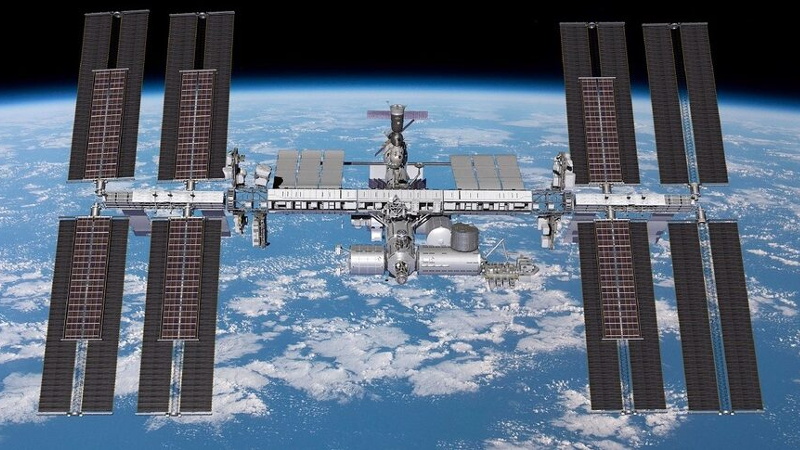

Over the course of its nearly 30 years in orbit, the International Space Station has played host to more “firsts” than can possibly be counted. When you’re zipping around Earth at five miles per second, even the most mundane of events takes on a novel element. Arguably, that’s the point of a crewed orbital research complex in the first place — to study how humans can live and work in an environment that’s so unimaginably hostile that something as simple as eating lunch requires special equipment and training.

Today marks another unique milestone for the ISS program, albeit a bittersweet one. Just a few hours ago, NASA successfully completed the first medical evacuation from the Station, cutting the Crew-11 mission short by at least a month. By the time this article is released, the patient will be back on terra firma and having their condition assessed in California. This leaves just three crew members on the ISS until NASA’s Crew-12 mission can launch in early February, though it’s possible that mission’s timeline will be moved up.

What We Know (And Don’t)

To respect the privacy of the individual involved, NASA has been very careful not to identify which member of the multi-nation Crew-11 mission is ill. All of the communications from the space agency have used vague language when discussing the specifics of the situation, and unless something gets leaked to the press, there’s an excellent chance that we’ll never really know what happened on the Station. But we can at least piece some of the facts together.

On January 7th, Kimiya Yui of Japan was heard over the Station’s live audio feed requesting a private medical conference (PMC) with flight surgeons before the conversation switched over to a secure channel. At the time this was not considered particularly interesting, as PMCs are not uncommon and in the past have never involved anything serious. Life aboard the Station means documenting everything, so a PMC could be called to report a routine ailment that we wouldn’t give a second thought to here on Earth.

But when NASA later announced that the extravehicular activity (EVA) scheduled for the next day was being postponed due to a “medical concern”, the press started taking notice. Unlike what we see in the movies, conducting an EVA is a bit more complex than just opening a hatch. There are many hours of preparation, tests, and strenuous work before astronauts actually leave the confines of the Station, so the idea that a previously undetected medical issue could come to light during this process makes sense. That said, Kimiya Yui was not scheduled to take part in the EVA, which was part of a long-term project of upgrading the Station’s aging solar arrays. Adding to the mystery, a representative for Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) told Kyodo News that Yui “has no health issues.”

This has lead to speculation from armchair mission controllers that Yui could have requested to speak to the flight surgeons on behalf of one of the crew members that was preparing for the EVA — namely station commander Mike Fincke and flight engineer Zena Cardman — who may have been unable or unwilling to do so themselves.

Within 24 hours of postponing the EVA, NASA held a press conference and announced Crew-11 would be coming home ahead of schedule as teams “monitor a medical concern with a crew member”. The timing here is particularly noteworthy; the fact that such a monumental decision was made so quickly would seem to indicate the issue was serious, and yet the crew ultimately didn’t return to Earth for another week.

Work Left Unfinished

While the reusable rockets and spacecraft of SpaceX have made crew changes on the ISS faster and cheaper than they were during the Shuttle era, we’re still not at the point where NASA can simply hail a Dragon like they’re calling for an orbital taxi. Sending up a new vehicle to pickup the ailing astronaut, while not impossible, would have been expensive and disruptive as one of the Dragon capsules in rotation would have had to be pulled from whatever mission it was assigned to.

So unfortunately, bringing one crew member home means everyone who rode up to the Station with them needs to leave as well. Given that each astronaut has a full schedule of experiments and maintenance tasks they are to work on while in orbit, one of them being out of commission represents a considerable hit to the Station’s operations. Losing all four of them at once is a big deal.

Granted, not everything the astronauts were scheduled to do is that critical. Tasks range form literal grade-school science projects performed as public outreach to long-term medical evaluations — some of the unfinished work will be important enough to get reassigned to another astronaut, while some tasks will likely be dropped altogether.

But the EVA that Crew-11 didn’t complete represents a fairly serious issue. The astronauts were set to do preparatory work on the outside of the Station to support the installation of upgraded roll-out solar panels during an EVA scheduled for the incoming Crew-12 to complete later on this year. It’s currently unclear if Crew-12 received the necessary training to complete this work, but even if they have, mission planners will now have to fit an unforeseen extra EVA into what’s already a packed schedule.

What Could Have Been

Having to bring the entirety of Crew-11 back because of what would appear to be a non-life-threatening medical situation with one individual not only represents a considerable logistical and monetary loss to the overall ISS program in the immediate sense, but will trigger a domino effect that delays future work. It was a difficult decision to make, but what if it didn’t have to be that way?

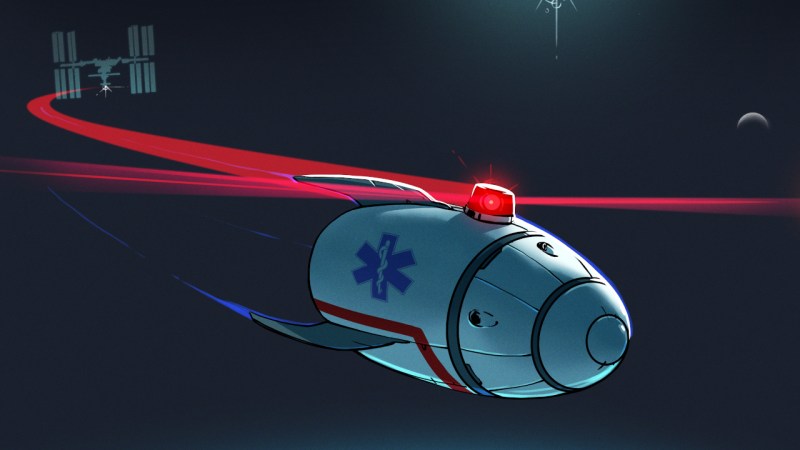

In other timeline, the ISS would have featured a dedicated “lifeboat” known as the Crew Return Vehicle (CRV). A sick or injured crew member could use the CRV to return to Earth, leaving the spacecraft they arrived in available for the remaining crew members. Such a capability was always intended to be part of the ISS design, with initial conceptual work for the CRV dating back to the early 1990s, back when the project was still called Space Station Freedom. Indeed, the idea that the ISS has been in continuous service since 2000 without such a failsafe in place is remarkable.

Unfortunately, despite a number of proposals for a CRV, none ever made it past the prototype stage. In practice, it’s a considerable engineering challenge. A space lifeboat needs to be cheap, since if everything goes according to plan, you’ll never actually use the thing. But at the same time, it must be reliable enough that it could remain attached to the Station for years and still be ready to go at a moment’s notice.

In practice, it was much easier to simply make sure there are never more crew members on the Station than there are seats in returning spacecraft. It does mean that there’s no backup ride to Earth in the event that one of the visiting vehicles suffers some sort of failure, but as we saw during the troubled test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 in 2024, even this issue can be resolved by modifications to the crew rotation schedule.

No Such Thing as Bad Data

Everything that happens aboard the International Space Station represents an opportunity to learn something new, and this is no different. When the dust settles, you can be sure NASA will commission a report to dives into every aspect of this event and tries to determine what the agency could have done better. While the ISS itself may not be around for much longer, the information can be applied to future commercial space stations or other long-duration missions.

Was ending the Crew-11 mission the right call? Will the loses and disruptions triggered by its early termination end up being substantial enough that NASA rethinks the CRV concept for future missions? There are many questions that will need answers before it’s all said and done, and we’re eager to see what lessons NASA takes away from today.

bad take. Crew-11 came back like 6 weeks earlier than planned on their 6-month mission – that’s not a catastrophe. If NASA had developed a lifeboat CRV they would still have to ensure enough return-seats for all remaining crew so it’s not at all certain that the rest of crew 11 would be able to stay. Then the CRV needs to be refurbished and re-launched… this is not the Gotcha! Nasa Idiots! that you think it is.

What is the per human hour cost of residency on the ISS amortized over the total cost of the ISS thus far including annual support costs like cargo flights, crew changes and ground support crews.

Grok:

The International Space Station (ISS) has incurred a cumulative total cost of approximately $250 billion as of early 2026, encompassing construction, assembly, operations, cargo resupply missions, crew rotations, and ground support across all international partners over its lifetime.

The station has been continuously occupied for 9,207 days (from November 2, 2000, to January 17, 2026), with a historical average crew size of roughly 5.06 people, yielding an estimated 46,571 cumulative person-days of human residency.

This equates to about 1,117,704 total human hours on the ISS.

Amortizing the $250 billion total cost over these human hours results in a per human hour cost of approximately $224,000.

What is the cost per science paper generated by the ISS mission considering its total cost thus far versus typical unmanned space probe missions?

Grok (excerpts):

ISS: $250 billion / ~4,400 total science paper produced from the ISS mission thus far = ~$56,818,181 per science paper.

Hubble Space Telescope: $10 billion (lifetime through mid-2020s; some estimates up to $15-16 billion) / 15,500+ total science papers thus far = ~$645,000 per science paper.

Book: The End of Astronauts: Why Robots are the Future of Exploration (2022)

Irrelevant, research and development value is not counted in papers.

Without intellectual/societal “currency units” defined by NASA, or other official agencies, by which at least a reasonable estimate of ROI can be made, this seems quite applicable–and relevant–until something better surfaces. Got something better? Let’s hear it.

Total citations of the papers?

Total citations of the papers citing the papers?

What’s the TLA (ETLA?) for the source of google’s page ranking algorithm?

Fanyo has a point, there are whole ‘sciences’ with many many papers that have produced nothing of value.

They also cite each other, so even that fails.

Google figured out how to find citation circle jerks, but never one as big as ‘sociology’.

“If NASA had developed a lifeboat CRV they would still have to ensure enough return-seats for all remaining crew”

If NASA had developed a lifeboat CRV they would still have to ensure enough return-seats for all remaining crew as is the situation today.

It’s not either-or.

Okay, so who of them is pregnant? ;)

(Just kidding! Another dude on the net asked this before.)

Winner! :-)

He doesn’t want to be named.

This is where my mind went, too. Unexpected or undetected pregnancy.

Astronauts are people, with all the inherent flaws. Just look at the “diaper-assassin”.

I would not doubt that some seek membership in the 200-Mile-High Club.

NASA is being tight-lipped because this would put some serious scrutiny on they “mixed-crew” promotional doctrine.

It all lines up.

It wouldn’t really, the only people who would care in a negative sense are the current administration.

Another case of TDS has been exposed.!

Really a lot of them recently in the comments section…

Couldn’t help but be reminded of the one-person emergency re-entry capsule, MOOSE https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MOOSE

But I’d guess even if they had a few of these stashed on the station they still would have opted for the “everyone on the bus, we’re going home” option, if only for the reliability.

Looks like a pretty wild ride. As close to spacediving as it gets (those high-altitude balloons don’t count, they have no velocity toward the horizon)

I like the idea of something a bit less backpacky than MOOSE http://www.astronautix.com/m/moose.html but not much. A Nice hard lenticular ablative heatshield being the largest difference, automated manuvering and it can still retain the solid rocket deorbit engine, maybe an entry door rather than spacesuit vacuum entry, and some way to ensure balance. Probably smething that can be attached behind a CSM(though there are safety issues with that too) about the size of a king size bed and maybe 100kg. Replace the cold gas manuvering tanks, solid rocket, and probably oxygen candle and CO2 scrubber every few years. Really these should be hanging all over the space station like individual lifeboats, open emergency hatch, enter, close door(seals space station, maybe even epoxys the hatch shut), fire detach squibs or gas, system determines orientation, manuvers, waits to be over friendly territory if desired, fires deorbit rocket, re-enter, deploys parachute and activates EPIRB. You could upgrade the thing for non-worst-case scenarios like our sick astronaut and maybe a nicer parasail vs conical most reliable parachutes. There is a case to be made for including a Fulton Skyhook system to avoid dangerous landing though that involves reviving substantial rescue aircraft infrastructure.

Adding in-atmosphere glide capability for a single occupant wouldn’t be incredibly difficult.

IMHO, with all the negative (mass-media) flak regularly hurled at NASA, I admire their ability to make do with the bare minimum engineers (as opposed to administrators that are more than plenty) and still deliver amazing results.

As far as NASA budget review goes, they are one of the lowest-paid entities comparably-speaking delivering outstanding results (speaking of the computer I am writing this reply on – we HAVE to thank NASA for that). We have more than plenty government agencies existing for no particular purpose other than, and I actually find it amazing that they are still delivering results they were asked to deliver.

I agree with your general sentiment that NASA is pretty cheap and a good return on investment, but NASA hasn’t contributed significantly to the development of computers.

NASA hasn’t significantly contributed to the development of computers?!?!!?

Just their aerodynamic simulations have driven large scale computing’s boundaries for the past 60+ years, nonetheless contributions to networking, graphics, algorithms. Take 5 seconds and ask about NASA on ChatGPT.

Yes, they have, and civil engineering on those computers, and the entirety of GIS, and all of the software it’s based on. It seems your understanding of their impact is very shallow, look into it.

Why isn’t the emergency return just an extra dragon capsule (or whatever they’re using at each point in time)? They’re proved to be reliable, and just having one extra docked would mean they’d have a spare. And rather than leave it unused for 20 years and hope it works, when people leave they just always ride the oldest one down, so all it means is each capsule is docked for a bit longer than currently.

I would guess that’s because the only “extra” dragon capsules they have would be configured for cargo. I have the idea that when a crew comes up, they leave on that same capsule…so to get an extra one, we’d have to send one without a crew. Which they do, but they don’t install seats in that one so it comes home empty / filled with garbage. I have no idea what it’d take to convert a cargo capsule to a crewed one in orbit.

Hm. That’s a good point, though I’m not sure if I’d trust a fancy, overengineered, macho SpaceY capsule over an USSR era Sojut capsule.

I somehow have more faith in them “rust buckets” than US products, which are more “show” than substance.

The Soyuz/Sojus were primitive, sure, but rock-solid.

Comparable to old Apollo capsules, but they stood the test of time.

Same goes for Progress freigthers, I guess, which are about as old.

Decay and damage from micro meteroites are another critical point, though.

I don’t know how these emergency capsules are “stored”.

If they are kept pressurized or not, for example.

Without oxygen, the absence of corrosion might not have aged an capsule so much.

I forgot to explain: What makes me think that way is the first showcase of such a modern US capsule that I saw.

It had lots of big TFT touch screens with sci-fi graphics just for “show”.

See “Figure 10” on this site, for example: https://tinyurl.com/mwtwtte

Because I think that in a real emergency, “real”, physical controls are a life saver.

Something you can feel through the gloves of a spacesuit, something less “digital”.

Just like with the old capsules. Sure, somemight say that the new ones might have a traditional backup system, too,

but how much control does it provide?

Is it as reliable orflexible as the real thing? I’m sceptical.

Why do you think the screens in the Crew Dragon are for show but not the screens, dials, and indicators in the Soyuz?

In an emergency none of the controls in either Soyuz or the Crew Dragon make the smallest bit of difference.

Hm. Not sure how to put it. It somehow reminds me of same situation as with avionics, I guess.

US had jets full of buggy hi-tec and solid-state technology early on,

while USSR had precise electro-mechanical solutions, miniature radio tubes etc.

The latter was more robust, could withstand EMPs etc.

Same goes for civil airplanes, I think. Some old Antonov plane still flies to this day, for example.

All in all, the US tech seems to be always (ok, often) sort of about demonstrating superiority, rather than being rational and longlived.

It has to be “state-of-the-art” no matter what.

(Reminds me of that 1960s interview with Wernher von Braun,

in which an interviewer talked about the US being superior because of having NTSC color TV or something. Sigh.)

But the real point is that the modern capsules are clearly show-offs, that the company is needy for good PR and success. And quickly.

The modern “space suits” were more like space pajamas than actual space suits.

They were useless without a pressurized cockpit. It’s just show, everything is so dramatized.

That’s not how serious space agencies used to be represented, I think.

Hm. I guess I’m just a relic of 20th century, such thinking nolonger is in fashion.

Hm. Or let’s put it this way: What’s more reliable/longlived, a venderable C64 with a simple green monitor and an analog VHF transistor radio (transceiver)

or some modern counterfeit smartphone made somewhere in China bundled with a fancy StarLinc subscription?

Personally, I’d go for the C64 and the analog radio,

which have stood the test of time and which can be fixed or bypassed (lots of trouble-shooting guides on-line).

The old technology also is more radiation resistant than a super-modern nanometer chip technology.

After decades in space without servicing, the more simple technology is more likely to still function, I think.

By comparison, the flash cells used in eMMC, SSD etc might be corrupted, but not so much late 20th century era technology

or physical controls directly wired to their own hardware.

Also, the systems used to be rather modular back in time.

There was no TCP/IP communication link between the embedded PCs running the touchscreens and the capsule’s control system(s).

There was nothing that could block the whole thing, in short. No blue screens, no viruses.

Soyuz vs modern capsule design is akin to running DOS vs Windows 11, maybe.

In an emergency, I’d rather trust plain, primitive DOS without any backgrouund tasks (a bit extreme comparison I must admit; Soyuz hardware changed over the decades, too).

I forgot to add: I’m thinking of the space capsule as a life boat here, one that might be left docked for years.

I’m not saying modern technology is a no-go or something.

Just that I’d have more faith in a less automatic, less overengineered technology when it matters (no AI, Windows or *nix etc).

Something were people still can make manual corrections, if it’s needed.

And especially space exploration always was such a field, I think.

More than often, humans had to correct errors here.

PS: To my defense, to give an idea what kind of older technology I was thinking of, for example:

https://hackaday.com/2023/01/23/inside-globus-a-soviet-era-analog-space-computer/

https://hackaday.com/2021/03/08/a-soyuz-space-clock-replica/

Older capsules had such or other modular systems that worked individually.

The globe even was installed in later capsule generations as a backup, as well,

when more recent computer systems were installed.

By comparison, the the aforementioned modern cockpit of with the touch TFTs reminds me more of a late 2000s LAN party than a space craft.

But I’m just a layman, of course. I never flew to space.

You are comparing very different things. Not that I am hoping Soyuz here, but the controls are there, none of it is for show. The dragon displays aren’t either, but lack functionality.

the pic really reminds me of a tesla car, probably where musk got the idea from.

Spend a not so small fortune supporting the station and then something ?reasonably critical? requiring evac and we have not a clue what is actually going on.

Sigh, still money well spent….

I’m actually a little irritated at the whole “concern for medical privacy” thing. IIRC we’ve seen this a few times before, and it’s always struck me as being misplaced.

I get that astronauts are individual human beings and as such are entitled to have their personal secrets. If I were an astronaut I would want it this way.

Yet they are also government employees, on a government mission, operating a government vessel, one that invests literally billions of dollars of public money on their individual status at any time.

At some point, the people paying for this – again, to the tune of literally billions of dollars – have a right to know what’s going on.

Does Bob your neighbor have an unfortunate malady that’s threatening his job performance? Here on Earth that’s none of your damn business.

Does Bob the government employee entrusted with billions of dollars of public equipment in an extremely unforgiving environment where literal lives are at stake all day long have an unfortunate malady that’s threatening his job performance?

That’s a question that more people than just Bob have a stake in.

The performance of these human factors matters to us, and that’s why we pay for multiple teams of experts on earth that are doing things like training, monitoring, treating, and even redesigning systems around discovered human frailty. We would be throwing away our money if we didn’t have the staff to supervise and maintain and improve our orbiting human resources.

But as to whether the juicy gossip ever gets back to us here…how does that matter? Not everyone at NASA is a saint but a lot of their staff is honestly interested in the mission and if there’s some sort of problem they’re running into that’s causing them problems, they will try to figure out how to control for that with their processes whether I’m there watching them or not. If citizen backseat driving was really essential to NASA’s success then they couldn’t stand a chance at the kind of missions they’ve been (mostly) successfully completing.

I do hope that if there’s a general lesson to learn, it will be published in some impersonalized / round-about way.

How do you figure anyone but their family and maybe their immediate actual employer has a “stake” in whether someone has cancer, heart disease, mental health issues or whatever? Yah, you’re the taxpayer. That doesn’t mean you own their privacy.

No offence, but apply this to someone you care about and think again.

It’s about failure analysis.

They need to figure out how the medical condition made it to orbit in the first place.

We don’t, they do.

Do we trust them to produce unbullshitted analysis?

What if this case resulted in ‘all women are at least 4 on the crazy scale’ and maximum crazy for an astronaut is 2?

If the rumors are true, the Ruskies will leak it.

I would say that in medical fashion it would be expected for one or two people to travel with a sick person depending on what the issue is to provide care in route so I don’t think a single crew return system would ever be a good idea.

Medical support in space is an intersting issue, and one that needs to be resolved before we can commit to something like a mars mission. People think that medical facilities on thne ISS are like the USS enterprise, but Kevin Fong once showed they are remarkable basic. The truth is like anything in space doing things that would of been routine on Earth, are very difficult in space. For example basic surgery such as a appendectomy has never been attempted and have complications such as allowing fluids to drain due to lack of gravity. So basiaclly apart from simple triage the best solution is to get them back to earth ASAP. This is achievable in the ISS, but not so much on a MArs mission

On ships, I once read, they had used slow scan tv to communicate with doctors on land or on other ships.

So they could do diagnose the patient and do assist from the distance.

It used the 7.2 (EU 50 Hz) or 8 (US 60Hz) second b/w format, originally. Nowadays often refered to as “Robot 8”, which most SSTV software supports.

(But Robot 8 is a bit different, actually. Original 8s SSTV was square aspect ratio and relied on sync pulses;

while Robot 8 used 4:3 format and added VIS code. Sync optional, free-running decode is possible.

In practice, both are very compatible to each other, though.)

Color Transmission was possible, too, if I understand correctly.

Using Wraase or Frame Sequential SSTV (one frame for R, G, B). Maybe using Robot 36c, too.

The nice thing is that it works on any voice channel of 3 KHz bandwidth.

More information, in German (what else 😉).:

https://seefunknetz.de/sstv.htm

Luckily, the ISS already has the equipment on board (just like Mir had).

The amateur radio station has SSTV over VHF!

The difference is, though, that the ships at sea back then had used real, professional TV video cameras with optical zoom. Not an pocket camcorder.

So even in low-resolution, the image was recognizable.

And in Antarctica, it doesn’t solve the problem of a medical condition they are unable to handle.

IIRC a person did a self appendectomy in Antarctica once.

All I can think of is what kind of insurance coverage they have that would pay for that kind of ambulance ride.

Why, when you are already paying for the vehicle?

Imagine being confined in the ISS with a dead body onboard…

I Hope there is no alien on board…

Frankly I’m appauled at the cheap skate approach being applied to space program. My country doesn’t have one but we contribute more then our fair share in both money and pieces, parts, and sensors than any other country other than maybe Japan. In addition, though not wildly known but not secret as I found out through the media and economic data, we even make sensors for the US NRO (the even more non-existent agency than the NSA. The spy satellites!

Why are we overcrowding LEO and not parking building materials, modular nuclear reactors, and everything we need for Moon and Mars bases in GEO or a parking orbit.

We’re shooting off tons of material but nothing of use for permanent moon bases building a large cargo station has enough space and ion thrust capability to make direct runs between planets? Don’t tell me that too so each one being five megawatts so the redundant couldn’t or does it have the power for huge ion trust engines to move it directly to Mars I’m back without orbital gravitational slingshots?

“Why are we overcrowding LEO and not parking building materials, modular nuclear reactors, and everything we need for Moon and Mars bases in GEO or a parking orbit.”

Probably because the geopolitical state of Earth is such that it’s too much like leaving your wallet on the sidewalk.

Play some GD KSP and learn something.

You’ll want the realism overhaul mods, so you can deal with radiation hazards.

It might save you future embarrassment.