Vending machines used to be a pretty simple affair: you put some coins in, and food or drink that in all likelihood isn’t fit for human consumption comes out. But like everything else today, they are becoming increasingly complex Internet connected devices. Forget fishing around for pocket change; the Coke machine at the mall more often than not has a credit card terminal and a 30 inch touch screen display to better facilitate dispensing cans of chilled sugar water. Of course, increased complexity almost always goes hand in hand with increased vulnerability.

So when [Matteo Pisani] recently came across a vending machine that offered users the ability to pay from an application on their phone, he immediately got to wondering if the system could be compromised. After all, how much thought would be put into the security of a machine that basically sells flavored water? The answer, perhaps not surprisingly, is very little.

So when [Matteo Pisani] recently came across a vending machine that offered users the ability to pay from an application on their phone, he immediately got to wondering if the system could be compromised. After all, how much thought would be put into the security of a machine that basically sells flavored water? The answer, perhaps not surprisingly, is very little.

The write-up [Matteo] has put together is an outstanding case study in hacking Android applications, from pulling the .apk package off the phone to decompiling it into its principal components with programs like apktool and jadx. He even shows how you can reassemble the package and get it suitable for reinstallation on your device after fiddling around with the source code. If you’ve ever wanted a crash course on taking a peek inside of Android programs, this is a great resource.

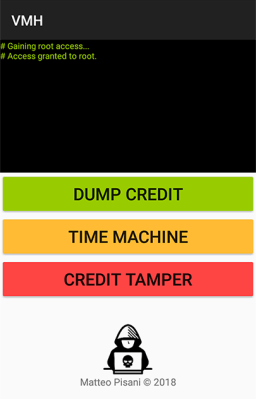

By snooping around in the source code, [Matteo] was able to discover not only the location of the encrypted database that serves as the “wallet” for the user, but the routine that generates the encryption key. To cut a long story short, the program simply uses the phone’s IMEI as the key to get into the database. With that in hand, he was able to get into the wallet and give himself a nice stack of “coins” for the next time he hit the vending machines. Given his new-found knowledge of how the system works, he even came up with a separate Android app that allows adding credit to the user’s account on a rooted device.

In the video after the break, [Matteo] demonstrates his program by buying a soda and then bumping his credit back up to buy another. He ends his write-up by saying that he has reported his findings to the company that manufacturers the vending machines, but no word on what (if any) changes they plan on making. At the end of the day, you have to wonder what the cost-befit analysis looks like for a full security overhaul when when you’re only selling sodas and bags of chips.

When he isn’t liberating carbonated beverages from their capitalistic prisons, he’s freeing peripherals from their arbitrary OS limitations. We’re starting to get a good idea about what makes this guy tick.