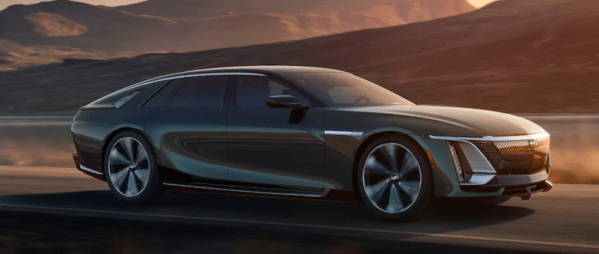

It can be amusing sometimes, to read an incredulous reaction from outside our community to something that would be bread-and-butter in most hackerspaces. Take the sorry saga of the Cadillac XLR tail light, as reported by Jalopnik. This car was a more-expensive Corvette with a bit of lard around its midriff, and could appear a tempting pick for a bit of inexpensive luxury rubber-burning were it not for the revelation that a replacement second-hand tail light for one of these roadsters can set you back as much as three grand. The trusty auto on the drive outside where this is being written cost around a tenth that sum, so what on earth is up? Is it because a Caddy carries some cachet, or is something else at play?

It appears that the problem lies in the light’s design. It’s an LED unit, with surface mount parts and a set of fragile internal PCBs that are coated in something that makes reworking them a challenge. On top of that, the unit is bonded together, and instead of being a traditional on-off tail light it’s a microprocessor-controlled device that gets its orders digitally. This is all too much for XLR owners and for the Jalopnik hacks, who castigate General Motors for woefully inadequate design and bemoan the lack of alternatives to the crazy-expensive lights, but can’t offer an alternative.

Reading about the problem from a hardware hacker perspective they are right to censure the motor manufacturer for an appalling product, but is there really nothing that can be done? Making off-the-shelf microcontroller boards light up LEDs is an elementary introduction project for our community, and having the same boards talk to a car’s computer via CAN is something of a done deal. Add in LED strips and 3D printing to create a new backing for the tail light lens, and instead of something impossibly futuristic, you’re doing nothing that couldn’t be found in hackerspaces five years ago.

So what’s to be learned from the Cadillac XLR tail light? First of all, there’s scope for an enterprising hacker to make a killing on a repair kit for owners faced with a three grand bill. Then, there’s another opportunity for us to be acquainted with the reality that the rest of the world hasn’t quite caught up with repair culture as we might imagine. And finally there’s the hope that a badly designed automotive component might just be the hook by which the issue of designed-in obsolescence moves up the agenda in the public consciousness. After all, there will be other similar stories to come, and only bad publicity is likely to produce a change in behavior.

Of course, to get it really right you need a car that’s hackable in the first place. Or better still, one designed by and for hackers.

Thanks [str-alorman] for the tip.

Cadillac XLR header image:Rudolf Stricker [CC BY-SA 3.0].