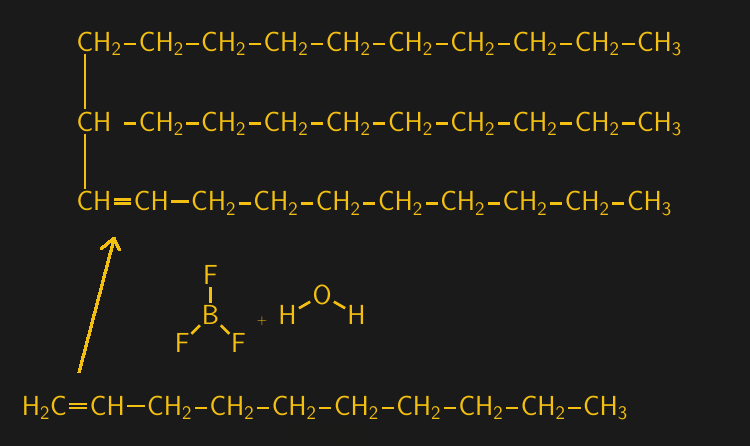

Alkenes, which are also known as olefins, are characterized by where along the carbon backbone their double bond is located. When the double bond is located next to the first, or alpha, carbon, the resulting molecule is called an alpha-olefin, or α-olefin. 1-decene is the most common α-olefin used in the production of poly-α-olefin, which is accomplished by reacting 1-decene with a catalyst of boron trifluoride (BF3) and either water or an alcohol. This reaction targets the vulnerable double bond on the α-carbon of 1-decene, linking it to the α-carbon on another 1-decene molecule.

Unlike in plastics, the polymerization reaction is only allowed to go for a few rounds, yielding small oligomers of 1-decene. Five or six rounds are typical, resulting in a PAO that is completely devoid of sulfur compounds and unsaturated bonds — the remaining double bond from the last reaction is saturated by reacting the PAO with hydrogen gas under pressure. That removes the last possible site for oxidation, making for a stable PAO base oil.

Almost Done

PAOs are manufactured in huge volumes and shipped to blending facilities where the base oils are mixed together to achieve the proper viscosity. Additives such as detergents, dispersants, anti-foaming agents, and anti-wear agents are added to meet the specifications of the final product.

While the name may be misleading, in many cases synthetic motor oils hold the edge over their mineral oil counterparts. When making a motor oil from a mineral base oil, it’s nearly impossible to avoid potentially performance-limiting problems, especially oxidation sites. On the other hand, synthetic oils can almost entirely avoid introducing those oxidation sites, leading to a final product that lasts longer and performs better throughout its life. Rafe from Lubrication Expert has a great video on the topic:

I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to bring myself to go 25,000 miles without changing the oil, which synthetic manufacturers often advertise as being possible, but now I know what’s behind that claim, and that the cost of synthetics is at least justified by the amount of engineering that goes into them.

Final note: I’ve been using synethetics (only synthentics) for years starting with my last three new cars (Toyota Priuses). I was told by my dealer (whom I actually trust) and several mechanics that once you use synthetics you should NEVER go back to non-synethetic. Not sure how accurate this is, but thought I’d throw it into the discussion. Thanks.

I don’t have a source but I’m pretty sure this is one of those bits of “folklore” discussed in the article. There were some legitimate issues decades ago when synthetics first came out but they’ve been solved.

For a number years I owned and flew a Mooney M20C which has one of the most reliable reciprocating aviation engines built. During the 15 years I reached TBO on the original engine and replaced it with a factory new engine. With the original I ran Aeroshell 100 oil up until just before TBO and change out at which time I changed to Aero shell synthetic without any problem. The thing I noticed was that previously I had experienced consumption of one qt. between changes however none following the change to Aeroshell synthetic. As it turned out the general feeling amongst the experts was a higher flash point with the synthetic product. During the 15 yrs. I never experienced a single problem with either of the O360A1D engines running conventional or synthetic oils.

John B. McLaughlin 10122 Longford Drive. Knoxville, Tn. 37922. 865-385-3425.

I fully synthetic oil and its much better than traditional oil. If you must or have to use traditional oil in a pinch it will not hurt your engine. In the end oil is oil, its that synthetic oil is much higher quality. There is no good reason to use traditional oil after making a decision to change to full synthetic unless you find yourself in a pinch and need oil.

Agree that synths are a no brainer these days. I could run mineral oils in small engines above freezing but anything that goes below freezing => synth

I’ve also heard many say that when you begin using synthetic motor or gear oils, that you can never go back to petroleum based products. That may be true with many brands of synthetic oils, that are synthetic “blend” oil or “full” synthetic oil, but not going back to standard oils does not apply to all synthetic motor & gear oils.

The first in synthetics, with it’s high quality, can have standard API petroleum oil added to it, if it is absolutely needed on a vacation or trip. That can be done because the formulation of this synthetic oil can tolerate that.

When I began using synthetic oils over 20 years ago, my highway mileage went up by 5.2 MPG. With friction getting lowered by that much, this oil has saved me a lot of money by not getting fuel as often, less maintenance and my vehicles lasting longer. My truck has over 224,000 miles on it, has had no repair service, and runs the same as it did when it was new.

100% synthetic oil is the BEST!

I owned a 20 year old Yamaha FZS (Fazer) 600 with 100 000 km on its odo. And whenever I used synthetic oil I would need to refill between changes. When I switched to Mineral my trouble went away.

That’s odd. I have an 18 year old Yamaha R1 with 125,000 _miles_ on the odo. That has only ever been fed synthetic oil, and does not need a fill between oil changes.

And, I will also add that I change the oil at the interval recommended here in the UK which is (unaccountably) longer than in the US at 8000 miles.

The oil change difference may reflect a different expectation in the amount of dust that gets through the filter.

I’m in the southwestern US, and I think our last rainstorm was in October. The dust on my workshop floor has visible layers.

I had an early 80’s vintage Yamaha Maxim 650. It was a nice bike. I changed to synthetic in it, when it first came out. It sounded happier. I was happy until I took a trip on it and saw some odd smoke. When I pulled over I saw it was not in the exhaust but from the engine casing. I turned around right away. By the time I got back there was smoke billowing out of the entire engine and oil leaking out of the head gasket. I was a kid. Now I would be on the phone with the folks who made the oil, but back then I ate it.

There’s one famous brand synthetic, to keep HAD out of trouble I will call it “Facile Pun” … that is absolutely horrible for that sort of thing… put it in a motor and all of a sudden it’s got 6 leaks and the valvetrain sounds like it’s being attacked by a mad dwarf. Like you put water in the motor. 2 different motors a few years apart, first time it was a week or two developing the leaks, and I could hear the engine louder, I shortened that change interval and wondered if I got a bad batch… went back to running pennzoil and walmart brand synths in it. Few years later, walmart changed suppliers, booo, pennzoil never seemed to be on sale any more and price was always high, so found “facile pun” on sale again and gave it another shot… same but worse, sounded so bad, and started dripping on the driveway idling after I changed it… damn… I didn’t even like the idea of a trial run in case it really was starving the top end, or about to bust a gusher.. so sent a buddy out for replacement oil, changed it out right away… back to smooth running and “tolerable” leakage, which sealed itself up again maybe 2/3 weeks, half a quart later.

That would be the early days of Mobil-1. Conventional oil of the day had esters that would swell the engine seals and in those days Mobil-1 did not. So, if you switched from conventional oil to Mobil-1 those seals would shrink back and start to leak. An interesting part of the story is if you started with Mobil-1 you never had a leaking issue. This is because the seals never swelled so they never shrunk back and leaked with only Mobil-1 oil. Once the Engineers at Mobil Oil understood the issue, they added the required esters and life went on.

I ran Castrol GTX way back then – in my 1973 Cutlass Supreme. But once Mobil Oil corrected their birthing problem I ran their Mobil-1 products in all of my gasoline engines and I still run their products today,

Great comment! Funnily enough, this continues to be the case – because of the esters. It’s pretty common to see trucks fleets that have been running long oil drains on mineral oils start leaking when they switch to synthetic. This is because sludge and varnish that has built up over time is actually sealing leaks – but synthetics which contain esters and a decent amount of detergent solubilise (absorb) the sludge, exposing the leak points.

(PS I’m a lube oil consultant, formerly Mobil engineer – that was my video at the end of the article)

This was the noughties into the tens. I am thinking it’s what they had to take out between SJ spec and SM spec for emissions or something, older motors are all DO NOT WANT, I was running other synthetics fine. After that I was getting earlier S spec stuff, thinking they needed more zinc or something. I was passing emissions testing fine, 20-30% of allowed…. and below allowance for newest cars in etest program, which were around half what mine were.

This is what I came to say, in my experience an engine which has any tendency to burn oil will burn more synthetic versus conventional.

This isn’t a maybe in my experience, I’ve seen it over and over again in many different types of engines.

I have a 1979 Ford Bronco with a brand new engine And since I started the 1st time it used to consume a quart of oil every 5000 miles between oil changes Plus a lot of smoke every time I go downhill I tried all the top brands of synthetics in the market always the same it ended when I started using using Chevron havoline DS5W40 For me the best synthetic oil in the market I have been using it without any problems no more smoke no more consuming I used to be a fan of

mobile 1 But every time I use it I had engine noises on all my cars chevy Ford and Jeep always the same noisy engines I stop using it so the mobile 1 friends is not any good

Synthetic oils have additives that maintain and help cleaning the engine deposits. If you had no leaks that would indicate piston rings being cleaned up allowing oil into combustion chamber. Not all synthetics are the same. There is a large variety of class IV as well as V. Class IV is only slightly more expensive than crude oil but provides up to 10x of the protection comparing to conventional oil. I have not noticed any difference in IV & V unless it’s used in a dedicated track bike. I rode my GSXR 600 1k miles before turning into track bike and tortured for another 60k track miles. Replaced valves etc but pistons and crank were never touched. Never lost a drop of oil even though the average rpm would fall around 12k. All of that thanks to superior synthetic oils and proper maintenance.

I heard it’s got 3rd owner now and smoking oil at 80k miles. That wouldn’t happen if the bike was in my hands still. I’m a self thought mechanic owning couple of family wagons/suv sleepers with LS swaps and ‘69 El Camino with 454.

BTW- Older generations of Yamahas no matter the cc are bulletproof if maintained properly.

I started using synthetic 3 years ago went to the big box the price difference between 5 quarts of synthetic and 5 quarts of conventional in my usual brand was one dollar. Plus they didn’t have the viscosity I wanted in conventional. I figured if it costs about the same and protects better, might as well go for it.

Coincidentally, the Ziegler process can also produce octane from the same basic ingredients. The limiting factor to making green gasoline this way is having an economic and non-fossil source of ethane/ethylene.

CO2 to ethylene:

https://www.uc.edu/news/articles/2022/03/new-electrochemical-process-converts-pollution-into-ethylene.html

Careful, careful..

You don’t want to end in Saudi embassy.

Don’t be such a cut-up.

ouch…

truth.

I was a pump jockey at my brother’s Mobil station when Mobil 1 came out.

He went to a company sponsored demonstration of its capabilities, and it was an amazing improvement in temperature range, and wear protection.

But, the word was, (similar to what was mentioned above) after engine break-in, switch to synthetic, don’t switch back, and its thinner viscosity will leak where regular oils won’t, so don’t put in an older engine.

The engine in my Saab is amazing(ly bad). Mobil 1 is recommended with a required service interval of 5,000 miles unless you want to start making frappuccino in your engine.

I regularly drove 25k to 35 k kms with my 2,0t with mobil 1 5w-50 and never had any issues. drove about 150k kms with it until it started throwing the waterpump-, servo- and generator belt every time i hit a puddle.

I am 55 years old and similar to the author have been changing my own oil for 40 years. I was an early Adopter of synthetics due to the fact that I was, and still are, a big fan of Motorsports specifically road racing. I have lived 20min from road Atlanta for the last 40 years and can remember the first time a went to RA to attend a IMSA Camel GT race. I was lucky enough to score a pit pass and can remember talking with one of the mechanics on the Nissan GTP TEAM about what oil they used. When he told me synthetics I must admit I had no idea what he was talking about! Later when synthetics started to become more approachable $$ wise, I started using them in all my vehicles. To me, the small added expense is a small price to pay for the protection you receive especially in turbo applications where your oil takes a beating!

My 2003 GMC pickup had used synthetic since new. I have 145,000 miles on it. No oil use. And it will still smoke the tires if I want too.

My simi truck also uses synthetic blend I go 50,000 miles before oil change. Oil samples say I can go further but 50,000 a good number

Ernie

I remember reading when synthetic oil first came out that you couldn’t break in a new engine with it. Somebody took a brand new Ford engine, filled it with synthetic oil, and ran it for 500 hours. After that they tore it down, and the mill marks were still visible on the cylinder walls…

I had to do the heads on my 06 frontier last year. It’s just shy of 200,000 Km. The honing pattern was still visible on the (aluminum) cylinder walls. Synthetic since new.

If you mean the cross-hatching on the cylinder walls, you want that. Glassy-smooth isn’t a good thing. Those tiny scratches retain lubricants and prent excessive wear between the rings and walls. To the extent that better lubricants (synthetics) slow the wearing away of that, the engine will last longer (less burning of oil, better compression).

I have to say, I teach this stuff for a living (lubrication) and you’ve done an excellent job on this article. You hit many of the fine points that most folks miss or even don’t know about. Just wanted to let you know.

Thanks!

Your anecdote is great, I have always rented or borrowed so don’t get into the maintenance and long term wear side.

I feel like a constant-speed prop system creates an ideally suited wear environment not found in say a normal ICE-to-mechanical transmission environment.

That wear environment would still benefit form a lubrication idealized for the temperatures and pressures involved but it is probably as far away as possible in a piston ICE world from automotive or small gas engine wear environments most home/garage mechanics experience. Modern hybrids though can and probably do take advantage of an ideal RPM range to generate electricity for batteries and drive motors.

Of more interest to me is the exotic lubes, pressures, bearings, pressurized bushings, and wear patterns in jet turbines. The old J79 on the Phantom and almost everything with 1-2 seats back then was dripping all kinds of lube from every orifice.

I decided to put synthetic in my BMW k75 (as I am that guy that changes it way too late).

At the time I had a long ride home every weekend, that I did at a fixed speed with no traffic. The bike would run 215km+/-2km when the fuel light came on – reliable as clockwork.

After changing to synthetic it went 227km – just as reliably.

That’s 5% fuel saving, and even on a motor bike, that was way more saved than the cost of the synthetic oil.

While we’re all tossing in the rumours we’ve heard over the years, what about semi-synthetics?

The story I heard from a mechanic was that semi-synthetic was “worth a shot” at filling leaks in older engines. The way he explained it was that those oils had a wider variety of “molecule shapes and sizes” which would interlock and possibly seal things.

But I shy away from “Synthetic Blend”, I have yet to see what percentages are involved (not mentioned on the container). 5/95?

All I run is Motorcraft semi syn and due to covid the wife’s car sat all year and didn’t even have 3000 miles on it. Took it for a longish drive the other day and oil light started to flash at idle, changed out the oil and light went away. Car is 2001 Taurus with 190,000 miles. Also got a a 91 Ford with same engine but it has a flat tappet cam so it gets some zddp with the semi syn. The worst thing for the Ford Vulcan is not using a Motorcraft filter, it will rod knock on start up if the drain back valve doesn’t work MC filters are the only ones that will hold! Now there are fake MC filters since they switched from painted logo to sticker. I had to send in 4 filters to Ford since all were bogus knock offs! I’ve had the 180,000m 91 open and it was a nice clean motor no gunk or burnt oil anywhere, so I’ll stick with semi synthetic and genuine filters.

Be careful. A few years back, Casrtrol won a lawsuit that allows Group III base oils to be used under the label of “synthetic”. So not all “synthetic “ motor oils are produced with PAO.

If the vehicle in question has a turbo or a supercharger, use nothing but synthetic. However, if that’s not the case, regular oil works just fine. I recently retired my Pontiac with 262K on the clock. Nothing but cheap dinosaur oil went into it. Rust and a bad transmission did it in. Not an engine issue.

While walking my dog one evening, I complemented a man about the great condition of 3 “classic” vehicles he had parked out front of his house.

He said that after every oil change he would spray the used oil on the bottom side of each vehicle, decades later… no rust.

Nothing like contributing to the unwanted oil slicks on wet roads.

Wow, thanks so much for embedding my YouTube video! (I’m the Lubrication Explained guy). Your article is great! If anyone is interested, I did another video explaining “synthetics” vs synthetics. The legal definition and the chemical definition of synthetic are not the same: https://youtu.be/zpGJP0VmD-Q

Also, there’s an intermediate type of base oil called GTL (Gas to Liquid). You’ll sometimes see it marketed as Group III+, which is just to say that it has very good properties and performance-wise sits somewhere between a Group III and a PAO. https://youtu.be/zvmNE-f4lBE

Thanks for the links!

I haven’t changed my own oil in decades; the work’s easy, but since disposing of your waste oil by pouring it in the cracks of your driveway to kill weeds is no longer ecologically correct, and I no longer have my own driveway, I let my local car shop do that and check all the other things that need checking.

My current car requires synthetics – apparently most turbo-charged things do – and I’ve used synthetics with most cars I’ve owned since ~1990. While I also don’t believe they’ll go 25,000 miles on an oil change, it did mean that before the pandemic, if I slacked off on the 5000-mile oil change and it turned into 7-10, there was lots of cushion in there, unlike the Pennsoil I used to use in the 70s that would be black gunk by then.

I’ve used synthetic oil in every 4 cycle engine I own since 1985. What kills my vehicles today is road salt and other non engine lubrication related problems. I usually change oil every 8,000 miles or once per year, whichever comes first, I don’t think I have to be concerned about voiding the warranty doing this on my 1995 Ford Thunderbird 4.6 v8 with 105,000 miles or my wife’s 2000 300M with 58,000 miles

When i started racing we used the oil our sponsor would provide. We got about ten races out of a motor till the mains and rod bearings would ware thru the babbitt. New sponsor we we went to synthetic , what do you know almost 20 races till we saw the same damage. Also in our quick change rear end the temp was way cooler when we changed gears. Oh yeah my 03 toyota has 254000 and is still running strong.Stuff works !!

A discussion quite a few years ago at TCCOA (Thunderbird Cougar Club of America) suggested if you could not find a Motorcraft FL820S filter then the next best thing was Purolator.

Fun fact: You don’t have to change the oil in your engine. You do have to change the detergent that’s in that oil.

Back in the early days of automobiles, what you had to do every few thousand miles was an operation called “decoking.” This was essentially taking the engine apart and scrubbing carbon deposits off the inside of the cylinders and top of the pistons.

This, as you can imagine, was a gigantic pain in the ass.

Then somebody invented detergent bearing motor oil. You just had to swap that out and it kept all of the filth from building up in the engine.

The side effect of that is that you didn’t have to manufacture engines in such a way that it made them easy (or even feasible) to take apart for decoking. You could design them for much higher compression ratios and so on and so on.

It’s to the point now that as I type this, my computer complains that “decoking” is misspelled.

Another proof of the fact that it’s not the oil that you change is that there are now semi trucks that come with oil refining systems built-in. These separate the used detergent from the oil and replace it with fresh so that you don’t have to change the oil quite so often. These added systems are quite expensive, but pay for themselves in reduced downtime for the tractor.

I’m sure someone will disagree with me but I think it’s worth pointing out one problem with most, if not all synthetic oils. They work great in newer engines, I use them in all of mine now. They even work great in most older engines. However, if you happen to have an older engine with a flat tappet cam, you can’t use synthetics for break-in. Break in procedure on those engines have very specific lubrication requirements that no synthetic I’m aware of meet.

Once the cam and lifters on a flat tappet engine are broken in, my understanding is that the surfaces harden and are much less sensitive to lubrication requirements. Then you can use synthetics, conventional oils, or in the case of certain inline six engines plain water will probably suffice.

I’m aware that this only really applies to older engines and race applications, but since this site is sometimes about old technology, I figured it was worth pointing out.