The site is called Hackaday, and has been for 21 years. But it was only for maybe the first half-year that it was literally a hack a day. By the 2010s, we were putting out four or more per day, and in the later 20-teens, we settled into our current cadence of eight hacks per day, plus some original pieces over the top. That’s a lot of hacks per day! (But “Eight-to-Ten-Hacks-a-Day” just isn’t as catchy.)

With that many posts daily, we also tend to reach out to a broader array of interests. Quite simply, not every hack is necessarily going to be just exactly what you are looking for, but we wouldn’t be writing it up if we didn’t think that someone was looking for it. Maybe you don’t like CAN bus hacks, but you’re into biohacking, or retrocomputing. Our broad group of writers helps to make sure that we’ll get you covered sooner or later.

What’s still surprising to me, though, is that a couple of times per week, there is a hack that is actually relevant to a particular project that I’m currently working on. It’s one thing to learn something new every day, and I’d bet that I do, but it’s entirely another to learn something new and relevant.

What’s still surprising to me, though, is that a couple of times per week, there is a hack that is actually relevant to a particular project that I’m currently working on. It’s one thing to learn something new every day, and I’d bet that I do, but it’s entirely another to learn something new and relevant.

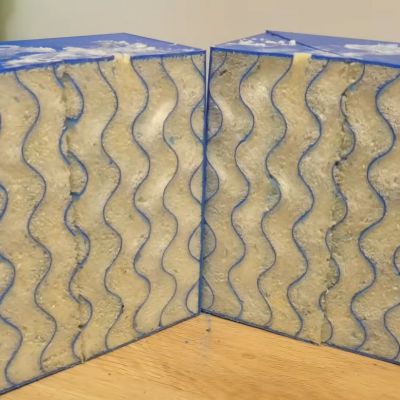

So I shouldn’t have been shocked when Tom and I were going over the week’s hacks on the podcast, and he picked an investigation of injecting spray foam into 3D prints. I liked that one too, but for me it was just “learn something new”. Tom has been working on an underwater ROV, and it perfectly scratched an itch that he has – how to keep the top of the vehicle more buoyant, while keeping the whole thing waterproof.

That kind of experience is why I’ve been reading Hackaday for 21 years now, and it’s all of our hope that you get some of that too from time to time. There is a lot of “new” on the Internet, and that’s a wonderful thing. But the combination of new and relevant just can’t be beat! So if you’ve got anything you want to hear more about, let us know.