The heat pump has become a common fixture in many parts of modern life. We now have reverse-cycle air conditioning, heat pump hot water systems, and even heat pump dryers. These home appliances have all been marketed as upgrades over simpler technologies from the past, and offer improved efficiency and performance for a somewhat-higher purchase price.

Heat pumps aren’t just for the home, though. They’re becoming an increasingly important part of major public works projects, as utility providers try to do ever more with ever less energy in an attempt to save the planet. These days, heat pumps are getting bigger, and will be doing ever grander things in years to come.

Magical Efficiency

The heat pump is a particularly attractive tool because it has a near-mystical property that virtually no other machine does. It is capable of delivering more heat energy than the amount of electricity fed into it, appearing to effectively have an efficiency greater than unity. We’re told that thermodynamic laws mean that we can never get more energy out than we put in. If you put 1 kW of electrical energy into a resistive heating element, which is near 100% efficient, you should get almost 1 kW of heat out of it, but never a hair more than that. But with a heat pump, you could get 1.5 kW, or even 2 kW for your humble 1 kW input. The trick is that the heat pump is not actually a magical device that can multiply energy out of nothing. Instead, the heat pump’s trick is that it’s not turning your 1 kW input into heat energy. It’s using 1 kW of energy to move heat from one place to another. If you’re running a heat pump-based HVAC system to cool your home, for example, it might use 2 kW of electricity to pump 3 to 4 kW of heat from your lounge room and dissipate it outdoors. Since the outdoors doesn’t change much in temperature when you pump out the heat from your home, you can keep doing this pretty much all day. You can even reverse the flow if your heat pump system allows it, instead pumping heat from the outdoors into your home. This works well until temperatures get so low that there isn’t enough heat left in the outdoors to appreciably warm your house up.

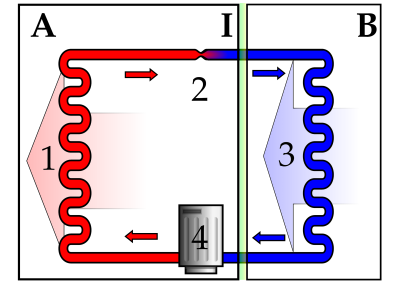

The heat pump achieves the feat of making heat go where we want it to go via the use of refrigerant. Specifically, refrigerant enters the compressor as a low pressure and low temperature vapor. It exits as a gas at high temperature and high pressure, and is then passed through a series of condenser coils. As it passes through, it releases heat to the surrounding environment and reduces in temperature, condensing into a liquid. From there, the liquid, still under high pressure, passes through an expansion valve, which rapidly lowers the pressure and drops the temperature further. The liquid is now cold, and passes through an evaporator coil where it picks up heat from the surroundings and turns back into a low-pressure, low-temperature vapor to start the cycle again as it heads back to the compressor. This system runs your fridge, your car’s air conditioner, and is used in so many other applications where it’s desirable to make something colder or hotter as efficiently as possible. You just choose which direction you want to pump the heat and design the system accordingly. Air conditioners and fridges pump heat out of a confined space, heaters and dryers pump it in, and so on. It’s heat pumps all the way down!

Bigger Applications

Thus far, you’ve probably used many a heat pump in your daily life, whether it be for heating, cooling, or drying clothes. However, there is a new push to build ever-larger heat pumps to work on the municipal scale, rather than simply serving individual households. The hope is to make utilities more energy efficient, and thus cheaper and greener in turn, by taking advantage of the efficiency gains offered by the magic of the heat pump.

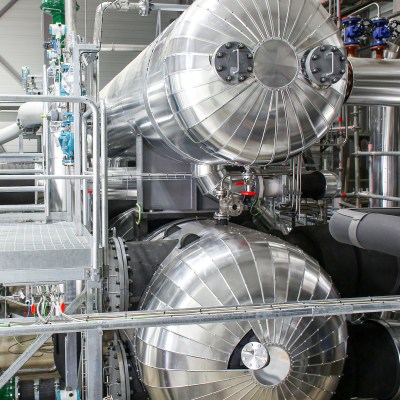

One such project is taking place just off the River Rhine in Germany. A pair of massive heat pump units are being constructed by MVV Energie, each with a capacity of 82.5 megawatts. They will deliver heat to a total of 40,000 homes via a district heating system, and will be constructed on the site of a former coal power plant. Each pump will effectively draw energy out of the massive watery heat battery that is the River Rhine, and use it to warm homes in the local area. Thankfully, the river’s capacity is large enough that drawing all that heat out of the river should only affect temperatures of the water by around 0.1 C.

The Rhine project builds upon a previous effort to install a large heat-pump heating system in Mannheim, in partnership with Siemens Energy. That installation draws 7 megawatts of electricity to supply 20 megawatts of heating to the local district heating grid. Installed in 2023, it supplies the heating needs of 3,500 local households.

A similar project is underway in Denmark, which will supply 177 megawatts of heat to homes in Aalborg. The installation of four 44 megawatt MAN Technology heat pumps will be hooked up to the existing district heating system, which is also supported by other sources including waste heat from a local cement factory. The benefit of using smaller individual units is that it allows some of the pumps to be shut down when heating demand is lower, as winter passes through autumn into summer.

What makes these projects special is their sheer scale. Rather than being measured in the kilowatt scale like home appliances, they’re measured in the many tens of megawatts, delivering heating to entire neighborhoods instead of single homes. As it turns out, heat pumps work just fine at large scales—you just need to build them out of bigger components. Bigger compressors, bigger expansion valves, and bigger condensors and evaporators—all of these combine to let you pump enormous amounts of heat from one place to another. As utilities around the world seek ever greater efficiency in new projects, heat pumps will likely grow larger and be deployed ever more widely, seeking to take advantage of the free heat on offer in the earth, water, and air around us. After all, there’s no point dumping energy into making heat when you can just move some that’s already there!

Puzzled by “near 100% efficient” for resistive heating. Is it really only “near”? I thought it was exactly 100%. The only way I can imagine for the energy to do non-heating work is inductive coupling. Like a forced-air electric furnace is gonna have a heating element inside a metal box / duct, and the 60Hz AC running through the element will have some interaction with the enclosure. But won’t that interaction just induce eddy currents that generate heat in the enclosure? Curious what other effects there could be…

And as for heat pumps becoming ineffective at low temperatures…it’s not really a question of having enough heat outside. The coldest winter’s air is still about 240K…just an enormous amount of heat still present. The trouble isn’t that the environment isn’t warm enough, but that it condenses all of the moisture out of the air and forms a layer of ice on top of the coils, isolating it from the environment. It does make me curious how cold the inside layer of that ice will become once it’s isolated…

The thing i always keep in mind is that as these things scale, the natural reservoir that you’re heating or cooling really does start to look shockingly finite..

“near 100%” because you lose a few percent of the electrical power between the location you generate it (or meter it) and the location you convert it to heat.

But it’s only ‘lost’ as heat -> as we’re looking for heat then it’s not lost at all, just perhaps not providing heat where it’s wanted.

the heating elements glow read hot while doing this right? so in addition to what was said above that conversion to visible light is a (small) energy loss if we’re being pedantic.

The visible light is absorbed and converted to heat

It is not 100%. Some is converted into magnetic flux.

The produced magnetic field consumes none of the electrical current unless that field is doing work. Even with a purpose-built electromagnet, the current draw is entirely from the resistance of the coil except when the field is moving something / something is moving through it.

True for DC fields. Not necessarily true with AC. If there is a loop with any cross-sectional area, it will act as a (spectacularly inefficient) antenna, radiating a miniscule amount of power away.

But none of the current is “consumed” in any case. All the current that enters the load also exits it. We are talking about power here, not current.

The field will do work by being converted into current in nearby conductive components…

About 2-6% in the usual case, up to 10-15% if you have to transmit longer distance.

For actual non-heat losses, there is the small amount of ULF radio energy that gets emitted by power lines.

A few?

Grid efficiency is circa 10% loss.

No comment.

You could also lose some through sound or light – for example an old style one bar heater also glows, so some of the energy will be lost to that.

But what happens to that light/sound? It hits a surface and get transformed in to heat.

Not if it goes out a window.

Even that won’t stop the heat pump from working. What does is the fact that the working fluid, such as R-22, boils at −40.7 °C so the heat pump stops working entirely when the ambient temperature reaches about 40 below zero, C or F. Other refrigerants have different boiling points, some higher, some lower. Propane goes down to -42 C.

The difference in temperature between the outside air and the boiling refrigerant directly determines the rate of heat flow into the system. It’s like Ohm’s law: temperature difference is the voltage that drives current through whatever resistance you have, which could be frosted coils or not. When the difference is small, very little heat gets in anyways and there’s little or nothing to pump, so the coefficient of performance approaches 1. At some point the heat leaking out through the tubing exceeds the amount of heat you can pump from the boiling refrigerant, so the efficiency of the system drops below 1. This typically happens when the outdoor temperature drops below -20…-25 C.

It becomes slightly above the boiling point of the refrigerant. Commonly around -40…-50 C.

Everything is an antenna, even a heating element, so at 50Hz/60Hz a minuscule amount of energy radiates away in a different part of the electromatic spectrum than the desired Infrared.

It’s not 100% because some of the power is lost in the heat generated elsewhere in the system, rather than where you intended to generate it.

Imagine a heat sink in a perfectly insulated vat of fluid with cables sticking out.

A resistive heating element itself is 100% efficient. But the cables connecting it to a power source act as a heat sink and also have resistive losses themselves.

In practice the vat and pipes also have losses. While that is not unique to resistive heating it does mean it can never reach 100% potential.

I would ignore AC losses since you can also use DC for resistive heating.

Love it. But what about the heat losses during the transport of the produced heat to the houses? Won’t we be trading one efficiency for multiple inefficiencies?

So you get a water temperature drop of 0.1K per 40k people. The river Rhine is home to at least 50 million people. That gives us a drop of 125 Kelvin if every home is heated by heat pumps. I really would like to see how that plays out. :evilgrin:

If the minimum water temperature in the Rhine averages 4.7°C in January, it would mean that the entire river would freeze over at the heating load of about 2 million people.

But fortunately, the latent heat capacity of freezing is 80 times greater, so what you could do is deliberately freeze the water into blocks and then release those blocks to float down to the sea.

It’s also a viable idea at home. If your landlord doesn’t let you install an air source heatpump, you can get a freezer and load it up with buckets of water from the tap. Then just keep throwing the ice blocks out the window…

Nice. I’d stand the refrigerator in the doorway, with the fridge open to the outside in winter, open to the inside in summer.

I realize you’re joking, but I’d just do a “swamp cooler”. You fill a bath tub with hot or cold water (depending on your temperature goal) and blow a fan over it. When the water gets near room temperature, drain it and repeat.

I tried this. It doesn’t work.

A top-floor walkup apartment I lived in had hydronic heating (hot water baseboard radiators) throughout the whole building. The boiler failed one very cold night and it got cold, fast. Oddly, the domestic hot water supply was a separate system…

I tried filling the bathtub with hot water and run a fan to exchange air out to the rest of the apartment. Nada. No way could I get enough heat out.

I tried running the shower instead, thinking continuous hot water and lots of surface area would do the trick. That just made it cold and damp with water condensing on the walls, and didn’t raise the temperature much.

So I turned on the electric oven to 200F and left the door open. That and the two front burners on medium kept the place tolerable for the 12 hours or so it took to repair the heating plant. I estimate I was burning 3 kW.

Yep. The problem is that evaporating the water cools it down, and then it condenses on the windows and the cold walls, and that condensation releases the stored heat into the walls instead of heating up the room air.

The trick is to put the hot water in buckets with lids on, and distribute the buckets around the house. One 10 liter bucket containing 55 C water off the tap contains about 1.7 MJ of heat down to 15 C, and with the water cooling down over the next couple hours, it averages about 250 Watts per bucket.

You still need about 12 of them to match the 3 kW from the electric hob, which means you might not have enough buckets available, but you can use doubled up trash bags instead, like big water balloons.

What (watt) is the CoP of a domestic fridge, I wonder? I suppose it’s experiment time, electricity meter and 10l of water in to be frozen.

What useful information is contained in the CoP, anyway? I’d rather want to know which fraction of the Carnot efficiency that thing archieves depending on lower and higher temperature, and power demand. The CoP distills a single number out of this set of multiple twodimensional graphs by applying more or less arbitrary assumptions of typical use cases, which may or may not reflect my use case, so it barely offers a first guess on what to choose or how to optimize.

Wait, are you suggesting that the math doesn’t check out for all this net zero nonsense?

Burn him, he’s a witch!!!

No, it’s just obvious nonsense. The Rhine is not flowing in an insulated pipe. If you cool it down in one location, it’s going to absorb more heat downstream, so you can cool it down again and again and again along its 1200 km without ever actually dropping the temperature by much.

Also, obviously, not everyone living in the vicinity of the Rhine will get heating from river heat pumps. Only a small minority will. They only really make sense for very densely populated areas where there isn’t sufficient space to install individual air source heat pumps, which will cover most of the heating needs.

It does heat up along the way, but it’s also a bit limited. I mean, it usually takes up to mid-summer before large bodies of water really start to warm up. It takes months, because geothermal heat from below is negligible, and the wind doesn’t carry in heat because any time it gets windy you get more evaporation, so the majority of heat has to come in from the sun.

Imagine for example that you have a 2 meter deep lake. The average yearly insolation around, let’s say Munich in southern Germany, is 2.98 kWh/m^2/day. Each square meter column of water therefore receives around 10 MJ of energy, and therefore would heat up by ~1.28 degrees C per average day.

Now suppose that 1x1x2 m column of water is moving down a river. Here we’re assuming the river is approximately two meters deep. It takes about two weeks for water to flow down the river Rhine, so it would be plausible that the water can pick up something like 18 degrees of heat by the time it flows to the sea. In fact, that’s how much we would expect the entire river to warm up by the time it reaches the sea, from the near-zero temperature of the glacial waters up the mountains.

If the temperature is reduced by people siphoning the heat out, and every 40k people reduce it by 0.1 degrees, then the amount of people you can sustain without starting to freeze the water is about 7.2 million – accounting for the heat it might pick up along the way to the sea.

Of course it would be much lower in the winter when there isn’t much sunlight available. In this case we used Munich, which gets down to 0.79 kWh/m^2/day in the winter, which would correspond to 1.9 million people, which matches my earlier estimate of 2 million based on the average minimum water temperature during the heating season.

Such as Köln (~1 million), Düsseldorf (~0.6 million), Dortmund (~0.6 million), Essen….

There are plenty of large cities along the Rhine that could tap into the river for their district heating systems, and all combined would easily exceed the available heat in the river.

There’s plenty of heat left. It’s nowhere near absolute zero. It’s just your heat pump that gets less and less effective with increasing temperature difference between outside and inside. Eventually it’s going to get so bad that the heat pump starts leaking heat backwards and heating the outdoors with the heat from your house.

Correct, heat pumps also have an absolute limit on the maximin lift that can manage in practice. People with a navie understanding of them often present them as magical heat movers that have no signifigant problems whereas the truth is that they are limited in use outside of a fairly narrow range. If heat pumps were as useful as some think then we could also use them for industrial heat and making turbines more efficient. Spend an hour or two talking to Grok about the physics and real world engineering behind heat pumps and related technologies and their true limits become very clear.

More critical to the lower limit of an air-sourced heatpump is the efficiency of thermal transfer between the coils and the outside air at lower temperatures. In normal operation, the fan sucks air through the radiator vanes that the coils are embedded in, which provides plenty of opportunity to transfer energy between large volumes of air and the working fluid. However, when the temperature drops, the moisture in the air starts to freeze on the vanes, which blocks the airflow between them. Yes, there’s still thermal transfer between the working fluid and the air, but it’s now severely reduced because the air the fan is moving is no longer traveling quickly through the vanes and past the coil directly, but mostly just lingering in the vicinity of the block of ice that happens to contain the coil.

This is why ground- or water-sourced heatpumps can be far more efficient in otherwise extreme environments, without needing such fancy refrigerants: they can rely on a very specific and very narrow temperature range that they need to interface with, and are immune to the vagaries of things like moisture freezing on the coils and curtailing the thermal transfer.

How are they delivering the heat? Is this via steam or hot water loops, or does it send out refrigerant gas to be compressed and condensed at people’s homes and liquid refrigerant in the summer?

The linked article provides the answer.

Ah, I see it’s circulating hot water. Some European heat pump projects have been using heat pumps to make steam, which isn’t a very efficient way to use them.

So you aren’t allowed to say sh1t, but you are allowed to say Siemens? What the fudge?

Can we say “Wayne-Kerr”?

Cities should be mandating that data-centres (AI boo hiss) capture the heat from their equipment and feed it into municipal heating systems.

When it’s to hot to use the heat for heating, pump the heat into the ground where it can be recovered in the winter with ground source heating.

But folks also want their homes to be far away from industrial buildings–including data centers.

https://www.itv.com/news/granada/2025-11-20/no-breach-of-planning-control-wigan-council-refuse-stop-notice-on-warehouses

Enjoy.

Yeah but the problem is they are building them where energy is cheap. Like desert regions.

USA centric based on 2500 SqFt home (annual):

national average for a standard home of this size typically falls within the 110–125 GJ range (total energy consumption – EIA figure.)

The fission of 0.001 grams of U235 produces 82 GigaJoules as heat.

(And a lot of nasty daughter products that have a recycling cost.)

Somewhere, the electricity to run the heat-pumps must be reconciled in an effective energy policy as presently pure-green electricity will not provide for the world need.

Dont say the quiet bit out loud.

Presently, heat pumps aren’t installed everywhere, either. While you install them, you also install renewable electricity generation. So, you do have the renewable electricity when you actually need it.

Also, heat pumps running purely on electricity from gas power plants only use roughly half as much natural gas as burning it in a gas boiler (depends on you location, of course), so no need to wait for all-green electricity in order to reduce CO2 emissions with heat pumps, actually.

“as winter passes through autumn into summer.”

Uhhh…….say what, now?

Ooops. Left the heat pump running backwards.

Backwards O Time in Thy Flight!

“Since the outdoors doesn’t change much in temperature when you pump out the heat from your home, you can keep doing this pretty much all day.”

That’s pretty much true out in the country, it definitely starts to be a problem in large crammed cities…

Fortunately, all that heat leaks back out of the houses just as quickly as you’re pumping it in.

If it’s just as quickly, you skipped over the proper insulation part of heat pump installation.

The insulation does not affect that part of the equation: in steady state it is always in=out. Insulation determines how much power you need to keep a given temperature difference between inside and outside with dT/dt=0

“utility providers try to do ever more with ever less energy in an attempt to save the planet.”

The cynic in me read that as “… in an attempt to make more money.”

I worked a diary farm that used a pair of Mitsubishi heat pumps to pull heat off the raw milk and dumping it into a hot water tank. Even milking just once a day in the winter kept their 500 gallon water tank humming along at around 90 degrees. The whole milking parlor and barn had hot water washdown. The cool part was that they captured all of the runoff and sold it for irrigation water with sub 3% solids.

It got me to thinking about house designs where waste heat from refrigerator and freezer units could be pumped to a hot water tank for the whole house to use. Might take a few years to off set the costs of extra plumbing but I think it would pencil out in the end.

I think the cost might be higher than you’d think, but a central hydronic balance-of-heat system might be very interesting. The refrigerator, laundry, PCs, power inverter systems. You could do a lot of work with low-grade waste heat if you could get the cost of the heat pumps down.