We miss the slide rule. It isn’t so much that we liked getting an inexact answer using a physical moving object. But to successfully use a slide rule, you need to be able to roughly estimate the order of magnitude of your result. The slide rule’s computation of 2.2 divided by 8 is the same as it is for 22/8 or 220/0.08. You have to interpret the answer based on your sense of where the true answer lies. If you’ve ever had some kid at a fast food place enter the wrong numbers into a register and then hand you a ridiculous amount of change, you know what we mean.

Recent press reports highlighted a paper from Nvidia that claimed a data center consuming a gigawatt of power could require half a million tons of copper. If you aren’t an expert on datacenter power distribution and copper, you could take that number at face value. But as [Adam Button] reports, you should probably be suspicious of this number. It is almost certainly a typo. We wouldn’t be surprised if you click on the link and find it fixed, but it caused a big news splash before anyone noticed.

Thought Process

Best estimates of the total copper on the entire planet are about 6.3 billion metric tons. We’ve actually only found a fraction of that and mined even less. Of the 700 million metric tons of copper we actually have in circulation, there is a demand for about 28 million tons a year (some of which is met with recycling, so even less new copper is produced annually).

Simple math tells us that a single data center could, in a year, consume 1.7% of the global copper output. While that could be true, it seems suspicious on its face.

Digging further in, you’ll find the paper mentions 200kg per megawatt. So a gigawatt should be 200,000kg, which is, actually, only 200 metric tons. That’s a far cry from 500,000 tons. We suspect they were rounding up from the 440,000 pounds in 200 metric tons to “up to a half a million pounds,” and then flipped pounds to tons.

Glass Houses

We get it. We are infamous for making typos. It is inevitable with any sort of writing at scale and on a tight schedule. After all, the Lincoln Memorial has a typo set in stone, and Webster’s dictionary misprinted an editor’s note that “D or d” could stand for density, and coined a new word: dord.

So we aren’t here to shame Nvidia. People in glass houses, and all that. But it is amazing that so much of the press took the numbers without any critical thinking about whether they made sense.

Innumeracy

We’ve noticed many people glaze over numbers and take them at face value. The same goes for charts. We once saw a chart that was basically a straight line except for one point, which was way out of line. No one bothered to ask for a long time. Finally, someone spoke up and asked. Turns out it was a major issue, but no one wanted to be the one to ask “the dumb question.”

You don’t have to look far to find examples of innumeracy: a phrase coined by [Douglas Hofstadter] and made famous by [John Allen Paulos]. One of our favorites is when a hamburger chain rolled out a “1/3 pound hamburger,” which flopped because customers thought that since three is less than four, they were getting more meat with a “1/4 pound hamburger” at the competitor’s restaurant.

This is all part of the same issue. If you are an electronics or computer person, you probably have a good command of math. You may just not realize how much better your math is than the average person’s.

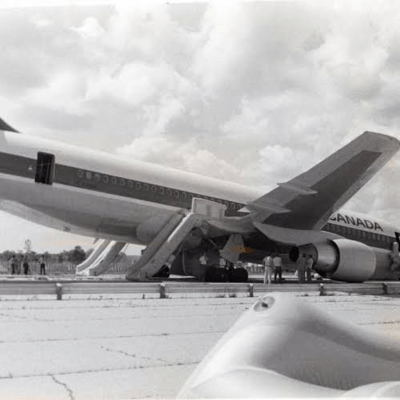

Gimli Glider

Even so, people who should know better still make mistakes with units and scale. NASA has had at least one famous case of unit issues losing an unmanned probe. In another famous incident, an Air Canada flight ran out of fuel in 1983. Why?

The plane’s fuel sensors were inoperative, so the ground crew manually checked the fuel load with a dipstick. The dipstick read in centimeters. The navigation computer expected fuel to be in kg. Unfortunately, the fuel’s datasheet posted density in pounds/liter. This incorrect conversion happened twice.

Unsurprisingly, the plane was out of fuel and had to glide to an emergency landing on a racetrack that had once been a Royal Canadian Air Force training base. Luckily, Captain Pearson was an experienced glider pilot. With reduced control and few instruments, the Captain brought the 767 down as if it were a huge glider with 61 people onboard. Although the landing gear collapsed and caused some damage, no one on the plane or the ground were seriously hurt.

What’s the Answer?

Sadly, math answers are much easier to get than social answers. Kids routinely complain that they’ll never need math once they leave school. (OK, not kids like we were, but normal kids.) But we all know that is simply not true. Even if your job doesn’t directly involve math, understanding your own finances, making decisions about purchases, or even evaluating political positions often requires that you can see through math nonsense, both intentional and unintentional.

[Antoine de Saint-Exupéry] was a French author, and his 1948 book Citadelle has an interesting passage that may hold part of the answer. If you translate the French directly, it is a bit wordy, but the quote is commonly paraphrased: “If you want to build a ship, don’t herd people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

We learned math because we understood it was the key to building radios, or rockets, or computer games, or whatever it was that you longed to build. We need to teach kids math in a way that makes them anxious to learn the math that will enable their dreams.

How do we do that? We don’t know. Great teachers help. Inspiring technology like moon landings helps. What do you think? Tell us in the comments. Now with 285% more comment goodness. Honest.

We still think slide rules made you better at math. Just like not having GPS made you better at navigation.

When I started my engineering degree in 1980, slide rules were already a curiosity. And curious I was. I eventually got my mitts on one and played with it. Understanding the fundamental logarithmic nature of it not only made me better at math, but also made me want to know more math.

And how have I never before encountered that quote from Mr. Petit Prince?

It’s amazing that this is still amazing to anyone who has spent multiple decades interacting with people on at least a semi-daily basis, though one of the common biases people have is the polite assumption that other people understand the conversation you’re having.

What’s interesting is that parts of the problem are not as simple as “innumeracy”. For example, if you ask which is larger, 1/3 or 1/4, what you’re really doing in words is asking “Which is larger, a third or a quarter?” First you have to parse the words out to mean fractional numbers. If the person is not primed for a math quiz and you spring the question on them, they may simply trip over it and answer nonsense. It’s like the trick of suddenly saying “The idiot says what?”. Ha ha, gotcha. Fast thinking vs. slow thinking mode. Your brain gets a cache miss and has to wait for RAM.

When people see an expression like “a quarter pounder”, that’s an arbitrary label. One doesn’t usually mind what it actually means. It’s a hamburger. If the usual choice is between a Big Mac and a Quarter Pounder, those words don’t mean numbers. It isn’t about math.

If you were asking the question as “Which is larger, a third or a fourth?”, the answer might be different. Now the brain isn’t instantly jumping to food, or the physical sizes of coins.

On a related note, people are generally not so much rational thinkers as they are associative and heuristic thinkers. That is the default mode. If that fails, then comes analytical thinking.

“Fast thinking vs. slow thinking mode. Your brain gets a cache miss and has to wait for RAM.”

LOL

One interesting thing I’ve learned from my travels is that different cultures intrinsically think and talk about math in different ways. I saw this while working in China.

From what I could gather, as someone who does not speak Chinese, the language has a subtly different way of dealing with numbers, in a way that simplifies the mental gymnastics involved.

There, the language for this question would not be “which is bigger one third or one quarter?”, it would more literally translate into “which is bigger, one out of three parts or one out of four parts?”

Likewise, the number 1592 would not be spoken as “fifteen-ninety-two”, it would be spoken much more explicitly as “one thousand, five hundred, nine tens, and two”.

It’s subtle, but it seems to me that it embodies more of the actual meaning of numbers, and less of then as logical tokens.

Depends on context: if that’s a phone extension or a street address it’s going to be said “one, five, nine, two” and of course the Chinese have two words for two. Ah the mysterious east.

That’s American English, not English.

As a Brit, I would at least say fifteen hundred and ninety two (if I’m feeling lazy). More usually, I would say one thousand five hundred and ninety two. I would never say fifteen ninety two, even after 6 years in the States.

There are many languages that don’t say “eleven”, they say an equivalent of “first of the next decade”, or when they say “a third”, they say “one part of three”. They are much more explicit, because they are agglutinative languages – they form words out of sub-parts with distinct meaning rather than having a separate label per idea (analytic languages).

What that means, each word almost explains itself. “Eleven” does not explain itself, you have to know what it means, whereas the Estonian “üksteist” (one + of the second) does.

Though for some historical reason, the counting words after the second decade usually continue in the form of “twenty one, twenty two…”

English retains the same feature, with “-teen” denoting “ten”, so thirteen is “three-ten”, but this is inconsistent. Teen has become to mean a number between 13-19 in particular, while the Estonian “-teist” is a general adjective, such as “poolteist” for one and a half (half + of the second).

The context defines what the “of the second” means – it’s generally adding the base unit, whether that’s 1 or 10.

Actually, it’s not. It literally means “4 oz. hamburger patty net weight before cooking”.

If they advertise their 3 oz. net weight before cooking hamburger as a quarter pounder, someone is going to sue them over it.

Yes, that is the literal meaning, but not what I meant with that.

It’s a label that refers to a particular thing, such as a particular burger available in a restaurant. We don’t, or at least many don’t, think of it in terms of the actual weight but in terms of the hamburger. We don’t eat a “hamburger with a 4 oz. patty”, we eat a Quarter Pounder. For all we care, it could be named “Royale with Cheese”.

The fact that someone might sue over mislabeling if the patty was actually 3 oz. is not relevant to the point.

BTW. the quarter pounder is actually a four and a quarter oz. patty. They changed it, possibly because somebody sued over the ambiguity.

Regarding a quarter pounder….the half gallon tubs of ice cream have been 3 pints for decades now but they’re still half gallons. To differentiate from the other two sizes, pint and budget bucket.

The street smart person doesn’t look at the name, they look at the burger they’re served.

The case with the 1/3 vs. 1/4 pound burger may well have been people comparing burgers to burgers and concluding that the Quarter Pounder is actually bigger due to what else they put in between the buns, while the marketing people put the blame on people being dumb to cover their own asses. After all, reality is what gets reported to management.

So how much copper would a big datacenter require? I don’t even know where to begin. Are we talking 3.3, 5, 12 volts where currents are high (per watt), or 220 volts and higher where currents would be much lower? Are you including distribution lines, transformers, and generators to get the power to the data center? What percentage of those lines would actually be aluminum instead? This would take a lot of fuzzy math to calculate.

Ok. How many blades of grass on a (US metaphor for global war football, not FIFA football) football field?

Yes, a lot of fuzzy math. but easy to be within an order of magnitude.

See Jon Bentley, Programming_Pearls, “The Back of the Envelope” (Column 7 in the second book edition. I don’t recall the CACM issue it was originally in)

An “order of magnitude” is sometimes defined as 0.3 to 3 times some arbitrary baseline. If the real answer and your answer fit within one order of magnitude of that baseline, your answer may still be 10x off in the worst case.

Usually much higher voltages – 480V and up for that kind of industrial setting.

Let’s reduce the power consumption of data centers by 500% by using beautiful green coal.

Well, there’s your perfect example of innumeracy right there.

People ‘longing for the sea’ suddenly become competent ship builders and sailors?

I don’t think so.

Teach generally competent people to ‘long for the sea’ perhaps, but that’s maybe 1 in 5.

Otherwise you’re just creating customers for GD cruise ships,

Perhaps future Darwin award winners.

The fact is the Innumerate are just stupid and/or lazy.

You can’t fix stupid and to ‘fix’ lazy you’ve got to do it early.

Idiocracy is a documentary.

You can fix how people are raised and taught so badly they think they’re inherently, congenitally, bad at things and they shouldn’t try. At least in theory.

There was a nice SF novel, I just forgot the name:

A guy wakes up in a locked room. He seems to have lost his long-term memory.

After some time he finds out that he measures household distances/weights in inches/feet/ounces, but technical ones in ISO. He is also able to convert them on the fly, finding that he’s not using imperial but American Survey units.

His conclusions: I must have grown up in the U.S., and I’m a technician or scientist.

It would be so easy if we could just split at this line:

Use cultural units for household or daily measures, but please use ISO when going technical or international. Tell me about your chocolate bars in ounces, I can convert that. But stop asking for 15/32 inch drilled holes (unless it’s archery).

This message will self-destruct in 2345/13 kobo-Ticks.

The novel is Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir. Motion picture to be released in March!

The book was great. I hope they don’t hollyweird this movie up like they do everything else. I am really looking forward to it!

” stop asking for 15/32 inch drilled holes”

The issue isn’t ‘metric vs customary.’ It’s two different standards groups. It’s ISO vs SAE. “15/32 inch” holes are metric. They’re exactly 11.90625 mm. The spacing isn’t “nice and round” but it’s just a number. Tolerance rounds it out anyway.

There are plenty of mixed metric/customary standards out there. All the rack standards are mixed. All the card dimensions are metric, but the spacings are HP which are 0.2″ (plus, obviously, the whole 19 inch thing). Doesn’t cause an issue.

And the fact that we have two standards groups isn’t surprising considering what was going on in the early 20th century.

In the 1960s, the image of a high school nerd was a kid walking to class wearing his K&E slide rule in a leather scabbard hanging from his belt (u-mercari-images.mercdn.net/photos/m32208348541_1.jpg)

Hopefully, that kid grew up into an engineer in the 70’s, realized that a technology revolution was at hand, and bought a few hundred dollars of Microsoft stock at 14 cents.

Wouldn’t have been possible but he mos’def bought a bitchin’ HP calculator which went in a similar zippable scabbard.

Believe it or not, I was one of those nerds with a HP41C in a nice leather holster on a belt loop. When I walked into a room once, one guy (seriously) asked if I was carrying. Most people there/then kept them in their briefcases (kid you not).

My high school classmates didn’t have briefcases, don’t try to teach your grandmother what was on The Brady Bunch.

Yeah, not high school. Business meetings. And nobody knew about any Brady Bunch there. Not that far from Elon Musk’s high school though, actually, but he would have been a pre-teen then.

So in South Africa then. Unbelievable.

When I was a kid in the late 80’s, I was the odd ball. I not only carried – and used – a slide rule, my rule of choice was a CIRCULAR slide rule. I still have that to this day!

I’ve been on that runway; it’s still used for racing, but the runway has been destroyed such that it isn’t useful in an equivalent emergency.

I all too often see graphs in the news media and on the WWW with no explanation of what the numbers on the axes mean.

“We miss the slide rule.”

No. No we don’t. And we don’t miss the dictionary sized book of logarithms we used to have to carry with it. For that matter we don’t miss carrying other books either (usually ~30 lbs of them in my undergrad days) through the snow and ice.

Forget calculators, when I retired four decades later, my engineering students were carrying a linked laptop and a phone as well as classes that were sent to them rather than the reverse so the snow and ice (as well as their location) was irrelevant.

If it makes anyone feel any better, they were still getting things wrong by orders of magnitude on occasion. It will be interesting to see if “AI” incorporates that as a human-necessary feature.

Why would you need a book of logarithms if you have a slide rule? Are you making that up?

Slide rules typically produce only one or two digits of accuracy. The books typically used 4-6 (or more) depending on the table. I suspect they also had more tables than a typical slide rule had scales. So you would use them for the same reason you would use a pencil/paper/slide rule instead of just rounding off to something easy enough to do mentally.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry he had quite a number of excellent books that should be read by high school kids in any country, really. Not merely for the joy of reading “foreign literature”, but for the joy of finding gems of thoughts the they can relate to, and there are plenty within.

BTW, might as well mention “Flight to Arras”. It may sound boring read, and at times it really is, but it is excellent book to persevere through, and doing so puts proper context to the only book really remembered in the US, “Le Petit Prince”, which is usually waved of as some kind of little kids’ fantasy book of no particular/good merit.

Also, “Wartime Writings”, however dry, is quite good read for another reason – it has excellent observations usually omitted from the official news/propaganda. This was before internet and everyone owning a cell phone one can take recordings with, so comes quite close to that.

Flight to Arras was my favourite, and I’ve been to the battlefields around Arras to see the ground over which he flew in 1940. Sadly he was lost on a reconnaissance mission in 1944 over France. His adage on longing for the immensity of the sea/air quoted in the article certainly applied to the Wright brothers and many of the early pioneers who used applied science and engineering to develop the first aircraft.

I think NASA found the answer after losing Mars Climate Orbiter: Mandate the use of SI units.

My understanding is that there have been no incidents since the loss of Mars Climate Orbiter regarding measurement units.

Innumeracy is so rampant, man. it’s hard to even be honest with people when you know that no matter what numbers you use it will be misunderstood.

Try giving a cashier a $20 dollar bill, a $1 bill, a quarter and three pennies when your bill is $16.28 and you want a single $5 bill in change. The confusion is it’s own entertainment.

oh man i learned not to do that more than a decade ago, when someone used the calculator on their personal iphone to resolve the crisis