When motion pictures came along as a major medium in the 1920s or so, it didn’t take long for corporations to recognize their power and start producing promotional pieces. A lot of them are of the “march of progress” genre, featuring swarms of workers happy in their labors and creating the future with their bare hands. If we’re being honest, a lot of it is hard to watch, but “Master Hands,” which shows the creation of cars in the 1930s, is somehow more palatable, mostly because it’s mercifully free of the flowery narration that usually accompanies such flicks.

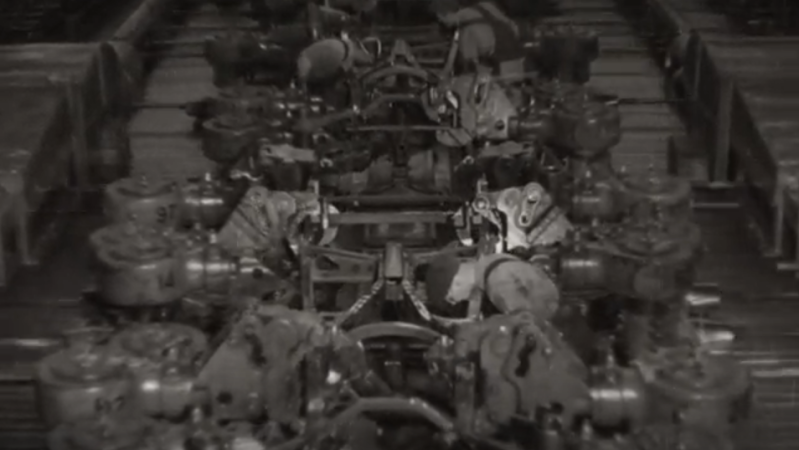

“Master Hands” was produced in 1936 and focuses on the incredibly labor-intensive process of turning out cars, which appear to be the Chevrolet Master Deluxe, likely the 1937 model year thanks to its independent front suspension. The film is set at General Motors’ Flint Assembly plant in Flint, Michigan, and shows the entire manufacturing process from start to finish. And by start, we mean start; the film begins with the meticulous work of master toolmakers creating the dies and molds needed for forging and casting every part of the car. The mold makers and foundrymen come next, lighting their massive furnaces and packing the countless sand molds needed for casting parts. Gigantic presses stamp out everything from wheels to frame rails to body panels, before everything comes together at the end of the line in a delicate ballet of steel and men.

The whole process is fascinating, not least because it shows just how little cars have changed in 88 years. Health and safety standards have changed, of course. How close the workers were allowed to come to machines that could easily turn them to pulp is amazing, especially on the frame assembly line; a worker standing just a few inches out of place would have a very bad day when those giant riveting machines swing in to attach cross-members to the frame rails. It also appears to be very dark in the plant, which is in marked contrast to the brightly lit assembly floors of today’s auto plants. Also of note is just how vertically integrated the process was, as it looks like literally every part of the car was made in the Flint factory, and just as it was needed.

While this film is ostensibly about building cars, as the name suggests it’s more a celebration of the craftsmanship that made the whole process work. There are a lot of close-ups on the hands of these workers, most probably long dead now, engaged in work that’s in turn delicate and brutal. There’s also a lot to be said about the engineering that went into the assembly line itself; coordinating a process spread out over such a vast area and getting all the people and parts into the right place at the right time without the aid of modern control systems is just mind-boggling.

It looks darker because film was not yet as sensitive as it was at the end.

I thought so too.

Is there any way to guesstimate/calculate the actual brightness in that place?

Maybe something along the lines of knowing the films chemistry and age + shining calibrated light sources through it and measuring the dampening of different wavelengths (I assume it’s non-linear)?

And possibly applying the appropriate corrections to the digitalized copy of the original?

You can’t really determine that, but you can try and find quantitative data on lighting regulations (and practices) from the 20s and 30s in old lighting industry journals and tech papers, which you can find here: http://lamptech.co.uk/Literature.htm

I absolutely love it!

Sometimes the lighting journal compares the pre-war and the post-war situation both with measurements and pictures. Of course it’s very much advertising the virtues of the manufacturer’s shiny new light bulbs, but it does help with getting a feel of the actual factory conditions. Making a movie in those conditions exacerbates the dimness of the light, because the things you make a film of, are always lit with a film spotlight which makes the subject stand out very brightly, while the rest appears almost black. The film’s exposure latitude was way less than that of the human eye.

Back in the 1930s, all the factory lighting was still incandescent, mostly with workplace-only lamps and a handful of high bay bright ones that only lit the whole floor somewhat dimly.

It was only in the early and later, that high bay, high intensity mercury vapor lamps were introduced, that could actually brightly light up a floor (though in a ghastly blueish-green hue). And only in the 2nd half of the 30s did they invent the more expensive phosphor-activated high pressure mercury lamps that gave a ghostly white light.

Finally figure what they used on the Titanic. Maybe it was GE (we bring good things to light).

That and of course they couldn’t bring in so many lighting rigs as they would use on a film set – it was live, running production line. If one filmed today’s factory using an old film camera it would likely look very similar.

Kodak 1217 film had just been introduced a couple of years before, and Kodak was given an Academy Award for technical achievement for the astounding for that time sensitivity of that film. It had the equivalent speed of iso 32.

https://rec.arts.movies.tech.narkive.com/Xyp0iO6c/eastman-and-dupont-win-academy-award-in-1931-for-super-sensitive-panchromatic-film

Compare that to 12,768 for the iPhone 14 Pro.

So at the time a point that was so obvious that it didn’t need stating was: You won’t believe where we were able to make a movie. It was an extreme technological flex for the time.

um, dude, why was there a need to mention they’re like…dead?

There are a lot of close-ups on the hands of these workers, most probably long dead now, engaged in work that’s in turn delicate and brutal.

What’s wrong with mentioning it? It gives a sense of time and perspective.

Why not? Are you superstitious or something

Dead but not entirely gone,due to our relenless need to consume and coment on media.

It’s amazing to me how fast these guys work. Young folk nowadays appear to move in slow motion when they’re on the clock.

>Young folk nowadays appear to move in slow motion when they’re on the clock.

As they should. Hard work only gets you more hard work. No point in wearing yourself down for a corporation.

Think they might know they’re on camera?

It would be fascinating to juxtapose this against a modern assembly line.

Hackaday posters/readers finally clued -in to what is happening with some software UPGRADES?

“NSA purposely infiltrates some software companies to damage their products to prevent use by NSA’s perceived enemies of the US.

NSA planted agents in Forth standards committees to damage figForth, we discovered at Sandia National Laboratories. ”

There are no advantages to the ‘upgrades’ to figForth … and lots of disadvantages.”

NSA deserves reprimand?

Albert Gore willing, of course.