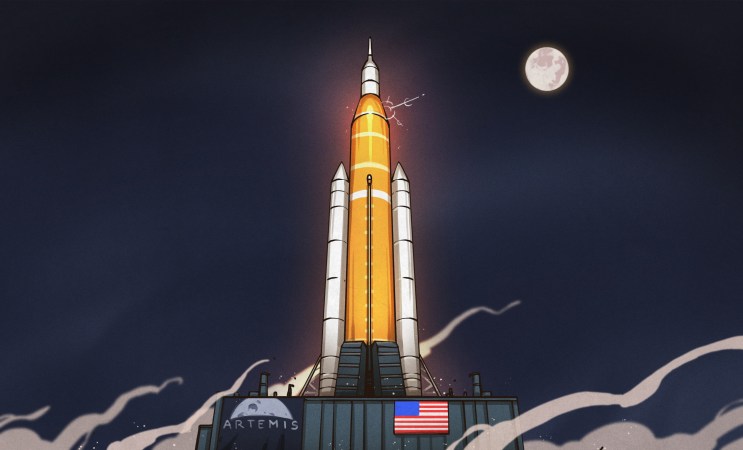

In their recent announcement, NASA has made official what pretty much anyone following the Artemis lunar program could have told you years ago — humans won’t be landing on the Moon in 2028.

It was always an ambitious timeline, especially given the scope of the mission. It wouldn’t be enough to revisit the Moon in a spidery lander that could only hold two crew members and a few hundred kilograms of gear like in the 60s. This time, NASA wants to return to the lunar surface with hardware capable of setting up a sustained human presence. That means a new breed of lander that dwarfs anything the agency, or humanity for that matter, has ever tried to place on another celestial body.

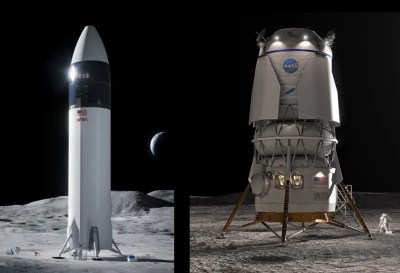

Unsurprisingly, developing such vehicles and making sure they’re safe for crewed missions takes time and requires extensive testing. The simple fact is that the landers, being built by SpaceX and Blue Origin, won’t be ready in time to support the original Artemis III landing in 2028. Additionally, development of the new lunar extravehicular activity (EVA) suits by Axiom Space has fallen behind schedule. So even if one of the landers would have been ready to fly in 2028, the crew wouldn’t have the suits they need to actually leave the vehicle and work on the surface.

But while the Artemis spacecraft and EVA suits might be state of the art, NASA’s revised timeline for the program is taking a clear step back in time, hewing closer to the phased approach used during Apollo. This not only provides their various commercial partners with more time to work on their respective contributions, but critically, provides an opportunity to test them in space before committing to a crewed landing.

Continue reading “New Artemis Plan Returns To Apollo Playbook”