When the microcomputer first landed in homes some forty years ago, it came with a simple freedom—you could run whatever software you could get your hands on. Floppy disk from a friend? Pop it in. Shareware demo downloaded from a BBS? Go ahead! Dodgy code you wrote yourself at 2 AM? Absolutely. The computer you bought was yours. It would run whatever you told it to run, and ask no questions.

Today, that freedom is dying. What’s worse, is it’s happening so gradually that most people haven’t noticed we’re already halfway into the coffin.

News? Pegged.

The latest broadside fired in the war against platform freedom has been fired. Google recently announced new upcoming restrictions on APK installations. Starting in 2026, Google will tightening the screws on sideloading, making it increasingly difficult to install applications that haven’t been blessed by the Play Store’s approval process. It’s being sold as a security measure, but it will make it far more difficult for users to run apps outside the official ecosystem. There is a security argument to be made, of course, because suspect code can cause all kinds of havoc on a device loaded with a user’s personal data. At the same time, security concerns have a funny way of aligning perfectly with ulterior corporate motives.

It’s a change in tack for Google, which has always had the more permissive approach to its smartphone platform. Contrast it to Apple, which has sold the iPhone as a fully locked-down device since day one. The former company said that if you own your phone, you could do what you want with it. Now, it seems Google is changing its mind ever so slightly about that. There will still be workarounds, like signing up as an Android developer and giving all your personal ID to Google, but it’s a loss to freedom whichever way you look at it.

Beginnings

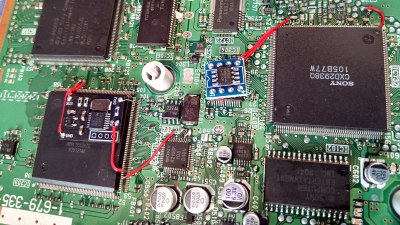

The walled garden concept didn’t start with smartphones. Indeed, video game consoles were a bit of a trailblazer in this space, with manufacturers taking this approach decades ago. The moment gaming became genuinely profitable, console manufacturers realized they could control their entire ecosystem. Proprietary formats, region systems, and lockout chips were all valid ways to ensure companies could levy hefty licensing fees from developers. They locked down their hardware tighter than a bank vault, and they did it for one simple reason—money. As long as the manufacturer could ensure the console wouldn’t run unapproved games, developers would have to give them a kickback for every unit sold.

By and large, the market accepted this. Consoles were single-purpose entertainment machines. Nobody expected to run their own software on a Nintendo, after all. The deal was simple—you bought a console from whichever company, and it would only play whatever they said was okay. The vast majority of consumers didn’t care about the specifics. As long as the console in question had a decent library, few would complain.

There was always an underground—adapters to work around region locks, and bootleg games that relied on various hacks—with varying popularity over the years. Often, it was high prices that drove this innovation—think of the many PlayStation mod chips sold to play games off burnt CDs to avoid paying retail.

At the time, this approach largely stayed within the console gaming world. It didn’t spread to actual computers because computers were tools. You didn’t buy a PC to consume content someone else curated for you. You bought it to do whatever you wanted—write a novel, make a spreadsheet, play games, create music, or waste time on weird hobby projects. The openness wasn’t a bug, or even something anybody really thought about. It was just how computers were. It wasn’t just a PC thing, either—every computer on the market let you run what you wanted! It wasn’t just desktops and laptops, either; the nascent tablets and PDAs of the 1990s operated in just the same way.

Then came the iPhone, and with it, the App Store. Apple took the locked-down model and applied it to a computer you carry in your pocket. The promise was that you’d only get apps that were approved by Apple, with the implicit guarantee of a certain level of quality and functionality.

It was a bold move, and one that raised eyebrows among developers and technology commentators. But it worked. Consumers loved having access to a library of clean and functional apps, built right into the device. Meanwhile, they didn’t really care that they couldn’t run whatever kooky app some random on the Internet had dreamed up.

Apple sold the walled garden as a feature. It wasn’t ashamed or hiding the fact—it was proud of it. It promised apps with no viruses and no risks; a place where everything was curated and safe. The iPhone’s locked-down nature wasn’t a restriction; it was a selling point.

But it also meant Apple controlled everything. Every app paid Apple’s tax, and every update needed Apple’s permission. You couldn’t run software Apple didn’t approve, full stop. You might have paid for the device in your pocket, but you had no right to run what you wanted on it. Someone in Cupertino had the final say over that, not you.

When Android arrived on the scene, it offered the complete opposite concept to Apple’s control. It was open source, and based on Linux. You could load your own apps, install your own ROMs and even get root access to your device if you wanted. For a certain kind of user, that was appealing. Android would still offer an application catalogue of its own, curated by Google, but there was nothing stopping you just downloading other apps off the web, or running your own code.

Sadly, over the years, Android has been steadily walking back that openness. The justifications are always reasonable on their face. Security updates need to be mandatory because users are terrible at remembering to update. Sideloading apps need to come with warnings because users will absolutely install malware if you let them just click a button. Root access is too dangerous because it puts the security of the whole system and other apps at risk. But inch by inch, it gets harder to run what you want on the device you paid for.

Windows Watches and Waits

The walled garden has since become a contagion, with platforms outside the smartphone space considering the tantalizing possibilities of locking down. Microsoft has been testing the waters with the Microsoft Store for years now, with mixed results. Windows 10 tried to push it, and Windows 11 is trying harder. The store apps are supposedly more secure, sandboxed, easier to manage, and straightforward to install with the click of a button.

Microsoft hasn’t pulled the trigger on fully locking down Windows. It’s flirted with the idea, but has seen little success. Windows RT and Windows 10 S were both locked to only run software signed by Microsoft—each found few takers. Desktop Windows remains stubbornly open, capable of running whatever executable you throw at it, even if it throws up a few more dialog boxes and question marks with every installer you run these days.

How long can this last? One hopes a great while yet. A great deal of users still expect a computer—a proper one, like a laptop or desktop—to run whatever mad thing they tell it to. However, there is an increasing userbase whose first experience of computing was in these locked-down tablet and smartphone environments. They aren’t so demanding about little things like proper filesystem access or the ability to run unsigned code. They might not blink if that goes away.

For now, desktop computing has the benefit of decades of tradition built in to it. Professional software, development tools, and specialized applications all depend on the ability to install whatever you need. Locking that down would break too many workflows for too many important customers. Masses of scientific users would flee to Linux the moment their obscure datalogger software couldn’t afford an official license to run on Windows;. Industrial users would baulk at having to rely on a clumsy Microsoft application store when bringing up new production lines.

Apple had the benefit that it was launching a new platform with the iPhone; one for which there were minimal expectations. In comparison, Microsoft would be climbing an almighty mountain to make the same move on the PC, where the culture is already so established. Apple could theoretically make moves in that direction with OS X and people would be perhaps less surprised, but it would still be company making a major shift when it comes to customer expectations of the product.

Here’s what bothers me most: we’re losing the idea that you can just try things with computers. That you can experiment. That you can learn by doing. That you can take a risk on some weird little program someone made in their spare time. All that goes away with the walled garden. Your neighbour can’t just whip up some fun gadget and share it with you without signing up for an SDK and paying developer fees. Your obscure game community can’t just write mods and share content because everything’s locked down. So much creativity gets squashed before it even hits the drawing board because it’s just not feasible to do it.

It’s hard to know how to fight this battle. So much ground has been lost already, and big companies are reluctant to listen to the esoteric wishers of the hackers and makers that actually care about the freedom to squirt whatever through their own CPUs. Ultimately, though, you can still vote with your wallet. Don’t let Personal Computing become Consumer Computing, where you’re only allowed to run code that paid the corporate toll. Make sure the computers you’re paying for are doing what you want, not just what the executives approved of for their own gain. It’s your computer, it should run what you want it to!

Answer: Microsoft

Apple is much worse than Microsoft in regards to software lock down.

The “Open Letter to Hobbyists” was the first step on a long path to here.

If you lived through those times or even bothered to read the blurb above, you would know that is not the answer. You have poor reading comprehension and are mad at yourself about something. Probably best to take the day off, get a couple of tacos and several brews, and not ever ever learn anything :)

Freedom kind of an illusion isn’t it especially in light of the HaD articles about E-waste and we can’t do with phones like we do with PCs lament?

If you buy into a locked-down system by pay for a device, it’s not your computer. It’s only your device. The computer is a whole, comprised of both software and hardware. If you don’t control both, it’s not your computer.

P.S. The comment interface really needs a preview.

“lol”

During DOS times end lusers were just as clueless about computers as they are today. The difference is a virus back then would show some offensive phrase, make letters fall to the bottom of the screen or wipe the 8-megabyte hard drive. With always-connected PCs, laptops and smartphones of today, unrestricted spread of malware could cause damage far greater than a 500-strong swarm of Geran drones.

We can:

a) prevent normies from running unapproved code, turning computer into yet another appliance comparable to washing machine or game console.

b) disconnect everyone and everything from the Internet

c) bring everyone’s knowledge of programming, operating systems and IT security to the level of kernel hacker running his own LFS/yocto distro.

Realistically speaking only option a) is feasible.

Oh no, someone listed three options for an unrelated problem and somehow the one they want is the only feasible one. Gosh, we should call that something… hay man? grass man?

Should be pretty clear that human-in-the-loop code authorization (e.g. which looks shockingly like “dialogue boxes”) would be EITHER: enough to stop fantasy out of control malware,. OR: that lack of authorization wouldn’t stop the malware, which was conveniently ignored above – perfectly possible to be non-free and have malware. Doesn’t mean you have to line up your neck to be stomped on.

What the next reasoning? We’ve had “improving cybersecurity”, so the usual suspects coming up will be….”protecting the children”, before that “defending from terrorists”, before that “protecting the recording industry”, “protecting against communism”, before that “protecting against fascists”.

I was in my 20’s when I found out (from a child) that the reason the #6 was terrified of the #7 was entirely bc the #7 are the #9!!!

So here we are still again.

And these for profit company ‘curated’ ‘approved’ experiences are actually safer?!?!?!?!

I’d love to see the complete known world-wide set of data combined for this sort of thing, but the non tech savy if I can’t configure it I don’t want it person’s locked down IOT device is almost certainly part of a botnet, accessible remotely without their authentication, a backdoor into their local network etc. At least if their equally locked down usually garbage ISP router hasn’t actively prevented it (and as they don’t care, as you have to pay them anyway…).

The Apple and Google Play store has been full of dubious applications of many types, some of which last for many years after the first report of fishy behaviour – as again these companies really don’t have any reason to care how screwed over you get as long as you keep paying them their cut! And you the user have ever fewer ways of knowing how the bad stuff happened to you…

The only thing that actually protects the normies is that the tech savvy have enough access to similar hardware and software to find and fix the flaws that bother them individually and can submit them to collective. Which leads to the whole collective having access to a fairly secure and functional system as a rule.

Very much the FOSS model of the real Linux distro. Which is a good option as you have the chain of trust in the package management system, everything is signed so the normies have that easy playstore like way to install and keep updated ‘secure’ programs and the experts get to inspect each others work and will eventually (usually rather fast) find the bad actors and correct it. Along with real access to all the tools to debug should anything actually go wrong. Still doesn’t in any way restrict a normie or the technically capable from installing anything bad from outside – but its rather easier to find the problem…

Or:

d) Make everything restricted by default and allow to disable restrictions in advanced options but with strong “are you sure” warning pop up window. Regular users will not even know to switch it and advanced users will get needed access.

“. With always-connected PCs, laptops and smartphones of today, unrestricted spread of malware could cause damage far greater than a 500-strong swarm of Geran drones.”

For over a decade nearly every Android device received 2 updates per year for 2-3 years and this was not considered a problem by both Google and device manufacturers. So how big was the issue with side loading apps?

Which sounds great in theory, but way too many normies are clueless enough to click through those strong “are you sure” warnings when instructed by bad actors over the phone.

I like the Chromebook approach more. If you want to go into developer mode to do silly things you need to wipe the device first. Then you get a big fat warning every time you power up and if you look at it wrong it goes back to locked down mode. And if you want to flash custom bootloader, sure, go ahead, but you need to open the case and remove a write-protect screw first.

” too many normies are clueless enough to click through those strong “are you sure” warnings when instructed by bad actors over the phone.”

My mother in law trusted some bad actor and tried to “invest” money but her bank noticed strange operations and locked her account. It took her 2 days to get this access back – she had to go to the bank and on the place got informed that this was suspicious operation. My wife explained her it’s a scam at home. So my mother in law contacted this bad actor and lost those money anyway. This scam involved no need to install any app. Imagine level of restrictions she should get. Now imagine that to save her alike we all should be restricted as much.

Meanwhile companies began to train their employees in cyber security and finally people stopped clicking every link, opening every file and start to read carefully emails.

And while I hate it, I understand why the companies would want to do this. The lower chance of someone saying that the popup on their phone did not warn them clearly enough they could lose money, the lower chance of a lawsuit and/or bad press. And all those pesky power users complaining? That’s 0.1% of the user base, it won’t even make a dent in their sales figures.

Complexity and a huge variety of software on different OSs leads to all kinds of vulnerabilities:

Pwn2Own Day 2: Hackers exploit 56 zero-days for $790,000

October 22, 2025

Security researchers collected $792,750 in cash after exploiting 56 unique zero-day vulnerabilities during the second day of the Pwn2Own Ireland 2025 hacking competition.

No, realistically the only option to ensure security is to prevent EVERYONE from running unapproved code. And in that case we must remember the quote from the great Benjamin Franklin, “Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety”.

The majority of developers do not personally build their own toolchain from assembly, and injection of code into compilers is a very real possibility as Ken Thompson had described in “Reflections on Trusting Trust” – meaning that everything is potentially insecure. A major open-source compiler may have had its source code audited by the numerous authors, and the source code is clean of malware, but somewhere in the past someone may have injected something into the code to build a compiler that built the next compiler. And that compiler may have deeply-embedded flaws that will compile future compilers, and maybe other software, with similar flaws.

If you are one of the few who has personally built your own compiler from assembly, and has checked other compilers by then building them from their source code as well as using their prior compiled compilers, congratulations! For the rest of us, even people like me who put new firmware on IOT light bulbs before putting them on my network, security is never perfectly guaranteed. And we need to accept that risk, or we need to give up an essential freedom in our modern technical society, and that is not acceptable.

Now we have, normies, power users, companies, and governments having to blindly trust half a dozen companies to care about solving their problems, fixing any issues, deign to be compatible with lesser software and not kill it with a worse version, and either buy everything again after a couple of years, or rent at ever more extortionate monopolistic prices. All while making creative hobbyist hacking a lot less interesting for everyone that could innovate.

After reading this post a few times before hitting the submit button, I would like to offer the following apology in advance, to anyone who might be even slightly offended by my tone. My missive was not targeted specifically at the poster the I have chosen to respond to. It is intended for the education of ALL computer users who feel they are getting ripped off by software vendors. When you purchase a CD you do no own the music on that disk. You have purchased a license to use it under a fairly narrow set of conditions. The intellectual (creative) property on that CD was the product of considerable talent, effort, and time. Likewise, useful software takes considerable talent, effort, and time to produce. I think it is important that individuals who argue about the cost of software be conscious of that fact.

-dg

There is absolutely NOTHING in the world stopping you, or anyone else, from writing their own desktop applications, except skill, imagination, and patience. I don’t know what you do for a living, but I am a professional software developer, one who has made a living my entire adult life by writing code, leading development teams, and designing software products. I also spent over a decade as an industry professional who also wore the University Computer Science Lecturer’s hat. I taught Masters and Ph.D. students how to design, write, and support large-scale applications. The single most interesting thing I took away from that experience is that no matter how much code a student had written in the past, or how much they BELIEVED they understood the PC software market, not a single one of them had the slightest clue of what it actually costs to design, write, and support a commercial software application.

Anybody can hack together some Rust or JavaScript, throw it over the transom, and say, “I wrote a word processor, it’s open source, and absolutely free to use.” That argument is absurd on its face. Absolutely nothing in this world is free! What is your time worth per hour? How much frustration are you willing to tolerate because your spreadsheet crashes at random intervals during the day, or even worse gives you incorrect results that you dutifully use to file your federal income tax return? An MS Office license costs $70/year for the single-user version. For less than a single day’s labor at the federal minimum wage of $7.25/hour, you can “rent“ a piece of software that will pay for its cost at least tenfold, if not one hundredfold or more over its year of licensed personal use, and that is without even discussing the business necessity/value/reliance on such a tool.

It is very easy to stand on the sidewalk and throw rocks at software authors (and their sometimes greedy employers) you accuse of ripping you off with their “extortionate monopolistic prices.” I don’t work for free, and I have a strong sense that neither do you. If someone believes that $70/year is an excessive price to pay for a tool that even their retired mother-in-law probably uses at least a few dozen times per year, I’m not so certain they understand the time/value proposition very well.

Software development is one of the last technical fields where someone can still literally develop a product at their dining room table and be rewarded handsomely for their efforts. Perhaps, investing a little bit of that “creative hobbyist hacking” ethos in building your own tools would give you a different perspective on how expensive software development truly is.

My own “creative hobbyist hacking” revolves around cinema. If you think software tools are expensive, take a few minutes and look up the price of an Arri Mini LF, or a Cooke S3 lens, or Sony A7RV camera. A casual investigation of the three products I just mentioned would convince you they are obviously professional products, priced for professional users. I would argue that Adobe Photoshop, ProTools, and Ableton Live are also professional tools, even though MILLIONS of people use them daily for personal tasks.

“My time is not free” and “there is nothing stopping you from making your own” are not comfortable bedfellows.

what about one’s own personal, fully crewed semiconductor foundry?

The most successful scams around here for the last few years involve bamboozling the elderly over the phone into either handing over all their money to save their descendants from something (like lack of a backroom surgery after a car crash, despite an universal healthcare insurance system that for all its faults handles actual car crashes acceptably, or bankruptcy) or handing over all their money to save their money from scammers (usually using the method above). Zero unapproved code running on silicon (though neural networks are disputable). So your option a. clearly doesn’t realistically work.

We can:

destroy all communication systems, or

do eugenics, or

instantly establish a socialist paradise where scammers somehow won’t feel like continuing to scam people is a lucrative business, or

extend your idea of a central entity approving everything to phone calls and messaging

That is, assuming the actual sane option of accepting an occasional exploit success is off the table for some reason.

Also, 500 flying bombs doing less damage than a regular person’s phone/computer hack is some disgusting arithmetic. The former is counted in multiple lives, the latter rarely comes to one.

Anyone want to bet that Ford isn’t the HaD audience, but rather some Program Manager whose job it is to sell device lockdown methods?

The conspiracy theorist in me says this was always the plan. When “big data” realized that they couldn’t control the bits on the internet they needed to wrest control back. Hence apps. It was entirely possible to just keep HTML on the phones but a very deliberate decision was made not to do that.

So now every little thing I want to do requires an app. Park my car at a meter in the city? There’s an app for that. Convenient coincidence that that app can track my location realtime without my knowledge. Something that HTML probably could never do.

And now it’s just a matter of slowly locking down the app infrastructure.

I once predicted “approved bits only” on the internet, but that would require completely replacing the packet protocol so is practically impossible worldwide. So I rescind that prediction in the light of this new approach. Different means, same end.

At least until some form of Secure Boot is required to connect to an ISP.

Natch, I use the desktop mode in my mobile browser pretty much exclusively.

No Insta, and no FB/Messenger apps. I just load the webpage.

All browsers can now gather your location data you know, and an shitload of other data too, more than you can think of.

HTML.. come on now.

In fact it’s that every damn thing has to be connected to the internet that is the actual issue isn’t it? HTML.. pfft

The whole reason for ‘non approved’ apps is to use files and peripherals and network the way YOU want it.

Why not sandbox freaking google ads so they run in a virtual environment without visible output :)

And sandbox MS spycrap and have an AI make up data for them so they can chew on that instead.

While of course they roll out their super-approved windows updates that constantly bricks whole droves of computers by accident.. safely and approved, with no malware, your very own safe-brick™

I just block the entire google domain, the internet still works for me.

That’s because you are not blocking Google’s ASN. Your block is incomplete.

That ast one was a reply to [c]‘s comment.

Thanks approved and safe comment system.

SaaS crept in, on the backs of venture capital. So you can continue to rent what you used to own, while having a steady stream of advertising targeted at you.

Windows 10 needs cracked to remove the “security” and telemetrics that are baked in. Open source security updates would free up billions for industry and home users alike. Linux is not an option for most.

I understand that Linux isn’t an option for everyone, as some people do heavily rely on Windows-only software. However, I do believe that a very large chunk of Windows users would be very happy on Linux, and may not even notice if you switched it up without their knowledge (it’s not like MS asked before updating from W10 to W11 overnight).

To be clear, I’m not saying to go and install Linux on people’s PCs without their consent. I’m just saying that a lot of people do everything in a web browser, and could switch over seamlessly.

Wine runs most windows applications better and more stably than windows does.

If this is true for Rhino, I’m gonna try it this weekend…. I’ll have to dual boot for games, but I can accept this.

Can’t believe nobody has mentioned Linux as the antidote here yet. Or BSD, if you insist.

the thing is, even with the “average user friendly” distributions, people don’t want to switch because they’re so brainwashed by “big tech.”

They don’t want to switch, because they would lose access to all the closed source software they want. Linux does not support the distribution of such software because the community is ideologically biased against anyone not giving up the source code for the community.

And the reason why there will always be more and better closed source software for the users is because they’re paying for it. The providers of the software are competing to gain users, so there is an incentive to do more and do better rather than just do whatever pleases yourself as a developer.

Engineers of all sorts, left to their own devices, are happy to use whatever convoluted concoction they come up with, because they are experts in their own fields. Users are not, they demand more, so the developer driven open source community is not as well suited for mass appeal.

sometimes paid software is better than open source alternatives, sometimes. especially certain niche applications. though this is getting more rare. i wish linux was more open to this and create better frameworks for closed source software. you cant expect every company to be like valve.

I’ve been using Linux exclusively for 20 years because Linux software is better than the commercial stuff. Furthermore, I can fix bugs and add features that a commercial developer has no interest in because only one person is asking for it.

This started with the Linux version of the Matrox Marvel video capture program being better than the Windows version. I fixed a printer driver and a bug in an antenna design program. I made a plugin for gimp with capabilities not available in any other image program (It’s inconvenient and not very useful, but that’s not the point.) I modified MJPEG Utilities for better noise suppression.

About half of the software I’ve purchased has been defective or obsolete within 2 years of purchase.

You have never had engineers as software customers/clients.

They bitch almost as much as teachers, but engineers have useful suggestions.

Harder to ‘baffle with bullshit’.

Well said, sir. Well said.

Hmm, not everyone in the Linux world is Richard Stallman, browsers on Linux will ask to install Widevine so you can watch Netflix etc. Proton from Valve makes running many Windows games easy (Wine can potentially do that for other software). I would assume most people don’t want to switch OSes because installing an OS is not terrifically easy (they likely wouldn’t be able to install Windows without some help).

Another dimension of locked-down-edness that doesn’t come up here is access to the command line and being able to write and run your own programs; on macOS, dire as things are getting, you still get Python and Ruby pre-installed, which is great.

Proton is a Windows compatibility layer forked from Wine. In other words, to develop closed-source software for Linux, you basically target Windows and hope that it’s not terribly buggy for all the Linux users.

But enough of the people who matter, are, or they don’t care enough about closed source software to make the effort to support it. “I don’t need it, so you don’t need it.”

” on macOS, dire as things are getting, you still get Python and Ruby pre-installed, which is great.”

Ugh. That reminds me of the old MS-DOS days and GW-BASIC. Sure, you can write whatever program you want. But if you pour hours and hours into something and then think you are going to share the results with anyone… well.. only if they are like you, geeky enough to fire up an interpreter to run your code.

BS. There is no Linux distro where one can not install proprietary software if they chose to.

The problem I have found is that libraries change and while OSS often keeps trucking along on the new libraries with just a simple ./configure make and make install (or better yet, just an update from your distro’s pre-compiled proprietary stuff just breaks.

That’s not the community throwing up a purposeful roadblock. That’s just a community enjoying it’s freedom to innovate without maintaining binary compatiblity that it’s open model grants it.

True. Assuming that the software exists in the first place.

It kinda is. If you refuse to standardize and keep changing and breaking things knowing that it makes it practically impossible to distribute proprietary software, that counts as a choice.

There’s no real contradiction between freedom to innovate and standardization – that’s just a red herring by people who don’t want to bother supporting other opinions in the community, or don’t like proprietary software and are making conscious choices against it.

The main problem is that beggars can’t be choosers. The users aren’t developers, so when the developers don’t care about what the users want or need, it creates this insular community that claims to be open but it’s actually just my way or the highway.

I don’t even know why it’s called a community if it’s really based on “I’ll do it if it pleases me, and ignore it if it doesn’t.”. If the “open model” is really just “got mine, screw you”, then what’s the point?

If you’re ignoring the users, is it really open or just open to you?

if you know how to get 3d studio max 2014 to run in linux im all ears? so far this is one of the handful of things that alludes me and keeps me on windows. i think its the drm, as it tries to run, but cant get past activate. when your license has a four+ digit price tag it would be nice not to be told to just use blender.

just switching over is not exactly easy either, my attempts to replace photoshop with gimp will allude to that. instead of doing the thing my hand knows without consulting my brain im cursing at the thing trying to find an option that doesn’t exist. kcad was at least easy to pick up after using eagle for years.

It’s the comunity not giving a sh×t about the average user.

I’ve been a PC user since I first soldered an 8088 on to a board. I’ve been using Linux off and on since it existed. I’ve make my living in PCs and embedded development for decades. Yes I’m an old fart. But I’ve used almost every kind of computer and OS in the last 40 years. Linux is finally living up to its promise as a well rounded OS. But it still frustrates me far more then windoz.

And outside of the server world, most professional tools just work better on Windows. Take IAR, it’s is windows only. And yes I’ve used GCC, but IAR produces smaller faster code.

No way in hell I’m going to try to support my wife or mother or non-techical family on Linux.

Well, I am a techy who has been trying to switch to Linux for 30 odd years. And I haven’t made it yet. Too many deal breakers and it is still easier to run Windows and turn off ads, telemetry and bloatware.

Do I have a Steamdeck? Yes. Was I installing HoloISO on multiple systems a couple years ago? Also yes. Do I still need to try Bazzite? Yes.

All kinds of Linux problems make me give up. First of all was CRT monitor refresh rates being stuck at headache inducing stock refresh. Then I couldn’t run multiple monitors properly, then it was not having apps and game support. Last thing I think was hybrid CPU cores and VR support.

I’ve been using Dos/Windows for 38 years now, and it isn’t so bad because I like pushing what the systems can do, and find a lot of ‘going backward’ every time I try Linux. It’s fun no doubt, and I still dabble.

Well way back in the CRT actually being used era Linux was trickier, and you had to write into a config file carefully IIRC as blowing up your CRT was quite possible if you were careless. But now everything is done with EDID 99.999% of the time it will just work at any supported by the display setting with the easy GUI (though manual configuration forcing behaviour is possible).

Multiple monitors has been working flawlessly forever… I have no idea how far back you have to go for it to be even clunky and hard to configure, personally M$ was more annoying on that one to me (pretty sure it was a driver error that M$ kept reapplying automatically on me).

app and games support is at least even now still somewhat valid – but you wouldn’t expect the developer of a Wii game to make it run anywhere else, so unless they want to… And Linux will actually run easily more apps and games now as all the old stuff Windoze doesn’t support any more WINE does. So its only the modern games, and mostly only ones that have taken deliberate pains to not work with Wine/Proton that really get in the way.

VR did keep me booting up a windows VM with passthrough GPU for a while, but I’ve not needed to do that for at least a decade and everything I’ve tried in VR just works… (When the computer with the VM setup died about a decade ago now I never set up the VM or even bothered putting in the two graphics for host and VM in the new one as I hadn’t found a game or VR problem that made me boot it in ages anyway)

Not saying sticking with what you already know isn’t easier, as what you already know is always easier (though M$ is enshitifying to the point that won’t be true much longer I’d suggest). Nor that you should really switch if you don’t want to. But it is a small learning curve at times, and often no effort at all as the regular user focused Distro’s will work and feel very comfortable. (Though I’d suggest don’t use Gnome if you want to feel windoze like)

I guess I just have too much ADHD, and like I say I push Linux hard to see what it can and cannot do. I’m very familiar with creating and using local windows accounts and de-bloating though, so I’m sure I experience maybe 10% the annoyance most do. As I said, every time I think of switching to Linux the barrier is too high for what I do: try all the latest stuff, hardware and software, in an ADHD frenzy. Linux does not stand up well. I recommend PepperMint, Mint, PopOS!, Ubuntu for more ‘casual’ compute needs like office work, browsing and emails. Most people I know don’t need a 50×0 RTX card to support a VR headset beta features on a game released last week. But when I’m in the mood for that I always pick Windows.

We can hope Bazzite gains some traction, as they seem to have a lot of hardware patches that get mainstreamed very quickly. As an example I would have used it on the PS5 APU server blade I wound up with, because there was only a beta linux driver available and it was deprecated. Bazzite picked up the patches to make it work and rolled them in. Might be the best bang for buck gaming system out there right now. Just need a blower fan and a 12v ~300w PSU. Blades can be found for $50-100.

Linux great, but Microsoft covers more ground with more cohesive GUI. More things to more people. Like a Toyota Camry. You might not find it sporty to drive or look at, but it really covers 80-90% of the population’s needs.

Sound more like you just haven’t tuned your superpowers on blasting through the roadblocks into a Linux compatible one to me. Not that should if you don’t want to, but getting around M$ that actively wants to stop you having a useable system the way you want it is IMO vastly more work and more annoying than setting up a Linux system.

That one got me laughing, as M$ doesn’t understand cohesive GUI, and hasn’t for eons. It is just the most familiar GUI to you – most Linux GUI have far more cohesion to themselves (there are just many of them with somewhat different ideas). For instance MS splitting all the configuration stuff they actually allow users to play with into did it get up to 4 unique locations? with for good measure many things only existing in one of those locations so you’d have to try them all! (Or cheat and not use the GUI at all).

Perhaps the word they were looking for was “comprehensive”.

I’m pretty sure I was using multiple monitors in Linux before Windows even had that ability.

i found windows 11 had a non substantial amount of config post install. win7 i could just use stock without changing any settings other than low hanging fruit control panel items. didnt need to mess with the registry or the command line. now there were at least 20 line items i had to do for windows 11, half were either command line or registry. so its getting to the point where a linux setup is just easier. thought i made some headway when i got winamp to run on my steam deck. linux gets better all the time, where as windows has peaked at 7 and is going down hill fast.

The software I use for a living does not exist under Linux and there is no equivalent.

I hear this a lot, and sometimes is actually true. But I’m still curious enough to ask what software you use and need.

I’m not the original poster, but I use LightBurn a lot and about a year ago they dropped linux support.

This was for licensed and paid professional sofwware. Linux support is frozen at 1.7, while windows support is 2.07 and actively supported.

When I first purchased a laser I reviewed the available software packages, and chose LightBurn over RDWorks because RDWorks only runs on windows.

So to answer your question: RDWorks and LightBurn only run on Windows.

Now the natural follow-up, what about WINE?

Yea, I knew about LightBurn — Linux supportability came up during a job interview last year. I declined to go further with that company because they really wanted a solution that just wasn’t happening..

ive yet to get my copy of 3d studio max to run in linux. its an old version (2014), but it still activates and i still use it. ive tried to get it to run on a lot of distros and compatibility layers. so far nothing has worked. theres blender but then i lose years of muscle memory and workflow familiarity.

Indeed, a very valid concern. Though given the modern trend of you will own nothing and must pay rent to keep using our software it might be worth learning something that won’t do a rug pull on you and will continue to be supported…

But there is no denying learning the new way to work after deeply ingraining the other is hard, by far the most offputting thing to most folks in FreeCAD once you talk to them about why they don’t like it – they start with a ‘missing x feature or can’t do y’ because it just doesn’t work as they expected, but it probably can, and usually easily it is just different.

IAR Embedded work bench. IAR has command line tools for ci/cd, but not the IDE. And I’ve used gcc, but IAR produces smaller faster code.

Many users are content to use the OS supplied with their PC (typically, Windows) and the apps that run on it. Others want a less flexible but cleaner experience, and are willing to pay for it (most of my family) and choose Apple’s walled garden. A small minority want maximum flexibility and minimal interference from the supplier of their OS, and choose a Unix-like os (BSD, GNU/Linux, roll their own).

I prefer Linux (Mint) but I realise I’m in a small minority. At work, we were forced into Linux as an OS for our embedded GUIs, since Microsoft was undependable and unaffordable, and the proprietary real time OS were not to our liking.

Horses for courses. Every option has its advantages and drawbacks. None of the major OS vendors are on the side of the consumer (though Apple makes a better effort than Microsoft at this)

First a phone (to me) is a ‘phone’ . Never download ‘apps’ for it other than what comes with it. Use it for calling, texting, pictures. If I want to run programs, use multi-media, the laptop and PC are the platform of choice. If I want to write applications, the PC, SBCs, laptops are platforms of choice.

Second use an open OS like Linux or BSD if you don’t want walled wally in your face forcing you to their way of thinking. You are responsible for security on your ‘device’. Run any app you want. The way it should be. The solution is clear… and easy. So instead of complaining, just switch. Life is much better on the Linux and BSD side, and forget Apple and M$. That ship as sailed. I do miss the good o’ days with DOS and early Windows, but that era is behind us.

For me a phone is an at-a-pinch computer for when I’m out and about away from my computer. It’s annoying as heck to use, but it’s better than nothing. SSH client and a browser being the most used apps.

I got a Fold 2 a few years ago because I spreadsheet, cross shop all kinds of parts and due to be semi-bedridden or standing outside when I shop the ‘phone’ is better than a PC. (Literally a bigger screen than my first tablet).

Should I get a chording keyboard and wireless heads up glasses? Probably, also need a trackball ring possibly.

Still love PCs, just a pain to pull it out and find a desk.

Entities like Google, Apple, Microsoft, can keep their monopolistic practices and keep tightening the thumbscrew, because there’s no realistic alternative for the users.

If you want the vast library of software provided by closed-source for-profit software vendors, you’re not going to become a Linux user because those vendors cannot operate there, because these platforms are too heterogeneous and refusing to standardize to support closed-source software distribution.

They’re not going to give you anything when they can just put their software on Google Play and reach billions of paying users without jumping through the hoops and hurdles you’re trying to put in front of them to “encourage” them to play the open-source community game.

If you want the situation to change, the users have to be able to vote with their feet against Google and the rest. You want to create a truly open platform for all kinds of software and business. As it is, there’s no pressure of competition, so however much you’re complaining, the ideological balkanization against the commercial software ecosystem is just tilting at windmills.

Of course you can just make more open source software to replace the market. Yes, absolutely, do that: make it as comprehensive, good and as varied as the closed source competition without being able to sell it because you’re giving up the code for anyone to copy.

I’ll be waiting.

People who use their notebooks just run web browser didn’t switch to Linux even though their web browser was there.

People who claimed netbooks were underpowered junk and Linux was not enough to replace Windows keep buying Chromebooks.

People who argued that repository idea is too complex for them, now use Play Store, App store and what ever ChromeOS serves.

People who found OpenOffice and Libre Office not sufficient enough for their needs jumped to whatever alternative was there on Android telling how good is to have something so simple – not such Behemot like MS Office.

I think there is more than just availability and price.

Except that most software runs better and more stably on wine (or proton) than it does on windows in the first place.

There are plenty of closed source for profit programs that work on Linux, pretty sure even a few that target OpenBSD despite its really really minor userbase and that has been true for eons…

If YOUR particular software company of choice has not made that decision to actively support Linux, or even just make sure to target WINE/Proton so the windows app will just work is a real problem for you as the user. But there is no real problem for the developer with creating closed source applications for Linux – pick any distro at all as the one support and say so, and all the users will find it works flawlessly on just about any other with a few posts in the support forum ‘oh x distro is missing y in their build of z – but you can get the patched version this way’ or ‘needs a feature in kernel 6.2 so get the upstream kernel your LTS distro hasn’t moved to’ etc…

Also before Big G dropped the ‘Don’t be Evil’ and started acting this way Android itself was a perfect example of a huge variety of closed source sold for programs can work on the open and rather varied platforms – Early Android is a pretty big development ride in hardware and software changes, but was rather open and full of paid for software… The only difference between Linux and Android is Google offered an easy distribution path shouldering most of the costs and took a cut of the sale, so no need to open up your own web store and authentication system etc – rather like Valve does with Steam for the game developers. Which is also a good example of a closed source (at least largely) for profit company that does and has for some time worked on Linux…

Except for the fact that every distro does desktop integration slightly differently and it keeps changing all the time. It’s not “fire and forget”, you have to keep updating and re-packaging continuously. Now it’s flatpack, tomorrow it’s snap, next week it’s something else, but you also want your software to be available in the repositories for easy access.

Let’s say I want to include a system tray icon that works out of the box regardless of what DE the user has. How many versions would I need to write to reach 90% of desktop Linux users? Where would I put or how would I distribute it to achieve that?

Honestly, I think Flatpak’s becoming the de facto standard; Snap’s been on the fringe for a few years now (certainly not “tomorrow”). More proprietary apps tend to be on Flatpak. A lot of the beginner friendly distros have app stores that allow users to easily install Flatpaks, from what I can tell.

Also, the system tray example doesn’t really work; whatever GUI toolkit you’re working with usually provides that.

However, your point stands that standardization is still lacking in other areas, especially with Wayland compositors, though Pipewire seems to have at least made Wayland screenshots more standardized. However, many applications don’t need all of the less standardized features; so long as its GUI renders correctly and it can save files, it’s fine.

It is pretty fire and forget as almost everything meant for one desktop still works flawlessly though might look a little out of place on the others. Also you missed the part where I said PICK ANY DISTRO as the one you officially support. That is then a very static target, likely as stable if not more stable a target than M$ assuming you pick say Debian or Ubuntu LTS distros…

All you have to do is support functioning on ONE MEMBER of Linux ecosystem at all and the users will figure out how to make it work on all the others for you – nice if you have a support forum for them so the users can ask each other and quickly search for existing solutions, but even that is optional.

But suppose we want to. Instead of pushing updates through a million different channels, we distribute it ourselves so we can ensure that everyone has the latest version. Can we manage that and still reach all the users?

As you point out, Valve is essentially maintaining a platform on the platform. It’s a shim between Linux and the games they’re offering, so they only need to keep supporting one program across the whole landscape instead of every game individually. Maintaining one program to keep support for a myriad makes sense, because the relative effort to do that is small.

What if we’re a software vendor with only one program to sell? Does it make sense to keep shimming it in to all the different variations of Linux out there? Do we need to create our own platform-on-platform?

The better question is, why doesn’t “Linux” offer such a shim for people interested in distributing closed-source software across the platform? Define a standard and stick to it, and outside of that standard do whatever you want.

Oh right, they tried, and it never got anywhere (Linux Standard Base), because everybody wanted it to be different and they were all afraid it would become a de-factor standard for all Linux software, depriving them of the choice to do their own things.

The argument as I remember it was, if there is a standard then people would start to make demands and complain if a developer was not following it, forcing them to do “unnecessary work”. As opposed to tossing their work over the fence to be other people’s problem if they want to make it work on their systems like they’re doing it now.

Only problem is, for closed-source software targeting Linux directly, since there is no standard it becomes the original developer’s problem to get it working under all the different permutations of Linux. That is what demands these makeshift shims like Wine and Proton to exist.

As i understand there currently are a variety of cross platform binaries for most linux distros available. inkscape, for eg has one. it’s filesize is huge, because all the older libraries are rolled in.

The demand is clearly there, because myself and others don’t have the grit to sort out compiler dependencies and version conflicts.

Like freeCad (and Inkscape). I just pull the latest appImage, change permission to make an executable and off an running.

If you want to do that now then you need to be on Linux! As Big G is saying “NO! ye must pay us our cut, and a fee just for the privilege of being in the system to pay us that cut!” and M$ has been trying to go the same way with M$ store for ages (though at least for now you have got the ability to go around).

Nothing at all stops you from having your own web store and auth system, or updater – for instance Fantasy Grounds both the now obsolete Classic and new Unity powered versions have supported Linux to some extent or other, and it is just a single program, and they do indeed have their own web store, updater and auth system. (Its also a great virtual TTRPG software with a more user friendly buisness model than any of the others when I bought it – really flexible to multiple rulesets including purchase of licensed system books with great integration into the lots of helpful automations you can use if you wish but that don’t get in the way if you don’t).

Which means you’re still targeting Windows, essentially, and so what Microsoft does, you have to do too – if you can. If it becomes a threat to them, they can make chances that break cross-compatibility and you’re back to square one.

The idea is rather that you would provide your own platform that is just as easy to target, that is not tethered to the corporation.

If M$ breaks something so a program doesn’t work in WINE that program is almost certainly also broken in Windoze by the change. As breaking a translation layer really means you are no longer speaking in the same language as all the software that did once and is supposed to work with you does…

And of course creating that new language with the intent to break the translator and lock down new programs written with it just won’t really work – all you can do is work hard to make it difficult for WINE to implement the Klingon language translation layer, which also makes it harder for the developers to develop with it… So they’ll all stick to the old system anyway.

Remember embrace, extend, extinguish?

You don’t break compatibility with the old stuff, you break compatibility with the new stuff. You add something that doesn’t work on the other system (i.e. Wine) and all so when your users update to the next version, the people on the other system are left behind.

It doesn’t need to be a new language, it may also be something like a security key or a signature check that Wine can’t replicate because it isn’t Windows. Make it, “This program will only work on Genuine Windows ™” and that’s it. Accept no substitutes.

That cat and mouse game is very hard to actually lock WINE out of following along without effectively locking the door on all the 3rd party software companies you want to work on your OS, as the big reason so many folks haven’t moved already is software x doesn’t have official Linux support and I use that software. Mess with that and M$ will just shed users as they have forced the users to change anyway – which is why the M$ store that is already trying very hard to be that just hasn’t gone anywhere much, everyone is getting their applications outside of it.

You know what console has no lockout chip and lets you run whatever you want? The GameTank ;)

Atari 2600.

Fairchild Channel F.

Intellivision.

Colecovision.

“Run whatever you want” might be a bit of a stretch, though.

In the days of the early videogame console it probably made sense to be more locked down – its a bit of a symbiotic relationship between the game developers/publishers and the hardware folks, as they have the choice of sell the console for a reasonable profit on the hardware, and thus get very few sales, so the game developers will also get fewer as there are so few potential clients or co-operate with safeguards to grow the user base. Adding in those safeguard features to make it difficult to void that mutually beneficial arrangement is logical and fair enough, even if annoying it isn’t really abusive to the users either at the time.

But today….

Points to original north American Nintendo console.

Points to price fixing settlement about ten years later.

But with linux phones now and in the future will this even matter in the long run? When the world moves away from apk for linux possibly then maybe they will change there tune from lost market share is my guess. When some one pulls one way then other will pull the exact opposite, it’s human nature to go against the grain or find the grain that smoothest to work with. Theoretically a linux is could run a vm android os and emulated any android os that still can use homebrew apk. Theres always cracks in the cement where the plants can grow through

web-apps might be the linchpin for Linux phones. Developing native apps is a pain in the butt, so much so that major apps like Uber Eats are just web pages in a wrapper. The more common this becomes, the easier it will be to daily-drive a Linux phone.

hahaha now we’re trying to make this nothingburger of a footnote to android’s decay and portray it as an epoch-defining moment for computing. nuts.

Still at the propaganda machine I see

“yeah you’re complaining about something relatively harmless that google is doing when in fact they’re becoming across the board as bad as microsoft ever was” is sure some propaganda

Decay? Android has 75% of the global market share for moving devices. It’s kind of a big deal, as is this change in policy.

25 years ago, well over 90% of the global market share for mobile devices wouldn’t let you run anything other than stock software. You couldn’t run add-ons of any kind. That was the day freedom died. /s

“[Console makers] locked down their hardware tighter than a bank vault, and they did it for one simple reason—money”

… whereas the people in the next paragraph, modding their consoles to play pirate games, were motivated by the sermon on the mount?

Hey I’m not siding with big business here, but the conversation gets silly if we uncritically frame everything as “stupid greed vs. righteous wisdom”. Console licensing does make the hardware cheaper and more viable; iOS sandboxing does make it safer and easier to get apps on people’s phones. If your ideal Linux smartphone doesn’t let your grandma safely install apps without your help, then you’re not making a serious counter to what Apple is offering, imho.

I think we miss two important things by having the politically vacuous version of this argument:

1) bootlegging is not anti-capitalist, it’s just a boisterous way of participating in the market (“I won’t pay $15/mo for Prime, but I’ll pay $50 for this illegal fake Fire stick; your move, Amazon”)

2) if you want to move tech outside of capitalism, that means building up grassroots tech as a viable alternative. I think we should want that. But step one has to be honesty about where big tech has set the bar. I see people insist that Apple’s overall UX is terrible, and everyone would prefer Ubuntu if they weren’t so brainwashed, and I think “welp, enjoy settling for a worse ecosystem that doesn’t value good work”. Not that I’ve done anything heroic about this.

man i’m riffing off topic here but “I see people insist that Apple’s overall UX is terrible, and everyone would prefer Ubuntu” got my wheels spinning

I don’t imagine anyone would prefer Ubuntu. But when i go voyaging through unfamiliar systems, all i find is atrocious UX. Had to use my kid’s school-issued iPad once because he ‘accidentally’ set an alarm for 4am. The UI to change the alarms was unbelievably atrocious. It was never scaled to the big screen of the iPad, so it has tiny text in one corner and a collection of tiny icons in the other corner, and a huge wasted space in between. It’s hard to click or read the tiny things, and all that wasted space! And i couldn’t figure it out — it turns out, one of the tiny meaningless icons toggles a mode, and in one mode you can delete alarms and in another you can’t. A complete disaster of UX.

A couple days ago, i helped my wife with Excel 365. To its credit, it offers a new feature “dynamic arrays”, which makes it actually genuinely usable for the first time in its history. For decades, microsoft never bothered to figure out how people would do relational database tasks with its core formula language. But if you have a typo, it pops up some clippy sequel who tells you things you don’t want to know. It never got close. I would have been better off with an opaque window that said “syntax error”, but with a little sophistication i think it could have detected the problems we were having…like, unmatched parenthesis isn’t exactly a never-before-seen error. Surely everyone knows that its advice is never useful, why wouldn’t they ever focus group this thing and watch how users interact with it?

And then the real funny thing is, Microsoft documentation for Excel is no good…it’s neither precise and accurate (what i want out of reference documentation) nor intuitive and legible (what everyone else wants). Instead it kind of vaguely waves a hand in the direction of the problem domain. I understand ALSA doesn’t have good documentation because they don’t have a bunch of volunteers interested in maintaining an API manual, right? What’s microsoft’s excuse? Isn’t this a billions-of-dollars product??

I’ve got a bunch of complaints about Android (which i’m very familiar with) of course. But it’s just stunning to cross to the other side of the fence and see the grass is all brown and there’s no attempt to hide it.

I genuinely absolutely do prefer Ubuntu. I have had to use Apple products for work for the last decade, and the UI is so bad that interacting with it could be an afterlife punishment. I’m constantly baffled about why people like it. All I can come up with is they prefer pretty rounded corners on their UI windows above all other considerations.

I think ‘regular users’ are just correctly discerning vague contrasts between different flavors of brown, dead grass. Microsoft, Google, and Apple have all seen to it that every consumer device represents the culmination of decades of braindead UI choices. So if every device you use is constantly going to screw you over, you have to decide which unpleasantry bothers you the most. For a lot of people, i think Apple really is much better than Android or Microsoft. Whose fingernails on the chalkboard sound worse to your ears?

And you’re right – sorry – i don’t mean no one prefers Ubuntu. I just mean, i don’t expect it to be a significant factor for end users any time soon. Depending on what you’re doing, there’s upsides and downsides, but for most people i think any of the popular Linux desktop environments pose unique downsides they will reject. (obviously, i use Debian w/ X11 + fvwm + xterm + chrome + pdf viewer, and avoid almost every other intrusion of GUI into my desktop experience)

And I use KUbuntu (KDE) LTS for desktop/workstations/laptops. That to me is the beauty of Linux UIs. Pick the one that fits your work flow the best. None are perfect (or we’d all be on it), but you have ‘choice’! And LibreOffice, FireFox, Chrome, etc. all run on any DE you pick (that I know of)… Heck, you don’t even have to use a UI if that floats your boat…. And I do, using SSH into most of my RPIs. KUbuntu has been rock solid for my use. Why I stay with it. RPIs of course run PI OS as I use them for more than a Linux platform.

I see the (partial) solution being Windows 11.

Meaning, it’s so bad that average users (and a lot of governments) are finally giving Linux some serious thought, especially as Mac has become so specialized that it’s not in a position to directly compete. (Wine on Mac sucks, if I’m being honest, so you’ve mostly got web browsing and some specialized productivity apps that were the buyer’s main reason for getting a mac and not another computer.)

People are seeing the problem.

Now we just need a new network that’s so wild west we can all jump ship if necessary.

So far as I know, Meshtastic and the like can’t handle the type of traffic I’m talking about, … but it’s a step in the right direction.

I guess we’ll see how it all goes, but I’m betting that if people are pushed too hard, they will rebel.

Thoroughly understand your idea about the need for a new “wild west” infrastructure for a better internet. Meshtastic is great, but apart from not being suited for much beyond text content by its design, it simply hasn’t the bandwidth to connect up billions (or even merely millions) of people, even for simple SMS-style communications. I’ve seen lots of wild hopes for a new wild west, but very few discussions of the exact problems which actually need to be solved to make such a system work. The closest thing I’ve found is the paragraphs with bold headings towards the end of the following article.

https://dailysceptic.org/2025/08/16/the-online-safety-act-exposes-how-fragile-our-overly-centralised-internet-really-is/

When people talk of a new parallel network to the existing internet, it’s really essential they think about all these sort of problems, without consdering them any new network just withers away with lack of users. Hint, infrared line-of-sight data links might be a big part towards getting bandwidth for the longer ranged parts of a decentralised web.

Apple’s GPTK through Heroic for gaming is actually surprisingly stable and performant. It’s also entirely off-label, right? You’re not supposed to be able to do that. Apple doesn’t want you to know you can, because they don’t make money if you don’t buy from their publishing partners.

i wouldn’t want to run code from un-trusted sources, like microsoft, google, apple, etc.

if your business practices are exploitative, and you dont dont treat your customers right, how can they ever trust you. then all those certificate databases and tpm modules mean a hill of beans.

Google’s security explanation would be plausible if their own app store wasn’t filled with malware.

I’m an iPhone user, have been since my first. I also run a couple flavors of Linux on a handful of machines, and I’ve got a Windows 11 gaming desktop.

The thing that bugs me about this whole situation is that the bargain has always been “If we lock down this platform, we can provide you with higher-quality experiences that make it worthwhile.” So I couldn’t play Runescape on my iPhone 4S or my original iPad Mini, but I at least had a guarantee, of sorts, that the software I could run would be of a substantially high quality that I wouldn’t miss it on that device. And for a while, that kind of felt true.

Steam had a similar promise for a long time – Valve was incredibly restrictive about the content they allowed on the platform until they weren’t, and now it’s flooded with porn games and slop someone threw together in Unity hoping to make a quick buck.

The bargain, the loss of freedom, was always based on exclusivity and curation. A walled garden just feels cheap and claustrophobic if the garden’s full of dead grass and garbage. Apple’s guilty of that too – there are plenty of apps, even relatively large ones, that barely work anymore. It doesn’t matter, people will pay for them anyway and Cupertino gets their tax. Seems like Google learned the same lesson.

The only thing I really use my phone for these days is Discord chats, email, and calling my mom. So much for the promise of curated, high-quality software in a convenient app store.

Heh my favorite game lately is Rally Fury on Android TV. And as far as i can tell, it’s just the most basic car-themed skin on top of Unity. I’m curious how it stacks up compared to “slop someone threw together in Unity hoping to make a quick buck.” I kind of thought that was the point of Unity and i love what it’s accomplished for me!

So many unhappy people; restrictive application installs on iOS and Windows and Android.

Blame lawyers:

They are constantly attempting to secure Cla$$ Action suits against Apple, Microsoft, and Google (not excluding other tech companies.)

Building the hardware or OS and providing an easy hosted 3rd party application installation methodology for the general public open these big-dollar companies to serious monetary risks.

The companies do make billions off their respective app hosting stores,

— BUT —

As mobile devices expand to cover use by pre-teens to the elderly, locking down the hardware and critically critiquing software is simply inevitable to avoid punitive attacks from money hungry lawyers who are constantly getting better at winning jury cases (or securing big dollars out-of-court).

On the Android API concern, I blame Amazon and their Kindle OS.

Finally Linux GUIs … I have a favorite, betcha you do too. I also have a favorite pairs of shoes.

Win-11/Linux/Android applications?

Microsoft has depreciated the Windows Subsystem for Android but WSL has worked rather well for me on Win-11 24H2 but I prefer raw Linux as there is always some “tuning” and hacking WSL config to get things to work completely.

I view such tuning as wasted time.

Non-commercial Linux users who get the OS for free are unlikely to want to pay a lot for any Linux app and paying for app support is even more unlikely.

Revenue streams for Linux apps is almost solely in Commercial space.

WASM, PWAs, and emerging tech like Project Fugu are likely to be the tech that will finally provide cross-OS compatibility from the end-user’s prospective; working exactly similar cross-compiled native software products. With the current processing power of recent PCs and ample RAM memory, the penalties in performance will not be noticeable to the user. However, fast-internet is still not universal, so latency will require careful application design (Microsoft likely is ahead in this area of design due to the experience with their 365 apps.)

Finally …

“Modchips sprung up as a way to get around that problem, albeit primarily so owners could play cheaper pirated games.”

Humans seem to have a way if rationalizing “stealing” as a reasonable action; whether it was using Copy II Plus on Apple disks or making illegal copies of Windows XP or Microsoft Office.

Sadly, the leaking boat we are in is partially our own doing.

Is it any wonder that businesses work hard to implement tricks to secure their intellectual property? Yes, not a popular end-user opinion.

This is the reason I refuse to get the Vision Pro. I dont want the “next paradigm of computing” to be a walled garden. I am to blame for accepting this with the iPad. It was too easy with the phone, but I let it slip with the iPad. I recently took away the kids iPads and I’m making them do everything on a laptop. At least now if they want to play a game they have to learn how to use a controller.

My kids recently turned 6 and 8 and only use Ubuntu for many years now. They play with blender like I used to play with ms paint. Then we printed it out. Hell no on ipads, what are parents thinking? Get them early then they dont sound like Dude with a million excuses why Linux is so terrible lol.

pff .. this is just nostalgic piffle or a golden era that never was.

Back in the dos era? ..yea bac in the does era Microsoft put in special code to keep users from running Dr Dos specifcally targetting that companys product. Later Java fought for a place, company’s fought allowing Linux to exist. People have been jailbreaking Android and Apple devices for years not because they were paragons of openness, but because they’ve always had attempts at coercing user behavior. This is just one more iterative step in the attack defend cycle we’ve been locked in since hacks were pubished in Compute magazine and gamers worked to put the game of the week up on IBM mainframes, Cyber NASA computers, and Crays.

pff .. this is just nostalgic piffle or a golden era that never was.

Back in the dos era? ..yea bac in the does era Microsoft put in special code to keep users from running Dr Dos specifcally targetting that companys product. Later Java fought for a place, company’s fought allowing Linux to exist. People have been jailbreaking Android and Apple devices for years not because they were paragons of openness, but because they’ve always had attempts at coercing user behavior. This is just one more iterative step in the attack defend cycle we’ve been locked in since hacks were pubished in Compute magazine and gamers worked to put the game of the week up on IBM mainframes, Cyber NASA computers, and Crays.

I think that more than half the time when I sideload on my Android phone it’s via adb rather than directly on the phone. It’s more convenient to browse the web on my laptop, download and use adb. As long adb is unaffected, it’s not a big deal to me, though I dislike the direction Google is heading.

How are you going to lock down the phone and force everyone to install a government mandated app if you allow app side loading ?

Just part of the mission.

Anyone using Linux must be a terrorist or subversive.

it,s my phone i make with i want with IT !

it,s my computer i make with i want with IT !

Michael “Grab a beer this is going to be rough” Nickles predicted this in the 90s in his PC Report books. One of the many reasons in 2001 i installed Mandrake on my work PC an never looked back.

Why not find a way to run unapproved apps in some kind of sandbox environment with configurable permissions?

With smartphones we can restrict apps from accessing files and peripherals and limit their idle power consumption.

Why can’t we do the same with PCs?

Some apps in Windows require admin mode to run. And in Linux almost nothing works without sudo. So with desktops it’s pretty much all or nothing.

Web browser is the sandbox :)

(fwiw, i rarely use root on linux)

With windows they just decided that since Android is beating them they would become an android OS.

And so yes if Android becomes locked down they will follow for sure.

And incidentally, various flavors of Linux also move in the direction of lock-down, and I’m preparing for a future where I have to live without tech. Regardless that both the government and all the big corporations are already forcing it on you.

I’m not aware of any Linux flavour that is actually locking down at all. There are some that default to being immutable like SteamOS so the user can’t as easily screw themselves over without effectively opting into and accepting that risk first. Which IMO is a very good thing to have as an options as it gives even a technologically inept system wrecker something they can just use and not screw up by accident in their bumbling. The ideal system for the Gran, Toddler, or “Political scientistic” in your life.

But even those immutable ones have left the door unlocked for you to mess around if you want to – its all a choice left up to you, or if you are not the sysadmin with root privileges to them, who might then bestow it upon you, for you have been given the right permission for whatever it is you are doing.

I haven’t followed closely but hasn’t IBM bought redhat and started trying to turn it into the anti-freedom?

IBM owning Redhat isn’t new, and as far as I can tell other than some minor friction points really not very relevant to anti-freedom type stuff at least. Maybe I’ve missed something but it doesn’t really seem like a real Problem.

The article is a disservice because it fails to recognize why the walled garden was created. The reason was simple – the video game crash. Atari created the 2600/VCS and it was open because Atari never considered third party developers. However a bunch of disgruntled Atari developers left and created Activision. They built their own dev kits and created their own games. Atari sued them and lost. Soon the market was flooded with games that weren’t selling and retailers pushed back. We called it a crash because after that, videogames were dead. No one wanted to carry them, consumers were wary and refused to buy them as they were mostly crap, etc. The fad was over.

Nintendo had the Famicom, but saw what happened to the 2600 and implemented a lockout chip so they could control the quality of the games. Retailers still refused to carry video game systems and games, forcing Nintendo to release it as a digital toy. But toy stores were segregated back then so Nintendo had to choose – boy or girl, and not both.

That’s why consoles started it – to avoid the flood of crap that sunk the 2600 and an entire industry for a couple of years.

Computers with walled gardens is a more recent phenomenon. This originated because Microsoft- the flood of viruses, worms and Trojans flooding the internet affecting Windows was incredible and dumb users running email attachments was popular. IT departments wanted control – they didn’t like users running anything and causing havoc on their networks.

Android openness was also a problem- early Android was plagued with information stealing apps in the Play store. Even innocent apps could cause problems- T-mobile was brought down by an app misbehaving. It’s a reputation Android still has.

TBF while most videogames sux but Call of Duty 1 (2003) made by ACTIVISION is one of the greatest games ever made, and it’s also educational because it teaches WW2 history. What Super Mario teaches to children? Killing turtles and eating mushrooms.

What are you talking about? There’s a whole section on consoles becoming a walled garden and direct reference to Nintendo wanting quality control.

Concerning Android, the security argument might be more convincing if there weren’t so much malware in the play store