I’m excited to share the news that Elecia White will deliver a keynote talk at the Hackaday Remoticon in just a few short weeks. Get your free ticket now!

Elecia is well-known throughout the embedded engineering world. She literally wrote the book on it — or at least a book on it, one I have had in my bedside table for reference for years: O’Reilly’s Making Embedded Systems: Design Patterns for Great Software. She hosts the weekly Embedded podcast which has published 390 episodes thus far. And of course Elecia is a principal embedded software engineer at Logical Elegance, Inc working on large autonomous off-road vehicles and deep sea science platforms.

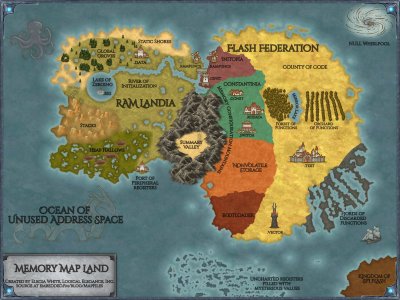

.map files, but how many of us have dared to really dive in?

Elecia will use a nifty metaphor for turning the wall of text and numbers into a true map of the code. That metaphor makes the topic approachable for everyone with at least a rudimentary knowledge of how embedded systems work, and even the grizzliest veteran will walk away with tips that help when optimizing for RAM usage and/or code space, updating firmware (with or without a bootloader), and debugging difficult crash bugs.

This autumn is a busy time for Elecia. She’s been hard at work turning her book into a ten-part massive open online course (MOOC). Over the years she’s been a strong supporter of Hackaday, more than once as a judge for the Hackaday prize (here’s her tell-all following the final round judging of the 2014 Prize). She even took Hackaday on a tour of Xerox Parc.

Final Talk Announcements This Week and Next!

The Call for Proposals closed a few days ago. So far we’ve made two announcements about the accepted talks and we’ll make two more, this Thursday and next. But there’s no reason to wait. With Elecia White, Jeremy Fielding, and Keith Thorne presenting keynotes, and some superb social activities soon to be unveiled, this is an event not to be missed!

Remoticon is free to all, just head over and grab a ticket! If you want something tangible to remember the weekend by you can grab one of the $25 tickets that scores you a shirt, but either option gets you all the info you need to be at every virtual minute of the conference.