Tattoos are an interesting technology. They’re a way of marking patterns and designs on the skin that can last for years or decades. All this, despite the fact that our skin sloughs off on a regular basis!

As it turns out, tattoos actually have a deep and complex interaction with our immune system, which hold some of the secrets regarding their longevity. New research has unveiled more insight into how the body responds when we get inked up.

Not Going Anywhere

As we all know, if you draw something on your skin with a pen, paint, or marker, it will eventually come off in a few days or so. Tattoos, on the other hand, are far more longer lasting. The basic theory of tattooing is simple. Rather than putting ink on the epidermis (the upper layer of skin), it is instead inserted into the underlying upper dermis. There, the ink is free from the day-to-day sloughing off of skin. A properly-performed tattoo can last a lifetime, and beyond, in the case of the oldest identified tattooed individual from 3250 BC.

Normally, when foreign particles are introduced into the body, the immune system responds to destroy them. In the case of tattoos, though, the story is more interesting. As it turns out, our immune system does respond immediately when a tattoo is first inked. Cells swarm the damaged area of epidermis and dermis to try and deal with the invader. However, when these cells, called macrophages, interact with tattoo pigments, there’s a problem. The pigment particles cannot readily be broken down by the enzymes carried by the macrophage. Instead, the pigments remain stuck inside the macrophage until it eventually dies off and falls apart after a few days or weeks. Then, the pigment particle is ingested by another macrophage and the process begins again. Conveniently, just like skin, macrophages aren’t very opaque. This means we can still see the tattoo pigments even as they’re being swallowed and released over and over again.

Thankfully, macrophages don’t move around much at all, meaning that tattoos tend to stay where we put them. However, this process of death and reingestion is thought to be behind why tattoos tend to get a little fuzzy around the edges over time.

It’s also an important factor around how tattoo removal works. Laser tattoo removal treatments break down pigment particles into smaller pieces which can more readily be disposed of by macrophages. This process is why tattoo removal isn’t instant. Instead, the pigment particles are broken down into fragments, and macrophages in the skin then take a few weeks to remove the debris. This process is called phagocytosis, with the debris eventually making its way out of the dermis via the lymphatic system.

Some scientists are investigating whether temporarily inhibiting macrophage function could speed up tattoo removal. Normally, the lasers kill macrophages holding pigment particles, only for the pigment to be gobbled up by another macrophage shortly after. Instead, if the pigment was instead left exposed, it could be more easily broken down by the laser into smaller particles, ready to drain away via the lymphatic system.

Other research is ongoing as to the broader effects of tattoos on the immune system. Some studies have found that heavily-inked individuals actually have more antibodies circulating in the blood than those without tattoos. It’s led some to theorize that a tattoo could have a “priming” effect, acting as a long-term, low-level workout for the immune system. However, the immune system is complicated, and having more antibodies is not necessarily the same as having a more capable immune system. Research is ongoing as to what role tattoos could play in this area.

Perhaps most compelling, though, is that tattoo techniques could prove useful for interacting with our immune system more directly. Presently, most vaccines are injected deep into the muscle. Since these areas are not exposed to the outside world, the human body has very few immune cells in these areas. Thus, it can take time for the body to build an immune response to vaccines delivered via the intramuscular route. In comparison, the skin is full of immune cells as one of our first lines of defence.

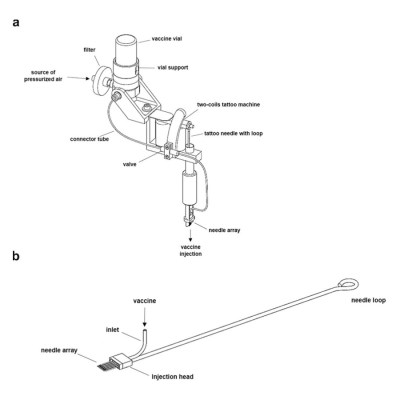

Providing vaccines with intradermal injections is possible, but current medical techniques in this area have some drawbacks. The techniques require significant training, and getting the injection wrong can spoil the effectiveness of the vaccine. However, tattoo techniques are all about reliably delivering material into the skin. Inspired by those techniques, researchers created their own tattoo-gun-like vaccine delivery system capable of making 100 microinjections in the skin per second. Early results have been good, using DNA vaccines for their ease of production. The hope is that a device can be developed to reliably deliver controlled vaccine doses intradermally, to generate a strong immune response quickly and efficiently.

Overall, as researchers learn more about tattoos, they’re learning more about the immune system and the human body as well. This knowledge may yet serve humanity well as we seek to tackle issues like autoimmune diseases and fight against difficult viruses and the threat of superbugs. In the meantime, next time you’re on the bench getting inked and you’re short on small talk, you can always have a great chat about macrophages with your friendly local tattoo artist.

Banner image: “Gogo Tattoo Machine” by Franki2001

oh that’s fascinating, thank you

Good job getting their “points” across. Plus tattooing as a replacement for dog-tags.

o_o what do you mean?

An idea.

https://www.militarytimes.com/off-duty/military-culture/2022/10/01/zelenskyy-to-russians-get-names-tattooed-so-we-can-id-your-corpses/

In I think Farmer in the Sky, Heinlein has medical information tattooed on immigrant’s bodies. Obviously very fine print. And you get to choose where.

Nothing about how long it would take to tattoo it.

yeah ngl I’m still struggling to understand your comment’s meaning. are you talking about the “tattoo = extra marker for authorities to identify someone” thing?

Excellent article, absolutely fascinating as Arya said.

I’ll get a tattoo saying I’m getting a drug that takes away my immune system.

They definitely interact with your personalty when you have to spend the rest of your life pretending you like them and got them that way on purpose.

Don’t most tattoo stories begin with; “One night, me and my friends were out drinking and …”

A little weird that the vaccine system is using a coil-style tattoo machine which tend to be a lot heavier and generally have a steeper learning curve compared rotary machines. The mechanics of tattoo machines are pretty fascinating on their own- from the electromagnetic drive of traditional iron-framed coil machine to various linkage designs that allow a rotary machine to deliver clean linear oscillation (and ideally some “give”) from a DC rotary motor to all manner of other mechanisms – pneumatic, swivel etc.

I’d expect coil-style was used to allow direct control over needle motion (velocity, depth, cycle rate, etc). A rotary machine has these locked in sync. Great when working with inks designed for the task, not so great when you’re also experimenting with a very nonstandard vaccine carrier that may have am optimum viscosity (and delivery depth) far from what a normal tattoo gun expects. .

I thought I remember reading about a “hypo-spray” style way of delivering vaccines, 20 years ago in Popular Science. The downsides were… not ideal. It turns out that blasting something through the skin over a larger area hurts more, and more chance for infection than a single needle.

Jet injectors were a thing. I got some vaccinations that way in the US Air Force in about 1987.

Jet injectors aren’t used any more because they have a high risk of transferring infections from one patient to another.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jet_injector

That is a shame since it does seem to have a lot of advantages.

You are looking for hacksaday, this is hackaday! As long as they deliver one hack a day they are on brand :) The rest is gravy.

LOL …. best comment of the week !!

I can heavily recommend looking into body and personal health hacking – this kind of stuff is seriously fun as background and as an example of how things work biologically

One of my kids is a tattoo artist. The machine pictured at the top of the article bares very little resemblance to what they actually use, it looks more like what they refer to as a home-made “prison machine”.

I’m not “inked” and never will be, but the article is interesting none-the-less.

You should look again. That is very much a real machine. The frame, yoke, front spring, contact screw, armature, needle bar, tube clamp, tube, grip and at least one coil are perfectly visible. The tattoo machine customization scene is massive, and many machines are modular and imminently hackable. A lot of artists customize and modify machines to their liking, whether that’s for comfort or aesthetic purposes.

Prison machines rarely, if ever, use coils. They typically use small DC motors, like those found in cassette players. Typically, the drive gear on the motor gets an offset hole, like a crankshaft. Magic markers (or other felt pens) are popular choices for grips/tubes, as they’re easy to get.

The machine in the photo bears little resemblance to a prison machine.

I did look at the pic again though and it still looks like a mess to me.

Believe me I know I’m no authority (and, honestly, don’t want to be) so I’ll defer to your expertise.

I thought it was a picture of someone holding a soldering iron a little too close to the tip.

Those particles end up in the lymph nodes. Nano-no no. Some pigments are suspect. More research needs to done for sure.

My smallpox vaccine was given in the skin. It was first spread onto the surface and then the skin was repeatedly scratched.

Intramuscular injections, unless they are particulate, get absorbed systemically very quickly, in some cases 30 seconds or so. It’s a viable route to administer most meds that usually are given IV (small molecules typically). I actually should look though, I do not know how absorption rates of, say, RNA injected IM are slowed. Or live or dead viral vaccines. To get around that though;

Vaccines are often co-administered with an adjuvant that intentionally hurts to prompt an inflammatory reaction at the site and potentiate the immune reactive to vaccine components. That’s why your arm hurts for a few days after. Not the needle trauma itself.

Also as mentioned above somewhere, transdermal delivery was tried and given up on because of no great way to sterilize the special equipment necessary to deliver it, not because it was an inferior method per se. The only transdermal med we use is local anesthesia for needle punctures, ironically.

Good on researchers exploring other options but a dirt cheap, sterile and disposable needle in the arm is going to be really hard to best.

It’s only intramuscular if it is asperated. Un asperated is intra, whatever the needle ends up in.

A regular old needle can do subcutaneous too.

If running a clinic in a jungle is anything like running a home kitchen according to Alton Brown, you should avoid any tools that only have one job. Unfortunately, I don’t think the two are anything alike.

Vaccinating people with a tattoo gun? Sounds like a hack to me.

Your first line of defence is your innate immune system, so don’t go hurting your body naively believing there is any benefit to tattoos at all.

Tattoo artist Sailor Jerry gave himself his cancer medicine with a tattoo machine.

How about you let us professional tattoo artist help out instead of training medical students to figure the way…i mean we can teach them how to use and an deliver it properly, and to be honest a percentage of us tattoo artist we have some type of medical background. Also please dont call it a GUN…its a Tattoo Machine…and for the ones doing this 2 things

1. Use a Rotary like example Bishop Rotary machines…coil might scare the patients with the souns

2.having the vaccine distribution straight directly like that diagram is bad…reason why we dont fill up ink like that you will over flow it and then you make a mess and loss product for over filling and making a pool that you going to uave to wipe off. Last time i check we dont wanna be wasting vaccine like that.

Get a Pro tattoo artist involve please, great idea but you need the right ppl to help in the tattoo idea side

I think I’d want a 2 in 1 ie a mixture of vaccine and pigment in the tatoo machine and then create a design on the skin such as skull and xbones, preferably not in the middle of forehead.

I think I’d demand an MSDS safety sheet breakdown of what exactly is in something about to be permanently injected under my skin. Tattooists presumably supply this information upon request, no?

According to this paper the EU and the FDA have not approved ANY inks for tattoo use: https://sci-hub.wf/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125667

You may be able to get an MSDS but it would depend on the tattoo shop being honest about where their inks are sourced (anecdotally, tattooists often use automotive pigments because they have good availability and consistency across batches… although again, NOT approved for dermal use!)

Note from the above paper that several heavy metals and toxic compounds were detected in the tattoo pigments analysed.

A normal injection for vaccination normally does not hurt, of course depending on the skill of the doctor or nurse who gives it. Tattoos are said to hurt while administered and for some time after because they have much more area of skin affected. I do not have one, but I prefer a vaccination which does not hurt.

I’d say that conventional injections do hurt, not unbearably, but similar to jabbing yourself on a pin or a thorn etc. Depending on the injection it can be sore for a few days afterwards too.

I do agree that tattoo’s hurt more though. For me, a line being drawn felt like being cut with a scalpel (which I’m also familiar with), although most of the pain went away as soon as the tattoo gun stopped, replaced by a dull ache, which went away after a day or so.

The skill of the person administering the injection makes all the difference, which is why I’d much rather see a nurse than a doctor. They tend to get a lot more practice and are usually good at it.

Inovio Pharmaceuticals invented the Cellectra injection device for just this purpose. https://inovio.com/dna-medicines-technology/

Do you think tattoos just disappear in a week or something? My grandfather had 50+ year old tattoos that were there at his funeral. Or that our skin just stays on permanently? Have you ever scrubbed in the shower? Both can and do occur and have been for centuries. The article provides a great explanation of how tattoos work but it seems to have still gone over your head.

I’m more interested in the applications of active “inks”. Imagine being able to “print” circuitry into your skin including solar cells batteries and even active elements like LED’s, computation and RF transmission… Sure there’s currently a lot of technical hurdles to overcome but there are already a number of large strides in the right direction.