Amateur radio operators have played a longstanding game of “Will It Antenna?” If there’s something even marginally conductive and remotely resonant, a ham has probably tried to make an antenna out of it. Some of these expedient antennas actually turn out to be surprisingly effective, but as we can see from this in-depth analysis of the characteristics of tape measure antennas, a lot of that is probably down to luck.

At first glance, tape measure antennas seem to have a lot going for them (just for clarification, most tape measure antennas use only the spring steel blade of a tape measure, not the case or retraction mechanism — although we have seen that done.) Tape measures can be rolled up or folded down for storage, and they’ll spring back out when released to form a stiff, mostly self-supporting structure.

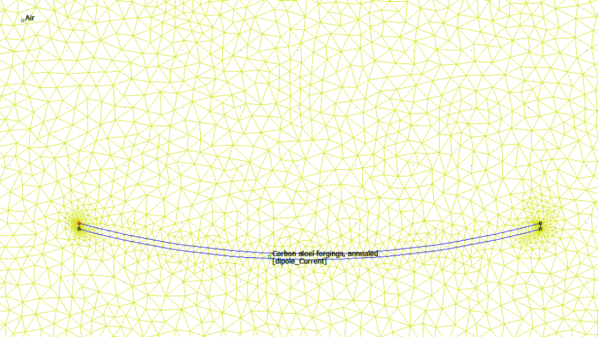

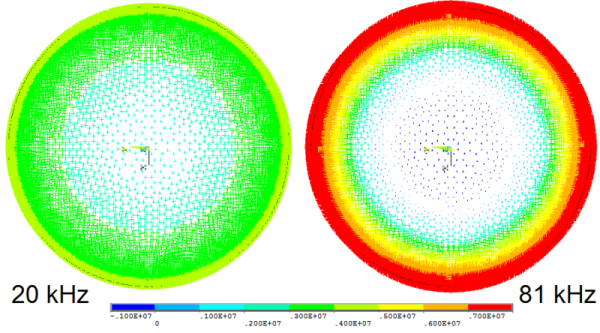

But [fvfilippetti] suspected that tape measures might have some electrical drawbacks, thanks to the skin effect. That’s the tendency for current to flow on the outside of a conductor, which at lower frequencies on conductors with a round cross-section turns out to be not a huge problem. But in a thin, rectangular conductor, a little finite element method magnetics (FEMM) analysis revealed that most of the current is carried in very small areas, resulting in high electrical resistance — an order of magnitude greater than a round conductor. Add in the high permittivity of the carbon steel material of the blade, and you end up something more like what [fvfilippetti] calls “a tape measure dummy load.

One possible solution: stripping the paint off the blade and copper plating it. It’s not clear if this was tried; we’d think it would be difficult to accomplish, but not impossible — and surely worth a try.