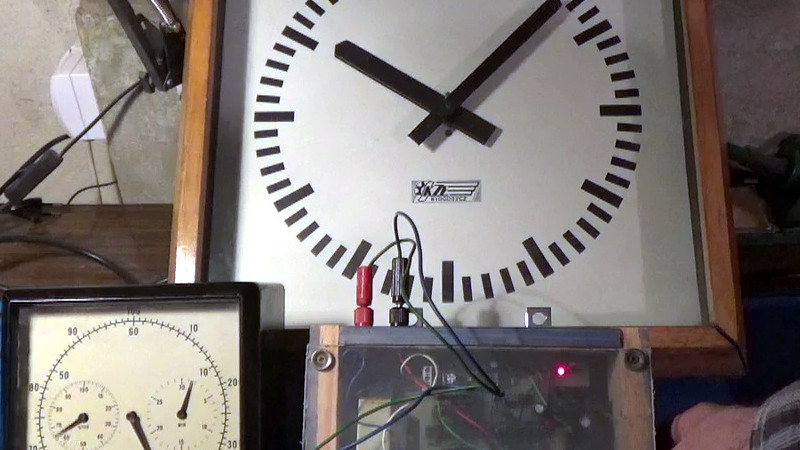

Making an electronic clock is pretty easy here in 2023, with a microcontroller capable of delivering as many quartz-disciplined pulses as you’d like available for pennies. But how did engineers generate a timebase back in the old days, and how would you do it today? It’s a question [bicyclesonthemoon] is answering, with a driver for a former railway station clock.

The clock has a mechanism that expects pulses every minute, a +24V pulse on even minutes, and a -24V pulse on odd ones. He received a driver module with it, but for his own reasons wanted a controller without a microcontroller. He also wanted the timebase to be derived from the mains frequency. The result is a delve back into 1970s technology, and the type of project that’s now a pretty rare sight. Using a mixture of 4000 series logic and a few of the ubiquitous 555s [bicyclesonthemoon] recovers 50Hz pulses from the AC, and divides them down to 1 pulse per minute, before splitting into odd and even minutes to drive a pair of relays which in turn drive the clock. We like it, a lot.

Mains-locked clocks are less common than they used to be, but they’re still a thing. Do you still wake up to one?

Could have used, oh, never mind.

This guy tinkers

Neon lamps.

Not quite the same thing, but several years ago I converted a fairly prominent pulse clock to use MSF time (so that it automatically handles summer time).

https://bodgesoc.blogspot.com/2015/09/clock.html

That had previously been converted using a mains-synchronous 1rpm motor with a cam that operated a

microswitch to generate the pulses.

The same could have been done here, using 1890s technology, but would have required a 0.5rpm motor to generate the alternating pulses, presumably.

The interesting part of the project that I undertook was having a design goal that the mechanism should run for 50 years or so, which led to the choice of a simple linear PSU amongst other things.

I found my (mains-locked) alarm clock showing 6:58 when the news started this morning, advanced it to 7:00, watched my phone, which also showed 6:58. Turns out they started the news two minutes early.

Actually, clocks used in news stations are far more precise than anything civilian can buy so probably your stuff was off.

Except mobile phones are locked to the time distributed via the phone network towers which are rubidium locked and synchronised via NTP.

And the mains frequency has very strict giudelines on how much the frequency deviates from ideal per day.

It’s unlikely that two clockes referenced to those two sources would be simultaneously out.

More likely the caffeine-starved programme scheduler in the TV studio pressed the go button too early.

The time error correction works by setting the target frequency between +/- 0.1 Hz of the nominal depending on the direction of the error, so if the grid has been running slow for half a day, the maximum error you get is +/- 1.4 minutes. Then it’s supposed to be corrected back.

Renewable energy on the grid makes it harder to keep within the TEC limits because it’s not dispatchable, so you can’t add or remove power to hitch the frequency up or down as you please.

The Dutch “NPO” (National Public Broadcaster) removed their pips a few years ago and now starts the news.at the time they please, usually on the top of the hour but sometimes a few minutes earlier or later (so they don’t conflict with sports events, major speeches etc). The start of the news is no longer a reliable time source, ai had witnessed a few tens of seconds late, but never more than a minute early wjen no special event was going on.

Yes, having accurate time available and using it are two different things.

You can see the current UK mains frequency here:

https://www.gridwatch.templar.co.uk

(And also the mix from various energy sources)

Cool !

Jenny,

Using the ac mains as a timebase is a technique approaching its centenary. Having a master clock that emitted current pulses to a series of electromagnetic relay slave clocks was one way to keep all clocks around a large factory or office building synchronised.

However, now that we have high accuracy, high frequency, quartz stabilised oscillators, we can turn the technology around to snoop on the accuracy of the ac mains frequency.

As you know, UK mains has a nominal 50Hz frequency – but it varies throughout the day and according to how much load is currently on the National Grid. Grid frequency is a good indicator of the state of the grid, whether heavily loaded, lightly loaded, or when large generators are switched in and out of the grid.

Some years ago I built a grid frequency monitor with a Microchip PIC16F628 which timed the interval between the zero-crossings. After some filtering, these average interval timings were sent out via the UART, to a PC where they could be plotted.

The results were fascinating, and not always complied with the stated frequency limits published by the National Grid Company!

I suspect a time will come, in the not too distant future where synchronous time is deemed unnecessary. I believe that the US have already stopped the same number of cycles every day rule. Other operators will follow I’m sure. Using zero crossings to get 100Hz is also a test of how harmonic free the supply is. An embedded harmonic can quite easily cause multiple zero crossings around the real one.

I saw somewhere that if you can hear the 50hz/60hz hum in the background of a video recording, you can match its discrepancy to recorded values and know exactly what time it is in the video.

Tom Scott made a video about ENF analysis a while back, perhaps you saw it there! If not, definitely watch the vid.

Economical quartz crystals that aren’t in ovens don’t often have 1 PPM accuracy. That means they’re off by more than half a minute a year. 1 PPM is an error of 4.32 cycles/day at 50 Hz.

Just use radio-controlled clocks..

They’re more accurate than anything else, in general.

“He also wanted the timebase to be derived from the mains frequency.”

That’s a good idea as long as accuracy is not a priority. “Today, AC power network operators regulate the daily average frequency so that clocks stay within a few seconds of the correct time. In practice the nominal frequency is raised or lowered by a specific percentage to maintain synchronization. Over the course of a day, the average frequency is maintained at a nominal value within a few hundred parts per million.”[1]

1. Utility Frequency

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utility_frequency

2. 60 Hz AC Mains Frequency Accuracy Measurement

http://www.leapsecond.com/pages/mains/

If a clock is less than 1 minute off after half year that’s enough in most cases because the time has to be readjusted anyway because of DST.