A reasonable selection of the Hackaday readership will have had their first experiences of computing on an 8-bit machine in a black case, with the word “Sinclair” on it. Even if you haven’t work with one of these machines you probably know that the man behind them was the sometimes colourful inventor Clive (now Sir Clive) Sinclair.

He was the founder of an electronics company that promised big results from its relatively inexpensive electronic products. Radio receivers that could fit in a matchbox, transistorised component stereo systems, miniature televisions, and affordable calculators had all received the Sinclair treatment from the early-1960s onwards. But it was towards the end of the 1970s that one of his companies produced its first microcomputer.

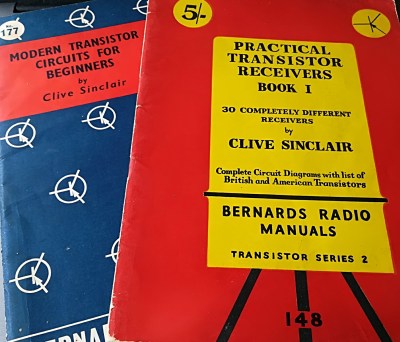

At the end of the 1950s, when the teenage Sinclair was already a prolific producer of electronics and in the early stages of starting his own electronics business, he took the entirely understandable route for a cash-strapped engineer and entrepreneur and began writing for a living. He wrote for electronics and radio magazines, later becoming assistant editor of the trade magazine Instrument Practice, and wrote electronic project books for Bernard’s Radio Manuals, and Bernard Babani Publishing. It is this period of his career that has caught our eye today, not simply for the famous association of the Sinclair name, but for the fascinating window his work gives us into the state of electronics at the time.