The Universal Serial Bus. The one bus to rule them all. It brought peace and stability to the world of computer peripherals. No more would Apple and PC users have to buy their own special keyboards, mice, and printers. No more would computers sprout different ports for different types of hardware. USB was fast enough and good enough for just about everything you’d ever want to plug in to a computer.

We mostly think of USB devices as being plug-and-play; that you can just hook them up and they’ll work as intended. Fiddle around around with some edge cases, though, and you might quickly learn that’s not the case. That’s just what I found when I started running complicated livestreams from a laptop…

Fool To Try

When I’m not writing 5,000 words a day as the most forgettable journalist online, I’m running a musical livestream on Twitch. I invented Drumbeats and Dicerolls— a show in which I roll dice in order to write music in Ableton Live. The dice choose the instruments and sometimes even the notes, and then it’s up to me to turn all that into a coherent song.

The concept is simple enough, but on the technical side, it gets a little complicated. Video-wise, I use two webcams—one for me, one to film the dice as I roll them. That’s two USB devices right there. Then I have my mouse and keyboard, both running via a single Logitech wireless dongle. Finally, I have my Steinberg UR22 audio interface—basically a soundcard in an external box that has musician-friendly hookups for professional-grade mics and speakers.

It all adds up to four USB devices in total, all with USB-A ports. That doesn’t sound like much. Only, since my desktop was stolen, I only have a laptop to run the whole show. That presented an immediate hurdle, as my laptop only has two USB-A ports on board, plus a USB-C port on the rear.

I figured I’d hook up a USB-C hub with a few extra ports, and along with my monitor’s additional USB hub, I’d be all good. Trouble struck as I first attempted to stream in this way. Both webcams worked, with one of them even running through a separate NVIDIA Broadcast tool to do some background removal. However, the audio was problematic. Every ten to twenty seconds or so, the sound would drop out or stutter. It was incredibly jarring for a music stream.

Not So Simple

I was frustrated. This was a problem I’d never had before. In normal life, I’d always just plugged whatever device into whatever USB port with no problems. Even when I’d chained hubs off hubs, I’d seen little issue, even with high-bandwidth devices like HD webcams or portable hard drives. And yet, here I stood. I was plugging, but the gear wasn’t playing.

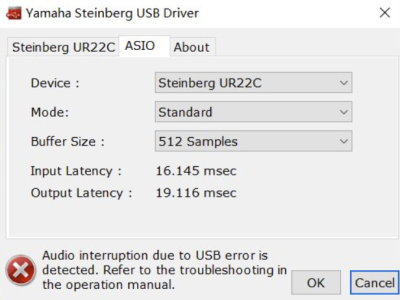

At first, I figured I just had to tweak my software setup. I was using the Steinberg UR-22 via the Windows Wave drivers in Ableton. I figured if I just used the professional-grade ASIO sound driver instead, my stuttering problem would go away. However, then I found that my streaming software couldn’t naturally capture audio from this device. This necessitated pulling in the Reastream plugin to truck audio from Ableton into Streamlabs, but that wasn’t so hard. I tried a test recording offline, and it all worked great. No stutters, no problems. Only, as soon as I tried streaming live… the stuttering was back, in a big way.

For my second stream, I switched things up. I ended up using a USB headset plugged right into my laptop’s native ports for audio, back with the Windows drivers, and kept the Steinberg UR-22 just for recording vocals into the machine. This worked great, with no stuttering on playback. But I had a new problem—only one of my webcams would work at a time. Oh, and the mic feed from the Steinberg was dropping out randomly, ruining my vocal recordings.

Looking at the mess of cables and daisy-chained hubs in front of me, I realized I had to simplify. I put the Steinberg device on the most direct hookup, straight to the laptop’s USB-A port, and set it back up in ASIO mode. Then I connected both webcams to a Lenovo docking station, hooked up by USB-C. I eliminated any extra hubs, ditched the USB headset, and had the most critical device—the Steinberg—connected by a single cable. This had to solve it, right?

Well, the webcams were now humming along nicely, probably because they now had enough power from the docking station instead of an unpowered hub. But were all the problems fixed? Alas, no. Try as I might, the Steinberg device would stutter every few seconds or so. I double-checked that I didn’t have a CPU, RAM, or hard drive issue—everything came back clear. But for some reason, two webcams and an ASIO device was making the audio choke.

Brick Walls

Hours more troubleshooting rushed by. After all this, I’ve come to findings that confound me as an engineer. I can run two HD webcams and a USB headset with no dropouts, just using basic Windows audio drivers. And yet, trying to use the Steinberg audio interface, it just falters. Even with the webcams degraded to ultra low resolution! This interface has seen me through thick and thin, but it just won’t work under these conditions. Despite the fact it’s using the same sample rate as the USB headset, and should surely be using a similar amount of bandwidth. Regardless, its driver tells me there’s a USB problem and I can’t seem to solve it.

The one thing that itches my brain is that the stuttering seems to only happen when I’m streaming live online. When I’m not streaming video, the Steinberg happily operates as rock-solid as the cheap headset. The thing is, my network connection is via a PCI-Express WiFi chip baked into the laptop, so… that’s not even a USB thing.

When I started writing this a week ago, I thought I’d have solved it by now. I’d have a nice clear answer about what went wrong and how I figured it all out. That didn’t come to pass. Part of me wants to rush out and build a desktop PC with a real amount of ports to see if eliminating hubs and nonsense solves my problems. The other part of me wants to redouble my efforts to track down the issue with every last USB inspection utility out there. I’ll probably do the latter and update this article in due course.

Instead of a neat solution, all I’m left with is confusion and a cautionary tale. Just because you can plug a bunch of USB devices together, it doesn’t mean they’ll all work properly and play nicely together. Our computers are more complicated than we expect, it’s just they’re better at hiding it from us these days.

The Update

Would you believe, the comment section here did just what I hoped? It helped me solve the issue!

The clue was in the text above, I just hadn’t gotten my thoughts in the right order. Several people noted that I had explained there were zero audio dropouts when using two webcams and the Steinberg audio interface when screen recording. The problem only occurred when I was livestreaming to Twitch.tv. Did it have something to do with network traffic?

Indeed it did. In fact, I soon found out my laptop had another oddball performance issue. When uploading a large file online, my laptop would stutter even just playing back a simple video file stored on disk. It seems for whatever reason, heavy WiFi traffic brings my laptop to a standstill and affects the USB interface too.

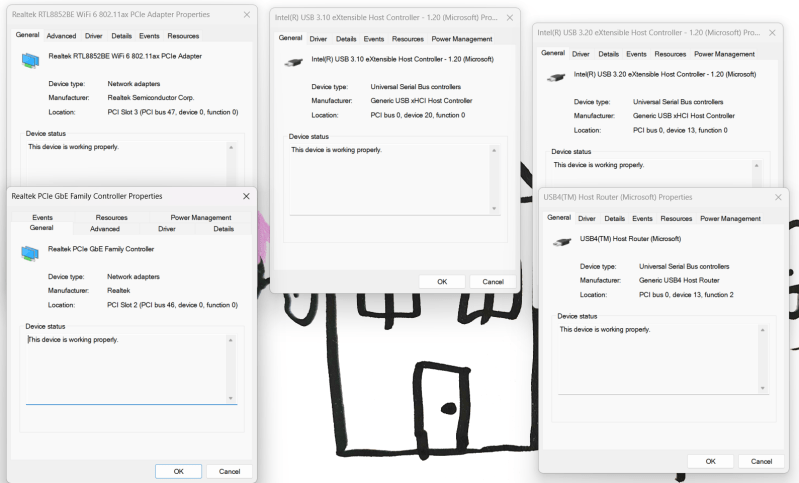

This makes little sense to me. I flipped through Device Manager, and found that the WiFi adapter was connected via the laptop’s PCI interface, just like the Ethernet adapter. And yet, for whatever reason, I can stream just fine with my audio interface and two webcams as long as I have a wired network connection.

Maybe the problem wasn’t USB at all, and just presenting that way. I’m still trying to uncover the root cause, because I’m not sure why WiFi would affect the USB interface, and, indeed, one audio device more than another. Regardless, I got my solution with the aid of the Hackaday community, and for that, I am grateful.

Regarding the webcams, IIRC some don’t down sample on the device but always stream full data and let the software resample the selected dimensions so there is no effect/release of the bandwidth

Good insight. Seems like that may be a pointless tweak…

Have you tried a wired ethernet connection? I get a lot of audio glitches when using Teams over WIFI

good Idea but @”Lewin Day”: Using a public HaD article for your personal error diagnostics support???

Once commenters help him find the solution, it should be a very useful article.

Look in device manager to see how things are really hooked up. Your Wifi may actually be going over USB.

Yeah, saying “this is plugged into this port and a hub and then this” doesn’t actually help with USB. If I plug a device into the Thunderbolt dock off my laptop, it actually ends up being 3 hubs deep, so at a depth of 4 (R->H->H->H->device) already.

I’m sure there’s a Windows equivalent of the USB tree view from lsusb under Linux, dunno what it is, though.

Its called USBView and its made by Microsoft, you can also see everything with HWInfo, USB AND PCIe.

No, “it” is not.

IT is named USBTreeView by Uwe Sieber https://www.uwe-sieber.de/usbtreeview_e.html

and is only kinda(?) based on M$’s lame USBView… ;-)

The level of hate some people carry for Microsoft and the unwillingness to give them an inch is hilarious.

The UsbTreeView app is literally a fork of USBView because Microsoft graciously released the source code for the app, which previously was only available as a binary in the Windows Driver Development Kit.

UsbTreeView only exists because of USBView and the fact that Microsoft recognized that the app’s source code had value to the Windows community.

can confirm audio tends to be where usb problems pop up. i have a usb microphone on my raspberry pi 4b, and whenever i run audacity it tries to initialize the sound driver in some sort of DMA mode, and the whole raspi immediately locks up hard. (side story, no point trying to debug it…you will not get a community-provided patch to this kernel bug because raspi i/o drivers all go through badly-designed closed source layers) obviously, it works on my laptop but i don’t want to use the laptop for recording.

audacity always tries to open the devices in dma mode to minimize latency so you can monitor your effects in real-time. i didn’t want that feature and a consistent quantifiable latency so the tracks can be aligned with eachother was my only goal, so i wrote my own multi-track recorder that uses the default i/o, and it works fine even on the pi.

i bring this up because i wouldn’t be surprised if your streaming software also tries to use a dma mode, when really a non-dma mode would probably suffice. kind of frustrating how things bend over backwards to minimize latency when quantifying it for sync is really all that’s necessary. wouldn’t matter except that the dma mode is still sketchy for whatever reason.

as a counterpoint, for non-audio uses, i am using a 20+ year old 12′ usb-A extension cable with a 20+ year old unpowered usb 1.1 hub and it started to flake out on me (constantly resetting my devices…which means the dang backlight on my keyboard kept turning on) so i sprayed contact cleaner in all of the jacks (with it still plugged in to my pc, naturally) and then did the insert/removal dance a couple times for each, and now it’s rock solid again. when usb ‘just works’, it really just works!

I worked at a software company that installed and supported automated carwash systems. It was quite surprising how often a bit of the old in-out was the solution to USB problems. I think you can even end up with capacitance building up and discharging with corrosion and such. I don’t remember what R&D said anymore, but the confirmed dirty USB ports cause the weirdest problems.

” i have a usb microphone on my raspberry pi 4b, and whenever i run audacity it tries to initialize the sound driver in some sort of DMA mode, and the whole raspi immediately locks up hard”

That’s why I liked USB 3.0, it provided DMA as an alternative to polling and bulk transfer.

The original USB 3.0 predated the USB naming chaos, also.

USB 3.0 was fine for external HDDs, for devices in need of more current.

I really liked USB 3.0 with the old USB A and USB B connectors.

Looking back it was first time that I liked USB, at all, I think.

Because I still miss the traditional PC connectors..

Serial, Parallel, Gameport/MIDI-Port, 8-Bit SCSI, PS/2 keyboards..

These connectors were so fun to tinker with!

The Gameport had an ADC that could be used to digitize analog data and it had four digital switches to read out.

You could directly read the port states in Visual Basic, for example.

Or let’s take serial ports.. DOS/Win/3.1/95 Games used to support null-modem gameplay.

Back in the 90s, you made your own 20m 3-wire cable on a weekend.

That was fun!

Heck, I even miss FireWire! 😃

It was so much better than USB, especially in audio applications, video editing and networking!

Professional audio equipment had featured FireWire ports, too. Much better than stuttering USB 1.x/2.x!

Parallel was kinda nice, though limited pre ECP. The gameport? Crap implementation, like seriously, a naked value -> time device using an RC timer. Yes, it could work nice given a processor dedicated to sampling. Not good in any way or form!

Nah kid, the Gameport was fine! 😄

There had been speed-compensated versions, too!

These ran fine on PCs past the 486 generation, even if old games/applications were used.

The nanslog nature of the Gampeport was fine for flight sims and racing games with a wheel!

By comparison, the Atari digital joystick was a joke here!

IBM itself intended the gameport to be a DIY port, also.

On the “IBM Game Control Adapter” there’s even a spare through-hole section on the card, for soldering! 😃

Next to the text “analog input card”.

So it was meant to be a hacker’s port from very beginning! Isn’t that awesome! Yay! 😃

Here’s a picture (fourth card top down):

https://www.minuszerodegrees.net/5150_5160/cards/5150_5160_cards.htm

“Clearly, IBM were catering for engineers who wanted to use the card for a purpose other than a game port.”

Here’s the manual:

https://www.minuszerodegrees.net/oa/OA%20-%20IBM%20Game%20Control%20Adapter.pdf

The X/Y axis channels could be used separately to directly interface a photo diode, an LDR or an NTC/PTC!

With an 4,77 MHz 8088 processor and an unmodified standard game port with the default caps,

you could cover almost a whole 8-Bit range (ca. 10 to ca. 200 values).

That was fine for a long-time oscilloscope or data logger.

For a faster processor (V20 or 286/386/486) the range got smaller, of course.

But that could be compensated by soldering some extra caps in parallel, to delay things.

Or by using a speed-compensated game card, of course! 😃

Okay kid, you might not be impressed by this – but the limitations and the simplicity were fun and challening!

Especially because there was no darn microcontroller in the way!

It was an archievement to develop something for gameport.

On a breadboard, with lots of wires. If necessary in an amateurish, hackish style.

The digital buttons could be used for a light barrier or a revolutions counter.

So you could measure how fast, say, a motor was running by counting the pulse rate.

Together with Quick Basic or Turbo Pascal you could write fun little programs asa hobby.

This way such an relaxation! 🙂

There were so many projects you could build that would interface with a parallel port or even an ISA bus with just 7400 series logic. The old ports were all fairly simple and easy to use. The standards were open and well documented.

Now you need an FPGA with some proprietary IP block for USB 3 or PCIe. You certainly won’t be able to photocopy that PCB layout from a magazine and do a toner transfer.

“The old ports were all fairly simple and easy to use. The standards were open and well documented.”

They were simple. The standards were not open and well-documented. Not even close. ISA DMA, ports, and interrupt sharing were all Wild Wild West, which is what led to total and complete incompatibility between things (you obviously can’t share an interrupt if one wants level and one wants edge).

Modern standards are exceptionally well-documented, just oftentimes behind some working group’s paywall.

“Now you need an FPGA with some proprietary IP block for USB 3 or PCIe.”

Yeah, because you can’t run jellybean logic at 5 GHz? You can bitbang I2C, SPI, USB 1.1, or even 10 Mbit Ethernet. An RP2040 can interface to LPC easy. How was it easier when you had to interface stuff with logic that if you screwed up, you could fry something that in today’s dollars would be $5-10K? Whereas nowadays you can do it in software?

Turbo XT clones were pretty affordable by late 80s, I think.

And before this, there had been no-name 1:1 IBM PC clone motherboards from Hongkong/Taiwan in 1985 or so.

They lacked IBM BIOS and ROM BIOS, so an anonymous XT BIOS was supplied, if at all.

Serial/Parallel/Game port were sometimes on-board, but mainly being located on expansion cards.

Either individual ones or multi-i/o cards.

Damaging the parallel port was possible, but also just a matter or replacing/fixing a card.

What ISA bus (formerly AT-Bus) sets apart is that it really is (was) an “Industry Standard Architecture”.

Prototyping was easily done with this bus.

Also, what young people properly don’t get is the following:

Tinkering with such “ancient” technology is all about working with electronics, with a soldering station, with discreet parts that have a clear function.

Even ICs, which are explained in great detail in their datasheets.

You’re litteraly dealing with physics, so to say.

By contrast, working with modern “I2C, SPI, USB 1.1, or even 10 Mbit Ethernet” it’s all about writing software and stacking modules together.

How things work from ground up nolonger matters. The black box does care about.

It’s like asking an assembler programmer to switch to C, Rust or Python or something.

He/she might get the switch done, but does he/she have same fun as with assembly before?

“Not even close. ISA DMA, ports, and interrupt sharing were all Wild Wild West, which is what led to total and complete incompatibility between things (you obviously can’t share an interrupt if one wants level and one wants edge).”

Bravo, you described the two worst shortcomings of ISA! :D

On other hand, IRQs and DMAs were basically all being assigned already in an unexpanded PC.

Especially on an PC/XT with the 8-Bit slot or 8-Bit cards (popular in prototyping).

So if there are no resources left to begin with, then the problem of sharing them goes away on its own, doesn’t it? ;)

“They were simple. The standards were not open and well-documented. Not even close. ISA DMA, ports, and interrupt sharing were all Wild Wild West, which is what led to total and complete incompatibility between things (you obviously can’t share an interrupt if one wants level and one wants edge).”

I think that many ISA prototype cards had used i/o ports or polling or memory-mapped i/o.

ISA DMA was a thing in the days of the PC/XT class computers, when the DMA controller was still ahead in terms of performance.

But as the years went on, it was easier and quicker to use CPU-controlled i/o instead.

What many not see is the relationship to CP/M, *nix and Linux maybe:

The DOS platform wasn’t just something owned by intel/ibm/microsoft even if they served as role models quite often.

It rather was an open platform with many component makers and DOS compatible OSes.

Not just counting the dozen of OEM versions of MS-DOS, but also independent OSes that could run DOS software.

Just like in in CP/M days, when various no-name OSes could run CP/M applications.

There also were multitasking OSes among them, which had virtual terminals as found on Linux.

IT wasn’t as monolithic as it is now. Also, binary compatible did still exist back then.

“Turbo XT clones were pretty affordable by late 80s, I think.”

Weird definition of affordable. Still O($1K) for a minimal setup, which is almost $3K in today’s dollars. You can poke around and break stuff for under $50 nowadays. This is a much easier time to learn.

“I think that many ISA prototype cards had used i/o ports or polling or memory-mapped i/o.”

Yes! And programmed I/O forces the CPU to run at the speed of the bus! Which means there’s literally no way to speed it up. With a bus (more than a point-to-point connection) you’re going to be limited to way below 50 MHz. The only way they were able to get a parallel bus operating beyond ISA was by stringent clock and driver requirements (PCI) and that only bought them up to ~66 MHz or so. I’ve pushed PCI a bit faster for shorter runs, but even 66M falls apart easily.

Using programmed I/O on a device to learn about electronics means you should be using a slow device. The ports can’t be fast. It’s just physics. You want a fast computer, you can’t have slow programmed I/O ports on it.

The thing is that computers with simple programmed I/O busses haven’t gone away! They’re just microcontrollers now! A Raspberry Pi Pico could easily do an ISA bus.

It’s just a consequence of needing to improve the transfer rate.

A whole article and days (weeks?) of troubleshooting USB devices on a Windooze machine and no mention of https://www.uwe-sieber.de/usbtreeview_e.html ?

There‘s the equivalent of the lsusb tree view under Linux. Yeah, talking about how devices are physically hooked up in USB is pointless, you need the actual way they’re hooked up as viewed by the protocol.

Each USB camera needs to be plugged in to the its USB host controller. Its best to build a computer using a motherboard with dedicated PCIE lanes for each host controller. Don’t run any real data interfaces through a hub. Cameras and audio interface USB drivers/classes just aren’t made for that.

In my experience hubs are fine as long as they’re rated for the same or higher speed as any downstream device AND are adequately powered. My current setup is 4 hubs deep and rock solid.

Laptop -> Thunderbolt Dock -> USB Switcher (Keyboard, Mouse, Monitor Hub) -> Monitor Hub (4k Webcam, USB Hub) -> USB Hub (Wireless Headset, SD Card Reader, +2x ports)

If you’re talking about a USB2 or lower device, the “rated for same or higher speed” is pointless. USB2 devices are just “embedded within” USB3. They don’t translate anything or aggregate anything. Just think of it as a USB2 hub glued on top of your USB3 hub.

I’m trying to understand how you misconstrued what I said. I’m saying this is bad:

PC > USB1HUB > USB2HUB > USB3HUB > Device

It’s only the USB1 -> USB2 hub that matters. The USB2 -> USB3 -> USB2 is exactly the same as USB2->USB2->USB2. The high-speed path and the low speed path are totally separate. It’s not the same as USB1/2 where USB2->USB1 with MTTs is better than USB1->USB1.

Many computers have only ONE USB host controller, and use internal hubs to fan that out to however many USB jacks are on the computer.

This is close to what I was thinking. Hardware quality is the likely culprit imho. You mentioned laptop, i7, and 16gb ram, but is the laptop a budget machine or a piece of quality hardware.

MacBooks and similarly priced Windows laptops provide simply higher quality. For example, running external ports at high speed simultaneously tends to work on higher quality machines. You try the same on a $600 laptop and it just won’t be as good.

I had that issue when I needed to record two webcam videos during an experiment. Only one camera would work when both were plugged into the machine. I tried using a docking station (older Dell laptop so not Type C) and found that all of those ports were also still on the same host controller. The “docking station” was really just a port expander with a built-in USB hub. I ended up buying a USB 3.0 ExpressCard that offered it’s own host controller. Everything worked great after that. I setup ffmpeg to record the video locally while also streaming it over the network to another machine for remote monitoring. We wanted to add another camera to the system but I was out ways to add more host controllers so we just made do with two.

After the project, I realized I should have just bought three IP cameras and a 4 port switch and saved myself the time.

Good morning Lewin,

As Bill stated, try a wired ethernet port and disable the wireless ethernet.

From your symptoms, the issue ONLY arises when the wireless port is being heavily used by streaming.

I believe you MAY have an interrupt issue where the wireless ethernet is using the same interrupt as one (or more) of your serial ports.

Hope this helps identify and perhaps correct your issues.

Regards,

Rick

It doesn’t need to be interrupts – I have seen some USB devices creating radio interferences with 2.4 GHz Wifi. I have also seen other people report similar issues.

Just use wired ethernet for everything that must be low-latency and reliable, like streaming.

Exactly this. The article mentions a USB dongle for wireless keyboard and mouse. These cheap things generate a TON of 2.4 GHz noise.

It’s a common enough issue that when I contacted CalDigit support about having issues with my Thunderbolt dock, the first question they asked was “do you have a wireless keyboard and / or mouse connected?” I moved the wireless dongle to an isolated hub on my monitor and everything has been working flawlessly since.

There’s also optical ethernet for the really noise sensitive environments. As an alternative, I mean.

The usual RJ45 ethernet cabling causes/receives quite some RF noise, too, despite being twisted-pair.

Radio amateurs often tell their stories about this.

Using ferrites helps a bit, but sometimes decoupling CAT cables through transformers or opto-couplers is required.

Twisted-pair Ethernet is already transformer-coupled at both ends, by design.

If you’re getting more RF interference out of the CAT 5 cable than directly from the devices it serves, then something is wrong.

You use optocoupling (or fiber) when the 1500 volt isolation provided by twisted-pair interfaces isn’t enough.

“Twisted-pair Ethernet is already transformer-coupled at both ends, by design.”

But not in practice, I suppose. Not always.

There are many USB MIDI cables which are supposed to be opto-coupled, but are not.

Instead, a simple resistor is used. Not even pull-up or pull-down transistors.

“You use optocoupling (or fiber) when the 1500 volt isolation provided by twisted-pair interfaces isn’t enough.”

Somehow I get the feeling that’s not the only reason why wise people go optical.

You might be able to find capacitor-coupled Ethernet interfaces in cost- or space-reduced short-haul applications, but they are rare. Generally, if you find a RJ-45 jack that doesn’t have a transformer behind it, it’s not for Ethernet.

Wisdom is not simply “to go optical”. Wisdom is knowing when to choose one over the other.

“Radio amateurs often tell their stories about this.”

Yeah, there was a ‘ferrites help!!’ article on here before, but the actual emissions from Ethernet via SF/UTP cable is pretty negligible, at least 20 dB under Class B limits (Wurth Electronik’s got an app note on this, ANP116).

And clamping ferrites on it doesn’t actually do anything about the actual emissions from the protocol, because it can’t: the protocol’s common-mode free at the frequencies of interest.

Generally throwing ferrites on stuff is just a band-aid: a shield’s probably not connected somewhere, or you’re not actually seeing emissions from the cable, just reflections off of it. A long cable’ll be a decent reflector at low frequencies.

What edge case? The article doesn’t even narrow down a specific “case”.

It happens only when streaming yet the scope never went away from “fiddling” with USB stuff.

I recently switched work computers and the Windows audio service on my new one crashes whenever the speaker is enabled on a Logitech webcam. If I go into device manager and disable the webcam’s speaker everything is hunky dory again. wouldn’t hurt to tythe same in you’re situation, at least under what seems a fairly safe assumption that you aren’t using its speaker.

Put a KVM in the middle and get all the USB devices to work right on 2 computers. Just for kicks make those 2 computers be virtual machines with passed through PCIE USB controllers.

The internal WiFi on PCI Express Mini Card may be using the USB channels on the PCI Express Mini Card connection instead of PCI-Express channels.

Agreed. There’s not even certainty that this is a USB issue.

No logs? No USB protocol sniffing?

We learned nothing except extended details of his gripe.

I agree, this is not a hack. This is an IT service request ticket: “it’s broken and I don’t know why”.

USB3 operates at a base frequency of 2.5GHz but uses spread spectrum to lower narrow-band interference. That means it may drop into the 2.4GHz WiFi bands for transceivers next to the USB cables and ports. Its first harmonic may affect the 5GHz WiFi bands as well.

Splurge on an Ethernet cable, Lewis.

Even without the spread spectrum technology, just the data modulation will generate a wideband noise blob from DC to 5GHz.

“You’d think an i7 with 16 GB of RAM would be well equipped to handle some audio software, 40 plugins, and a couple of webcams.”

and on the fly greenscreening and streaming out all at the same time? Dunno what i7 are you using, there’s a huge difference tween an i7-860s and a i7-13700K, ya know they have been making them for like 16 or so years now, so i7 doesnt mean shit

Yep, I have a laptop with a gen 2 or 3 i7 in it – and the thing only has two physical cores!

Suffice it to say, that i7 is less capable than a much newer i5 or perhaps even an i3.

I had a similar problem with audio equipment operating on USB back in the Core 2 / i7-9xx workstation days – It was the onboard audio brand (Realtek) interfering with things.

Disabling it or buying a motherboard with a different brand chipset did the trick for this customer. Having it onboard and even inactive (not hardware disabled) caused stuttering.

What a rabbit hole audio is in virtual space. There’s Voicemeeter banana (jack for windows) and other ways into something I know little of outside of audacity. Linux was hell then real good but the latest versions of Ubuntu are silent or making noise instead of sound. Too many ways to do audio now, something like 5 or 6.

Sometimes you need the schematic diagram, or at the very least the block diagram of the system to see where the bottlenecks are.

The mention of interrupts is a good spot to look. Also see what mode your processor is in. It’s possible it is taking ‘micro-naps’ in a low power mode and this is preventing it from catching the interrupts.

Possibly getting a USB-C.

Also be aware that every Bluetooth implementation is USB based, it might be a good idea to completely disable the Bluetooth and the WiFi too and use something like a GL.inet router if necessary.

Maybe see if there is a USB 3 capture device that can pull from an HDMI camera? (A lot of the cheap ones have blue ports but are still USB 2.0.)

Maybe even use a network camera to get the dice roll screen? What are the odds there is a sound device like a Mic on the webcams? That would make 4 sound devices, all of them possibly USB connected, see if the ones not in use can be disabled.

I cannot tell you how useless the documentation on modern laptops and PCs are when it comes to hardware specifications. I have an HP OMEN desktop motherboard here that the HP Website claims has no video output. Yet I’m getting DisplayPort Alt mode from the rear USB-C. To Be Fair they aren’t even hosting the specs anymore, I had to use Archive .org’s WayBack Machine. (And people wonder why Lenovo has goodwill, it’s clear consistent and free documentation, for the most part).

Should have used linuuuuuxxxxx

Lol

But seriously don’t rule out the laptop being the issue. Honestly I would try running the entire setup from a single powered hub just to cut your failure points down to one and decomplicate what your onboard USB has to handle (something that only makes sense with IT issues…)

And don’t rule out the wifi card either being on an internal USB connection, or it ramping it’s power every once in awhile to fight with other Wi-Fi devices for a clear link, and then interfering with your USB chipset.

Dumber things have happened (I’m looking at you Galaxy S4 with your dumb 3G modem interfering with the back button in high power low signal situations).

And as with all IT problems. Good luck, and please document the eventual fix.

I can’t believe you even attempted it without a powered hub. You have to have to have enough amps to power all your devices, INCLUDING any spikes you might have. I would start with a USB Voltage and amp multimeter. Check for a spike when you turn it on and check for any changes when you start streaming. The streaming software might be increasing the amp draw somehow.

And here we see some of the reason (most) “Workstation” laptops cost $1000 more for similar looking specs…

Fewer corners cut = less hair pulled out attempting to force windows applications with complicated IO play nice with others.

Instead of yet another “better” hub, Go spend $200 on last year’s desktop Optiplex or Thinkststation from a government auction, and spend your time making more music instead of learning in-depth how this rabbit hole can send even the most sane man postal :)

Article does things a certain way YOU’RE DOING IT WRONG

Article asks for the right way to do it HOW DARE YOU ASK FOR HELP

Many USB audio interfaces and some USB webcams use isochronous data transfer mode. In that, the device reserves an amount of bandwidth in advance. Ideally it’s the amount it is going to use, but nothing stops the device from reserving more than it actually needs. It can then lead to best-effort transfer modes such as bulk endpoints being limited.

Thunderbolt/USB4 docks (if supported by the laptop) typically offer PCIe USB controllers for their ports rather than an internal USB hub. You may find they work closer to a native port than your hub nightmare experience. That has been the best solution I’ve found so far.

It’s also possible some of this is due to marginal signal integrity and USB signal regenerators may help. Unfortunately they are difficult to find standalone and mostly exist inside long extension cables. This is definitely the case for cables that advertise they use fibre optics inside (although you may want a powered hub on the far end to ensure enough power is available). I’ve never actually found a satisfactory solution going this route.

I hate troubleshooting audio issues, there’s always something different wrong with it, there are millions of settings and workarounds to try and nothing is ever easily discoverable. And you have already gone five levels deep with this one.

I understood this as a call for brainstorming, so here goes nothing :)

Is there dropout detection of some sort in Ableton? I think Cakewalk (or was it Cubase?) would light a red bulb in the UI when there’s something wrong with the audio stream. I believe it also had some kind of logging where it showed a message saying what happened… I don’t know if this would provide any helpful information but it might be worth looking into.

Now that I think of it, maybe even ASIO4All has it? You could try using it as a temporary replacement. I’ve had no issues uninstalling it and reverting to a different driver so it shouldn’t hurt – other than wasting time which is a given. Since it supports multiple devices, it might even let you run the headset through it (don’t know if that would be of any help with the setup but might provide some clues).

Also, I was under the impression that Windows doesn’t like/allow using multiple audio devices with my DAW, apparently there’s some kernel deficiency that MacOS has sorted out but not Windows… I always plug my instruments and headphones into the same USB audio interface, it doesn’t even seem to work any other way – except with ASIO4All which allows connecting multiple devices, although even that doesn’t always go smoothly.

Are you on Windows 11 24H2 with a Intel AX411/AX211/AX210/AX201/AX200/9560/9462/9260/7265/3165 ? If so, I would be curious whether the version 22 driver changes anything. Or 23H2 or another OS, but the former is easier. Just a wild goose chase, of course, but sometimes you catch the goose.

Update: This actually fixed an issue with a dell laptop at work; I have had no further complaints about usb mouse/keyboard issues since changing the wifi driver out. Perhaps it’s not limited to the above-listed models – I could easily believe windows 24h2 changed something that both families of wifi card rely on.

Have you tried turning it off and on again?

This article isn’t finished yet.

There needs to be around two or three more paragraphs where you fixed the issue.

Granted!

If you have an old android phone laying around, you can use it with DroidCam to stream camera video over your wifi. Supports video only, audio only, or both. So you can plug in a lapel mic (or even a USB mic with an OTG adapter) to turn it into a wifi streaming wireless mic.