For people who have lost the ability to speak, the future may include brain implants that bring that ability back. But could these brain implants also allow them to sing? Researchers believe that, all in all, it’s just another brick in the wall.

In a new study published in PLOS Biology, twenty-nine people who were already being monitored for epileptic seizures participated via a postage stamp-sized array of electrodes implanted directly on the surface of their brains. As the participants were exposed to Pink Floyd’s Another Brick In the Wall, Part 1, the researchers gathered data from several areas of the brain, each attuned to a different musical element such as harmony, rhythm, and so on. Then the researchers used machine learning to reconstruct the audio heard by the participants using their brainwaves.

First, an AI model looked at the data generated from the brains’ responses to components of the song, like the changes in rhythm, pitch, and tone. Then a second model rejiggered the piecemeal song and estimated the sounds heard by the patients. Of the seven audio samples published in the study results, we think #3 sounds the most like the song. It’s kind of creepy but ultimately very cool. What do you think?

Another cool aspect is that this revealed which parts of the brain respond to what when listening to music. While many of us might assume it all goes on in the auditory cortex, some audio such as the onset of voices and synthesizers is processed just behind and above the ear in the superior temporal gyrus. Even though this study focused on recreating music, the researchers believe this will move the idea of the speech brain implant forward.

Why Pink Floyd? While the researchers admit to a fondness for the band, the song they chose is layered and complex, which makes for interesting analysis. Although we are not sheep, we would have to agree.

It’s a bit of a magic trick, to be honest. They play a song, then record the brain waves, then record the brain waves and play back pieces of the song that correspond to those brainwaves. Of course it’s going to sound something like the original song.

Note: they’re not playing what was recorded from the brain, but what the AI model is guessing the person is hearing. You could put the model to work on someone else’s brain, who has never heard the song, and the model would still produce something that resembles “Another brick in a wall”.

I would be surprised if the model suddenly started playing Abba’s “Money money money”, reconstructed out of pieces of the Pink Floyd song.

That would only happen if they played ‘Pink Floyd – Money’ instead of ‘Another brick in the wall’

It would be interesting to run different interpretations of the same music through this procedure and compare the results, like Pink Floyd’s Dark side of the moon and Easy Star All Stars’ Dub side of the moon.

I miss Mike Szczys …. Wish You Were Here.

Szczys you were here.

Yep. Slippery slop.

Interesting. But…. parts of the methodology in this experiment irritate me.

“Pink Floyd?” Really? Nothin’ against pink, but if the study was about “all genres” of music (I think that’s the term they used) wouldn’t it have made more sense to compartmentalize the experiment to African or American-Indian drums (rhythm), barbershop quartet (harmony), opera soloists (melody) and so forth, studying these separately before jumping right to Floyd?

Or could it be that the AI-reconstructed music always sounds like psychedelic organ, and by choosing to make Pink Floyd the source, the researchers can then claim to have regenerated “identifiable” music?

The latter would certainly improve the odds of receiving additional grants to continue this work, wouldn’t it?

There is always one.

Let us know how your experiments go in the genre of music you prefer.

My concern is design-of-experiment methodology, and whether or not the the approach applied here was ultimately self-serving. Clearly you didn’t grasp that because, most likely, you didn’t bother to read past my second sentence before being triggered. So, let me try again:

As different parts of the brain process different aspects of “music,” it would make sense to explore those separately, to the extent possible, before jumping into something (comparatively) more complex like a Pink Floyd tune. It’s like trying to understand the import of a polynomial with 12 variables vs an expression with only two.

I’m willing to bet that if they’d limited the initial exploration to rhythm/beats, for example, that an AI reconstruction might actually regenerate a recognizable pattern. Instead, what we have here is something that might be more cool (it certainly checks all the buzzword boxes to generate seed money, like “AI” and “neural”), but something of unclear academic value.

From looking at the references in the paper, a number of those simpler/more limited experiments have already been carried out. I think it’s fair to investigate more complex music processing at this point; whether prog rock (as a mix of Western harmonies, African-derived rhythms, et c) was chosen for its intrinsic qualities or for its charisma when presented to the public and/or grant committees doesn’t seem to matter much.

I wonder what results they would get if they let people listen to the song several times and then recorded the date when they were remembering the song.

Just for laughs, while they had the volunteers wired up, they should have had them *imagine* hearing the tune, w/o actually playing it into their ears.

I think “another brick in the wall, part 2” was chosen for sentence

We don’t need no thought control

in the lyrics of the song.

It was part 1 that they used for the experiment, though

One of the most startling things about aphasia is the several historical cases in which a person lost the ability to talk, but not to sing. Singing perhaps switched enough circuits in the brain to make the thing work again, but talking in normal cadence and pitch was impossible. Iirc there’s even a case of a person who could still communicate by adding sing-song pitch and rhythm to what they wanted to say, while others were only able to recite preexisting songs they had memorized.

Similar things have happened in cases of brain damage causing extreme loss of manual dexterity, yet things like playing the guitar still somehow worked if they were already a practiced guitarist. Ask them to type on a keyboard or use a pair of nail clippers and it was impossible.

Or maybe these were anecdotal frauds, malingering, or even physicians exaggerating for acclaim.

The human brain, man. That’s the final frontier. We won’t figure it out to a satisfying level of completion for a very long time. We know so much more than we did a little while ago, but we still have a very long way to go.

Source(s) cited: I made it all up

This was a wasted opportunity.

Effectiveness should have been measured in air guitar minutes.

AC/DC would have been a much better choice.

Layered, pffft says Rush.

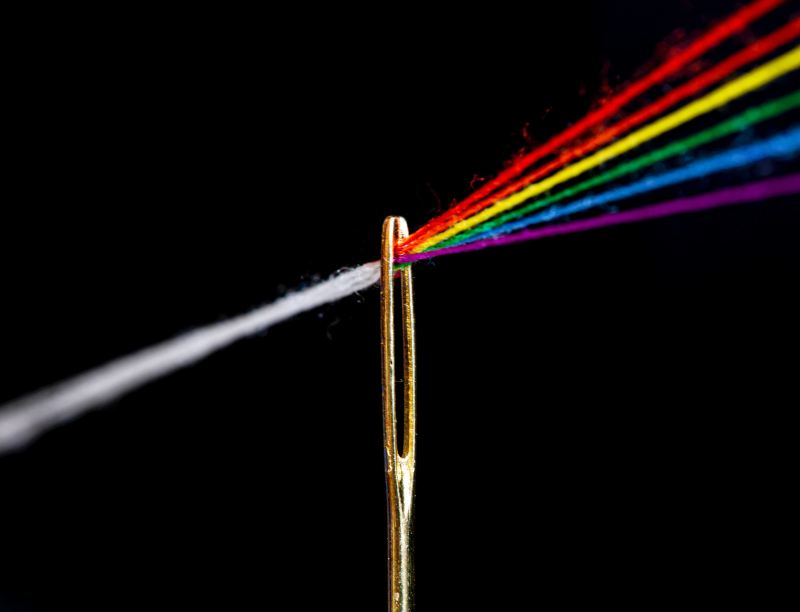

The title pic is cool!