For as long as small, hidden radio transmitters have existed, people have wanted a technology to detect them. One of the more effective ways to find hidden electronics is the nonlinear junction detector, which illuminates the area under investigation with high-frequency radio waves. Any P-N semiconductor junctions in the area will emit radio waves at harmonic frequencies of the original wave, due to their non-linear electronic response. If, however, you suspect that the electronics might be connected to a dangerous device, you’ll want a way to detect them from a distance. One solution is harmonic radar (also known as nonlinear radar), such as this phased-array system, which detects and localizes the harmonic response to a radio wave.

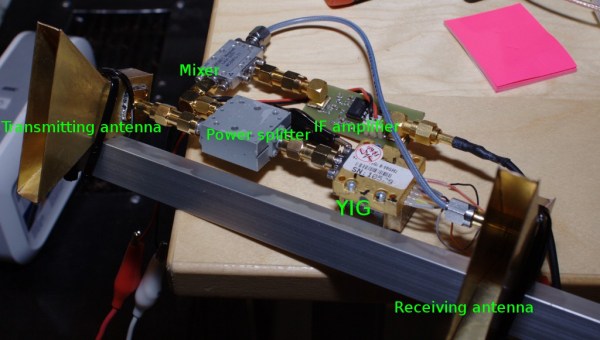

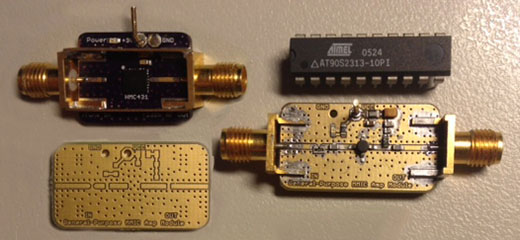

One basic problem is that semiconductor devices are very rarely connected to antennas optimized for the transmission of whatever harmonic you’re looking for, so the amount of electromagnetic radiation they emit is extremely low. To generate a detectable signal, a high-power transmitter and a very high-gain receiver are necessary. Since semiconductor junctions emit stronger lower harmonics, this system transmits in the 3-3.2 GHz range and only receives the 6-6.4 GHz second harmonic; to avoid false positives, the transmitter provides 28.8 decibels of self-generated harmonic suppression. To localize a stronger illumination signal to a particular point, both the transmit and receive channels use beam-steering antenna arrays.

In testing, the system was able to easily detect several cameras, an infrared sensor, a drone, a walkie-talkie, and a touch sensor, all while they were completely unpowered, at a range up to about ten meters. Concealing the devices in a desk drawer increased the ranging error, but only by about ten percent. Even in the worst-case scenario, when the system was detecting multiple devices in the same scene, the ranging error never got worse than about 0.7 meters, and the angular error was never worse than about one degree.

For a refresher on the principles of the technology, we’ve covered nonlinear junction detectors before. While the complexity of this system seems to put it beyond the reach of amateurs, we’ve seen some equally impressive homemade radar systems before.

The project featured in this post is

The project featured in this post is