[Sam Ben-Yaakov] has another lecture online that dives deep into the physics of electronic processes. This time, the subject is magnetic transformers. You probably know that the ratio of current in the primary and secondary is the same (ideally) as the ratio of the turns in each winding. But do you know why? You will after watching the video.

Actually, you will after watching the first two minutes of the video. If you make it to the 44-minute mark, you’ll learn more about Faraday’s law, conservation of energy, and Lenz’s law.

One of our favorite things about the Internet is that you can find great lectures like these online, both from university programs and from individuals like [Dr. Ben-Yaakov]. There was a time when you would have had to enroll in a college to get the kind of education you can just browse through now.

Too much math and technical detail for you? We get it. You don’t need to understand all of this to use a transformer. But if you want to understand the math and the physics behind the things we do, nothing is stopping you. Even if you need to brush up on math, there are plenty of similar lectures to learn about that online, too.

Want a university class that is more practical? We hear you. Prefer simulation to math or solder? We hear you, too.

The ratio of the voltages is the same as the ratio of the turns. The ratio of the currents equals the inverse of the ratio of the turns. All assuming perfect coupling and no losses.

If you consider the case of unloaded secondary, you also need infinite primary inductance for the ratios to hold.

Ideally no power is lost so both are true. If you transform 10v to 20v them the current at 20v would be 1/2 what you draw at 10v but actually is less because real life. This is also why impedance shows through as a square factor. If you prefer math over video: https://www.3phaseee.com/static/docs/transformer-reflected-impedance.pdf

“The ratio of the voltages is the same as the ratio of the turns.” That’s the one thing I thought I knew about transformers then I read this article and thought “Hmmm. So I even got that wrong?”

In simple terms, a transformer turns input current into a magnetic field, and then converts the magnetic field back to output current.

So why can’t we do this with an electric field instead of a magnetic field? What don’t there exist transformers that use electric fields to convert high voltage AC to low voltage AC?

You can do it with piezo materials, using an acoustic field as the intermediate ‘medium’. You can even do it with waveguides at high enough frequencies.

But why can’t you do it at (say) audio frequencies? Say, for the output transformer for a tube amplifier.

You can switch up or down voltage with electric fields, such as switched capacitors or charge pumps. But these methods also require common ground so you lose isolation that transformers provide. If you don’t need isolation switched capacitors can be very efficient.

Yes, those are useful for transforming low voltage DC to an integer divisor or multiple of that voltage, yes. A neat application is taking a USB-C 9V and charging a single lithium cell with it — you can get 25 watts into a battery this way. But it requires high frequency switching and multiple active devices, and limited to relatively low frequencies (like DC) and low voltages that the switching devices can handle.

I’m wondering what the fundamental physics reason is that you can’t build an electric field analog of a magnetically-coupled transformer.

As I understand it, magnetic fields and electric fields have different topologies in space that affect how potentials accumulate depending on path. A charge moving from point A to point B through any number of electric fields ends up at precisely one potential, the difference between A and B. Path does not matter. A charge moving through magnetic fields can accumulate potential differences with each cycle it makes through a magnetic flux loop. Path does matter in this case. A transformer requires some mechanism that can store some quantity of energy and release it at different potentials. Inductors can do this, but capacitors can’t.

the electron on the outer valency ring of the atom is where the charge is located, and jumps to the nearby atom when an electrical current is flowing. if there’s no charge flow, by being next to an insulator then there’s no way of manipulating the charge.

I suppose you could try to use quantum entanglement of two circuits to provide the necessary transformer isolation.

Electric fields are fundamental in transformers. A changing electric field creates a magnetic field and a changing magnetic field creates an electric field.

My other reply didn’t show up, so I’ll try again.

Magnetic fields and electric fields interact with moving charges in different ways. Transformers use magnetic fields as the medium of energy exchange because they allow moving charges to accumulate potential differences with each cycle around the field. This is not possible with a capacitor since the path a charge takes in an electric field does not change the potential.

Another analogy I like is a capacitor is like a rubber band storing energy in tension. An inductor is like a flywheel storing energy as momentum. Transformers are like gearboxes on a flywheel that let you exchange speed (voltage) for torque (current). You can’t do that continuously with just a rubber band.

A couple of things, actually!

Direct analogy: a transformer is an inductive divider (of sorts, but I’ll get to that). An electric transformer is therefore a capacitive divider.

Physical asymmetry: magnetic field lines are always loops. Electric field lines are always* terminated in a surface. Thus, there’s no such thing as mutual capacitance, just a matrix of (lone) capacitors between conductors; this is the underlying explanation of the above.

*Assuming electrostatics.

So the problem seems to be that electric field lines don’t loop and magnetic lines do. What if we make them loop, then?

We can only do that at AC, and then we aren’t electrostatic, or magnetostatic, but dynamic. We have to do both E and M.

So we find it’s actually a category error: a transformer transforms EMF. Voltage is transformed. Current is transformed. A transformer is already the universal V/I and E/H component!

There are other applications, and quirks, derived (albeit sometimes at length, so worth noting by themselves) from the above (or, more formal versions of the above). For example, in RF work, a capacitor divider is also an impedance matching transformer; this works under a narrow-band assumption, i.e., the Q factor has to be greater than the ratio, roughly speaking.

Which, if you’re making a narrow filter, like a chain of tuned resonators, the input and output can be coupled to line impedance (say 50Ω) with a capacitor divider, the capacitance of which resonates with an inductance, forming a resonator of reasonable [characteristic] impedance (Zo = sqrt(L/C)), while permitting a high Q (Rpar/Zo, or Zo/Rser). This is how you avoid using absurd values (like nH or even pH inductors, or µF capacitors at 10s MHz, or fractional pF caps, or µH inductors at 100s MHz, etc.). Coupled resonators will typically use mutual inductance (basically, proximity) to link a chain of them into a filter, and the coupling factor between pairs is given by roots of the filter’s polynomial.

In any case, this can be done without using a transformer with explicit full-voltage (or current) windings, and the attendant strays introduced by all that wire length.

Resonators can also be joined by putting in mutual reactance, for example a large reactance linking between the tops of parallel-resonant tanks, or a small reactance linking the bottoms of series-resonant tanks; but the reactance causes some detuning (raising or lowering the resonators’ Fo), and shifts the cutoff skirts to a high-pass or low-pass dominant characteristic. Whereas mutual inductance is neutral, only splitting poles apart, without shifting the center frequency, or causing asymmetrical skirts (at least, ideally; real proximity in practice, tends to shift a bit of both L and C, but as a lower-order effect).

…RF design is probably one of the worst examples I could go with, huh? :o) Anyway, the fact that transformer action leads to a balanced or neutral change of characteristics, seems just unique enough to be relevant here. I do think there’s a lot of value in understanding AC components at their most detailed; how much effort is paid for that value, is really the bigger question — AC network theory ultimately lies in the land of polynomial roots, linear algebra, and quite possibly dragons; it is a notoriously difficult subject, to be sure.

Thanks Tim. That’s helpful.

I get it. I’ve got 4th year E&M under my belt, back from shortly after the electron was invented.

It’s just fundamentally dissatisfying. I feel there’s a symmetry somewhere I’m missing. It’s annoying.

Is there a kind of transformer that -isn’t- electromagnetic that I haven’t heard about?

I could have sworn I signed up for the memo mailing list.

Piezoelectric transformers may not be common, but are commercially available:

https://www.mmech.com/transformers

Maybe a switched capacitor transformer qualifies? Then it’s electrostatic.

And I suppose if by ‘transformer’ you generalise to ‘conserve energy, but transform details of how it is conveyed’ then gear systems, block-and-tackle, levers, inclined planes qualify in the mechanical realm.

To be fair, computing uses transformers, and many other areas. That’s not me being a dick or pedantic. I’m just implying that once a word reaches a certain level it can’t be seen as gated by older logic. Think about the word Frequency and then Hertz. Or even waves in general. They aren’t binary nor or they this way or that way. I just mean to say this kind of approach helps me immensely over the everything’s moving yet never changing model.

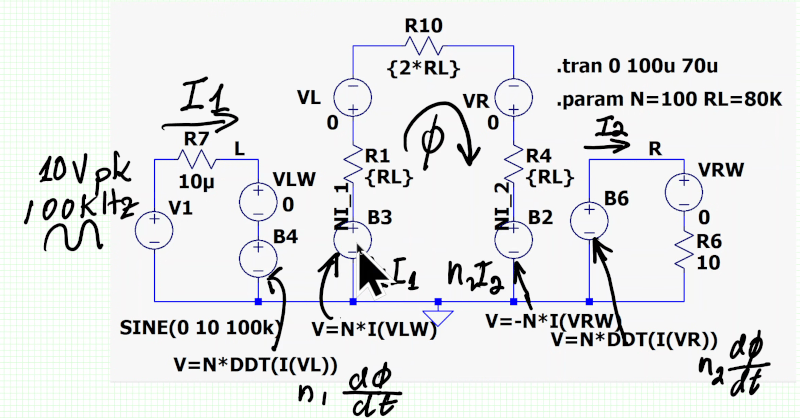

Where are the magentization currents and leakage inductances? Meh this model seems far from what you’ll see “real world” working with transformers.