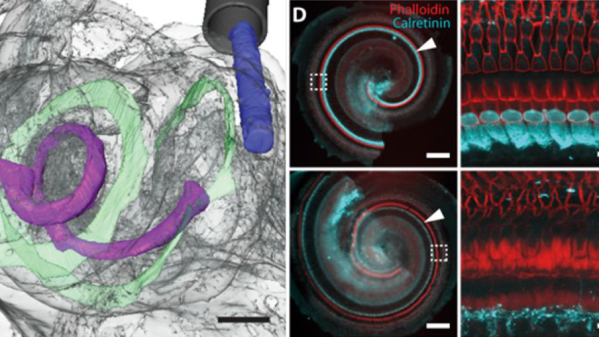

The cochlea is key to human hearing, and it plays an important role in our understanding of complex frequency content. The Visual Ear project aims to illustrate the cochlear mechanism as an educational tool.

The cochlea itself is the part of the ear that converts the pressure waves of sound into electrical signals for the brain. Different auditory frequencies excite different parts of the cochlea. The cells in the different parts of the cochlea then send signals to the brain corresponding to the sound it has picked up.

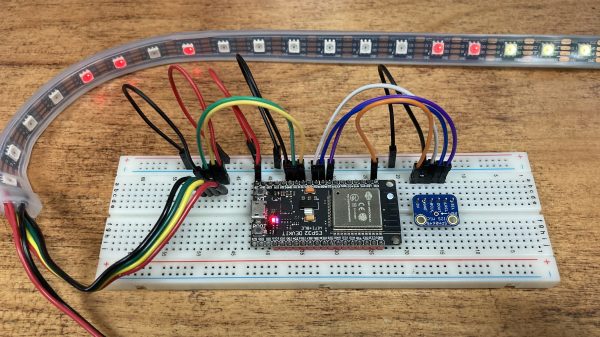

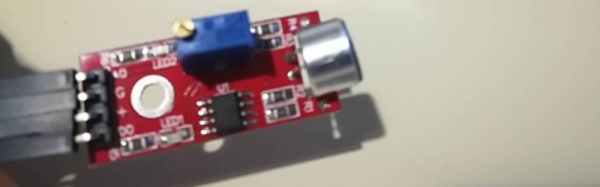

The Visual Ear demonstrates similar behavior on a strip of addressable LEDs. Lower LEDs coded in the red part of the color spectrum respond to low frequency audio. Higher LEDs step through yellow, green, and up to blue, and respond to the higher frequencies in turn. This is achieved at a high response rate with the use of a Teensy 4.0 running a Fast Fourier Transform on incoming audio, and then outputting signals to run a string of WS2812B LEDs. The result is a visual band display of 104 bands spanning 43 Hz up to 16,744 Hz, which covers most but not all of the human range of hearing.

It’s an impressive display, and one that makes a great music visualizer, too. When teaching the physics of human hearing and the cochlea, we can imagine such a tool would be quite useful.

Continue reading “Visual Ear Demonstrates How The Cochlea Works”