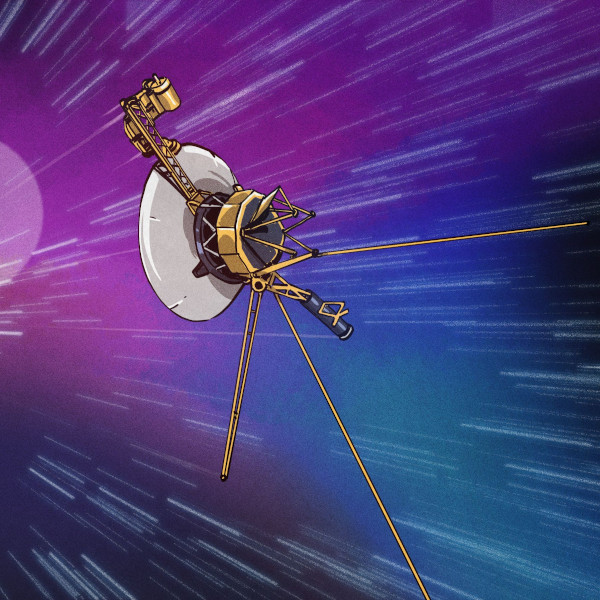

Launched aboard the Space Shuttle Columbia in July of 1999, the Chandra X-ray Observatory is the most capable space telescope of its kind. As of this writing, the spacecraft is in good health and is returning valuable scientific data. It’s currently in an orbit that extends at its highest point to nearly one-third the distance to the Moon, which gives it an ideal vantage point from which to make its observations, and won’t reenter the Earth’s atmosphere for hundreds if not thousands of years.

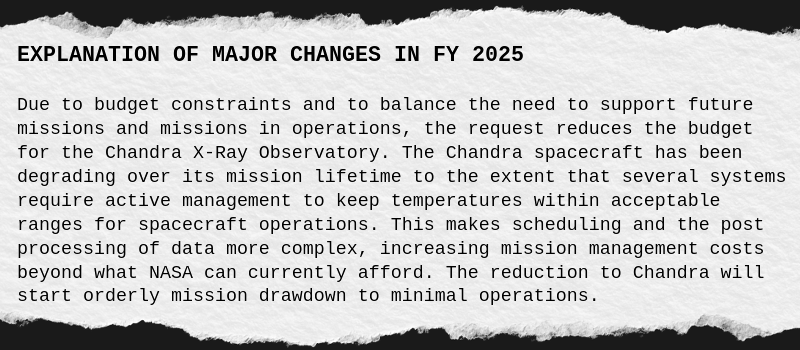

Yet despite this rosy report card, Chandra’s future is anything but certain. Faced with the impossible task of funding all of its scientific missions with the relative pittance they’re allocated from the federal government, NASA has signaled its intent to wind down the space telescope’s operations over the next several years. According to their latest budget request, the agency wants to slash the program’s $41 million budget nearly in half for 2026. Funding would remain stable at that point for the next two years, but in 2029, the money set aside for Chandra would be dropped to just $5.2 million.

Drastically reducing Chandra’s budget by the end of the decade wouldn’t be so unexpected if its successor was due to come online in a similar time frame. Indeed, it would almost be expected. But despite being considered a high scientific priority, the x-ray observatory intended to replace Chandra isn’t even off the drawing board yet. The 2019 concept study report for what NASA is currently calling the Lynx X-ray Observatory estimates a launch date in the mid-2030s at the absolute earliest, pointing out that several of the key components of the proposed telescope still need several years of development before they’ll reach the necessary Technology Readiness Level (TRL) for such a high profile mission.

With its replacement for this uniquely capable space telescope decades away even by the most optimistic of estimates, the potential early retirement of the Chandra X-ray Observatory has many researchers concerned about the gap it will leave in our ability to study the cosmos.

The Sky Through X-Ray Vision

Just a few years after the launch of the incredibly powerful James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), it might seem odd that scientists are concerned about the fate of an observatory that was launched 25 years ago.

But for all the capabilities of the JWST, making observations in the X-ray spectrum simply isn’t one of them. It was designed almost elusively for performing infrared astronomy, a specialization to which it owes many of its unique design elements. Other well known space telescopes, such as the European Space Agency’s Euclid or the legendary Hubble Space Telescope operate primarily in the visible spectrum.

It’s not that Chandra is the only space telescope capable of x-ray imaging — but it’s unquestionably the best we currently have. Of course, this was by design. While most of the other x-ray telescopes in space are either secondary payloads or otherwise relatively small, Chandra was designed and built as one of NASA’s flagship missions. Like Hubble it was part of the Great Observatory program, and was intended to push the state-of-the-art in detection technology for its particular slice of the electromagnetic spectrum, setting the standard for decades to come.

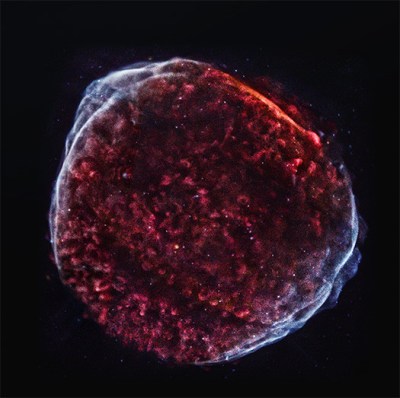

Compared to optical or IR telescopes, x-ray telescopes are ideal for directly imaging high-energy objects such as supernovas and galaxy clusters. It’s also possible to make indirect observations by studying how a given object reflects or absorbs ambient x-ray energy. X-ray telescopes are also key for studying what might otherwise be invisible, such as black holes and dark matter.

Rising Temps, Rising Costs?

According to the NASA budget request, winding down Chandra’s funding to what it calls “minimal operations” by 2029 isn’t just some arbitrary decision. The report specifically cites increased program costs directly related to the age of the spacecraft, or more specifically, the extra effort that’s now required to get usable data from onboard systems which are increasingly operating out of spec:

In a post titled “A Letter to the Chandra Community“, program director Dr. Patrick Slane addresses these NASA claims directly. While he acknowledges that Chandra has suffered system degradation, he points out that it’s hardly unexpected for a spacecraft of this age. Despite being designed for a planned mission duration of 5 years, Chandra is approaching 25 years in orbit. He also admits that it’s made observations more difficult than they were when the observatory was launched.

That said, Dr. Slane argues that Chandra’s rising operating temperature isn’t a new problem, and was first identified as far back as 2005. Over the years the teams have been able to characterize the temperature fluctuations, which vary depending on orbital position and spacecraft attitude, and develop new models that allow them to compensate for any thermally-induced shifts in the data. He says these efforts have been greatly successful, and that even today, Chandra’s observation efficiency “far exceeds the initial requirements for the mission.”

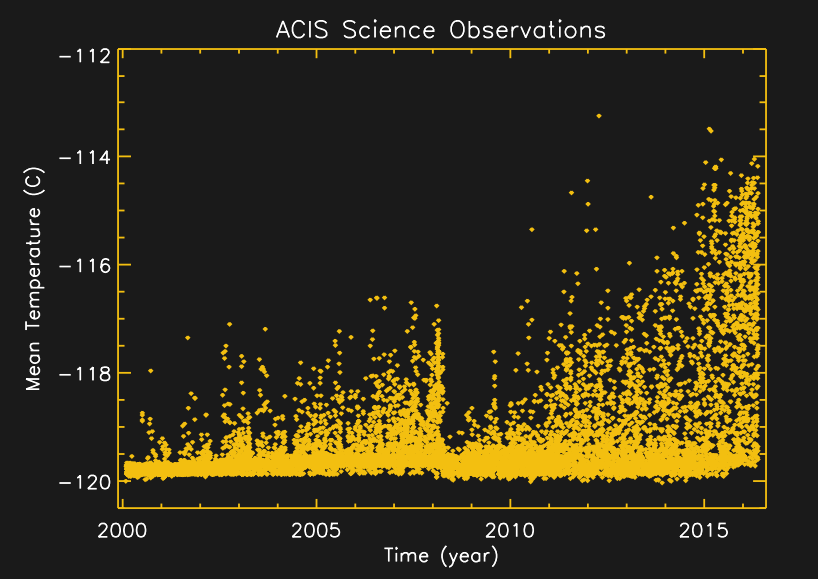

The documentation for this isn’t difficult to find. In the 2016 paper “Evolution of temperature-dependent charge transfer inefficiency correction for ACIS on the Chandra X-ray Observatory“, it’s explained how the responsiveness of Chandra’s Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS) had changed since launch, and how teams on the ground were adjusting to the system’s new characteristics.

While the paper notes that the ACIS had suffered some radiation damage, it identifies the reduced effectiveness of Chandra’s thermal control systems to have introduced the largest changes. At the time of publication, now nearly a decade ago, it was already clear that the ACIS temperature was on the rise. The paper notes that in 2000, 99% of observations were made at what it considers “cold” temperatures of below -119.2° C, but by 2015, that figure had dropped to just 33%.

The paper explains that, after gathering sufficient calibration data, algorithms were developed to compensate for the increasingly erratic ACIS temperatures. That said, it did note that the team’s initial assumptions that the temperature fluctuations would remain relatively minor were already being challenged. Should instrumentation temperature continue to climb higher, more data would need to be collected to verify their compensation software still worked as expected.

Still, the authors closed the paper with the belief that Chandra would still be able to meet its performance goals even in theis newly dynamic thermal environment.

The Fight Has Only Just Begun

Between the published data on telescope’s instrumentation, and the passionate response of Dr. Slane, it would seem the Chandra story isn’t quite over yet. There’s an excellent case to be made that the thermal issues with the observatory, while a valid and documented concern, are a largely solved problem that doesn’t require any additional financial outlay. Why the NASA budget request seems to indicate otherwise is beyond the scope of this article, but with the ever-rising cost of the Artemis program, it’s not hard to imagine that the agency is looking to justify cost cutting measures wherever it can.

At the end of his letter, Dr. Slane notes that the Chandra X-ray Observatory would be going through a review in April to further clarify its budgetary needs going forward. After giving the program a closer look, and perhaps after feeling a bit of pressure from the astrophysics community, NASA may yet change its plans for this valuable instrument.

A designed lifetime being 1/5th the current useful lifetime of a mission is so NASA. Pretty amazing track record on that

Let’s just remember all the recent (last 30 years) missions to mars, all of which had a life way longer than expected and planned.

Are you guys giving accurate estimates?

Are you children?

How are you going to get a reputation as a miracle worker with an attitude like that.

(para) Scotty, one of the dreks.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mars_rover#:~:text=As%20of%20May%202021%2C%20there,Perseverance%20(2021%E2%80%93present).

I wish NADA made Smartphones.

Actual useful life of 20 years for a product that normally is obsolete after 5? Also, price tag would be so high that you would need a government subsidy to buy one.

I wish NASA made EVs, though.

It wasn’t *designed* for 5 years – that’s bad wording on Hackaday’s part. NASA only specifies short original mission durations because otherwise you need to plan out *personnel and support* that far. It’s a funding thing, not a “we only expect 5 years” thing.

Yeah yeah but the other way sounds much more impressive so

Mission planning starts with a science goal: We want to make x observations to advance y.

Then a time estimate is attached to that goal (this will take 5 years). Then the spacecraft is designed to make it likely to survive at least that long. At the end of that mission you’re in the middle of the bathtub curve so if you made it that far, it’s likely to last a lot longer, if your mission does not depend on consumables (fuel for attitude adjustment, coolant etc.).

Always more important to shoot more meat into space than to do something at least possibly useful.

It is in fact more important to shoot meat into space. Utilitarianism is a trap. We exist to bodily go places, not to hoard spreadsheets and PNGs

So go on your own dime?

Be glad people didn’t say that to Columbus.

If we took that attitude then nobody would have ever gone anywhere. These things are a team effort and we will drag you kicking and screaming and complaining along

… and yet you will fail.

Not to mention, humanity spreading to other worlds will make it much more likely that we survive as a species.

Also, what’s up with these people’s obsession with describing humanity as “meat?” Meat suits, meat robots, meat this meat that. It’s creepy. Epically reddited Dr Richard Dawkins, tip of the fedora to you

Greet and meat.

B^)

Stop it. You’re making me feel hungry.

(Chuckle!)

Maybe a consortium of Universities and Researchers should “buy” Chandra from NASA to keep it running?

This looks like a typical beureacratic ploy to get additional funding by proposing a cut that makes little sense on the merits but is not likely to be supported by Congress. NASA is likely counting on the public lobbying their senators and representatives to overrule this cut. It is not a bad gambit. I plan to push back, and encourage others to as well.

I would like to see congress go further and mandate that NASA provide a mechanism to transition responsibility for operating missions that are past planned end of life to a non-profit or the private sector.

We could probably fund Chandra ops through a Kickstart. Who’s game?

I’ll put my 2 cents in, literally 2 cents, I’m poor but it’s still a good idea.

In the graph above it shows the mean temp cooling down in early 2008 before heating up at a higher rate starting in late 2008. Why? Any idea what happened at that time?

I was curious about that too. I found this paper (from NASA via archive.org) https://web.archive.org/web/20190430034803id_/https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20140005792.pdf

Thanks to [Shannon]’s link, they reported a heater element was switched off in 2008.

I understand that actual data received require more post-processing using some algorithms developped for that purpose. So basically it requests some more time and more computing time/power to get an image. But beside that, why does this cost dozens of millions dollars? It’s really a genuine question, i don’t understand what in this process costs so much money…

That was my thought as well. It’s not like they are sending fuel up there every year.

Think the maintenance of satellite dishes, the employment of many PHDs and staff, the actual real state used to operate mission equipment, actual mock-ups and physical “twins”, and so on.

PhDs are cheap.

Applied math/Physics PhDs make decent code monkeys. Just shake a tree on the nearest campus. Beware, some are large. If they land on you, it will hurt.

They are talking about getting the budget down to 5million/year. That’s 10-20 staff, or 5-10 staff and a budget slice for coms.

Gotta’ move those available funds from actually scientifically productive efforts like this to SPAM in a CAN national prestige Space Race v2.0 to the lifeless dusty ball that is our moon where no human has been for over 50 years FOR GOOD REASONS.

The real goal of SLS/Artemis/etc is to keep a bunch of factories that used to make Space Shuttle bits going so that the people who work in those factories will continue to support the politicians that support them (by forcing NASA to keep buying the parts those factories make)

No they don’t, no they won’t. Stop boosting political BS. That’s all this is. They’re playing chicken, and by boosting the story, you’re rewarding them for doing so. Call their bluff. They’ll cut something much less worthwhile.

Naughty Nasa.

I’d hate to see this shut down since my first paid programming position was a summer job at Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, writing a program to plot data from the Uhuru x-ray satellite. The work there on x-ray mirrors went into Einstein and then Chandra. (Uhuru did not have a telescope, just a rotating collimator)