You might have heard of the cochlear implant. It’s an electronic device also referred to as a neuroprosthesis, serving as a bionic replacement for the human ear. These implants have brought an improved sense of hearing to hundreds of thousands around the world.

However, the cochlear implant isn’t the only game in town. The auditory brain stem implant is another device that promises to bring a sense of sound to those without it, albeit by a different route.

Sensory Implants

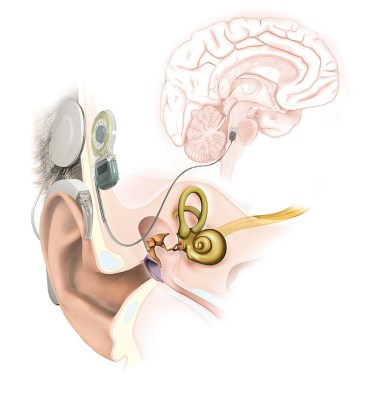

While the cochlear implant itself is a highly complicated device, the basic concept behind it is simple. The usual mechanics of the ear, which receive vibrations from the air and turn them into nerve signals, is bypassed entirely. Instead, a small electronic device captures sound with a microphone. The sound is then processed, with a priority on maximising perception of audible speech. This processed sound is used to drive an array of electrodes implanted within the cochlea itself. These electrodes stimulate the auditory nerves in the cochlea, enabling the wearer to perceive sound.

The auditory brain stem implant (ABI) is in many ways similar to the cochlear implant. The basic theory is indeed the same: audio is captured electronically, and then used to stimulate nerves to provide an auditory sense to the brain. Where the ABI differs is that it skips past the cochlea inside the ear entirely. Instead, the ABI stimulates electrodes placed in the cochlear nucleus of the brainstem itself.

The ABI thus has the benefit that it can provide an auditory sense to patients who, for whatever reason, cannot have a cochlear implant fitted to the auditory nerves in the inner ear. Patients with a condition called Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2) were initially the primary group for ABI use. NF2 is a condition that affects the nervous system, and its associated treatment often causes damage to the auditory nerve. Thus, for patients with this condition, an ABI is suitable where a traditional cochlear implant would be impractical. In cases where the auditory nerves in the cochlea may be damaged or destroyed, an ABI may be applicable.

However, the ABI comes with the drawback that it requires a far more complex implantation than a cochlear implant. Surgery involves opening the skull to access the brain stem, which is far more invasive than the simpler procedure required to implant a cochlear device in the inner ear.

Outcomes for patients are by and large not as successful as patients with cochlear implants when it comes to understanding speech either. With a combination of ABI use with lipreading techniques, many patients go on to learn to understand speech, but few can understand speech relying on an ABI alone.

This is largely down to electrode placement. The cochlea itself has a fairly straightforward map of areas that correspond to high and low tones, which can be stimulated in turn by an implant directly. However, when inserting electrodes into the brainstem, it’s harder to map out and stimulate these regions as accurately, and thus an ABI will struggle to deliver as much tonal information to the brain as a cochlear implant would.

The lower performance, more invasive implantation method, and obscure application of the ABI have meant that cochlear implants are far more commonly used in practice. Over 700,000 cochlear implants have been fitted worldwide. However, only a few thousand ABI devices have been implanted at most.

While the results from an ABI may not be up to the standards of a cochlear implant, these bionic devices still have value. For patients that can’t use a cochlear implant at all, an ABI still provides a basic auditory sense that can be useful, particularly when it comes to environmental sounds. Overall, it’s an interesting application of the same technology as the cochlear implant, but dialed in to a unique specific use case.

Bionic hearing indeed.

I suppose success or lack thereof is influenced by whether or not the patient had natural hearing prior to the need for the device.

When cochlear implants beame available in the eighties, the stories were about kids, and them hearing for the first time. In retrospect, some of the adaptation had to be simply learning to hear, rather than “adjusting to the imp!ant”.

Until a few months ago, I thought they were for those deaf from birth, or soon after. But they are available for adults, including those who had hearing but lost it. That suddenly made me think it may be easier for people who lost their hearing in the adaptation.

Cochlear implants is one way. It’s not reversible, so you lose hearing from other means. (Not an isdue since it’s already gone, but maybe an issue if there are new developments).

It’s harder for people with prior hearing, they have to go through training to learn how to hear with the implant. It’s been described as very different from normal hearing. It can take weeks / months to adapt, and not everyone does.

And we don’t really know what it sounds like. My grandson had a CI implanted at age nine months, after being born with the fairly well known genetic issue that leaves the hearing nerves disconnected from the cochlear membrane. Fourteen years later he hears quite well, plays piano and violin and composes, and in general clearly has some fine hearing including perfect pitch. (How perfect pitch works with only a small number of frequencies being fed to the brain I don’t pretend to know!)

So I think Mark is probably right about “very different”, but we don’t really know what it “sounds like”.

Do we really know that anyone’s senses are the same as each of our own though?

Work on the same laws of physics.

It’s much easier for people with prior hearing. The most successful category is the adults with the previous hearing experience. They need to learn to hear in a new way. People with no previous hearing have to learn:

1) how to hear

2) how to understand speech and sounds

But we’ll.never know, because even if you got one at an early age, then the other ear much later, you’d likely not remember.

I don’t think the training is different for adults.

All I know is that it’s been recommended that I get one, so I’ll hear from someone at some point. I am intrigued by it, but not sure I’d do it, especially not with the connector on the side of my head.

> maybe an issue if there are new developments

Without stimulation the area of the brain responsible for processing auditory input would be repurposed for other tasks.

Just as long as the advertisers [ or the Rick rollers ] don’t get their hands on it. Not to mention the company that maintains the tech going bust.

Still no doubt it’s a risk people are willing to take, considering what it can potentially provide. Although it must feel quite strange at first.

I wonder how far away we are from teasing apart and stimulating individual nerves in a nerve bundle. With only 13 contact points onto the surface of the brainstem it’s hardly a surprise that results are suboptimal. I guess if we ever get there it would have to be an automated process, a surgeon couldn’t make that many connections by hand.

Speech to text already exists and is getting better by the day. Paired with a Google glass type display would be a much, much better option than a craniotomy.

Humans get more information from hearing spoken words than just the words themselves, the way something is said: the inflection, the speed, the emphasis, even the volume (plus much much more) all impart meaning. We can identify the speaker (if we know them), we even hear people we care about more easily than strangers. All of that is supposing that these devices only help with hearing speech but hearing alarms, cars, shouts, a baby’s crying; none of them speech but all valuable in their own way.

Wow, I hadn’t heard of this yet. This is great to know, thanks for posting. As someone who just recently lost all hearing from one ear, I have mixed feelings about this. In the grand scheme of things I am quite fortunate, but I feel the loss of hearing acutely. Binaural hearing is a case where the whole is more than the sum of the parts. Pre-loss hearing from two ears was significantly more effective than the remaining single ear, even though the now-deaf ear was already degraded at least 10 dB prior to loss. Localization and source separation (the cocktail party effect) have disappeared. My tinnitus is much more severe now as well, as the brain seems to be cranking up the gain on the deaf side trying to hear anything at all, resulting in quite the cacophony, like tuning across AM radio. The nerve is most likely completely dead so a Cochlear implant is insufficient. The ABI discussed here should provide a path for at least some binaural hearing which would be amazing, and might also provide meaningful lessening of the tinnitus. But truth be told, as bad as my hearing is now, I don’t think its worth another craniotomy. I had a craniotomy six months ago to remove a “benign” middle-ear tumor called a vestibular schwannoma. The removal was successful, but my hearing nerve stopped working in the process, and I had the nasty complication of a Cerebrospinal fluid leak, which took several more surgeries to fix. All told I spent 3 days in the hospital for the original surgery and 21 days for the complications. If I did it again, I would need to have my head examined. God’s grace is sufficient for me. Let me know when there is an option based on external stimulation such as a micro TMS device.

Give me infra/ultrasonic hearing upgrade.

Also TOSLINK input.

This is fascinating. I was reading an article a long time back about patients that had visual interfaces setup in their brain to recieve signals from special image sensors that basically made up a camera for the brains of blind people. Intriguing was that patients who lost sight took very well to the implants and they soon were able to walk around and recognize shapes and objects and soon found it to be a low res replacement to the profound near total loss of visual sensory info their eyes used to provide.

However patients who were born with profound blindness did not take to the tech like the other patients with the article reporting most of those born without vision failed to be able to use it or found the experience very distressing and unpleasant and opted not to continue. I guess the visual processing parts of the brain need to be developed at birth, and if not used those parts of the brain will lack neural links to cognitive areas of the brain that allow for things like shape and object recognition and repetitive visual pattern or contrast recognition and depth perception/distance, fore/background sensing, etc … all of those things end up forming connections with other senses like touch and hearing for object recognition and avoiding things and range of motion using limbs, and every other aspect of life that interfaces with your vision in some way. After growing up without vision they felt that the visual signals were distracting to confusing or just as a unpleasant experience they found difficult to describe. Most felt that they were more proficient and capable without the implant than with it (which says a lot about the power of the mind and human development and our societies beliefs about people with disabilities or handicaps and their personal potential or capabilitues and what they can offer to society)

But yah I’m curious if the people who got the abi implants shared similar experiences as far as those born without hearing vs patients that became deaf later in life?

My son has an ABI and it was life-changing – it started as primarily a lip reading benefit, but now people he knows well, e.g., his wife and me, I’m happy to say, he doesn’t have to be looking at us. An article you might consider writing is in Europe there is a Med-El ABI that has a bunch of advantages, but they won’t go thru FDA for the few who need it, thus Americans have no access to this superior product.