It’s already been more than fifty years since a human last stepped foot on another celestial body, and now that NASA has officially pushed back key elements of their Artemis program, we’re going to be waiting a bit longer before it happens again. What’s a few years compared to half a century?

The January 9th press conference was billed as a way for NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and other high-ranking officials within the space agency to give the public an update on Artemis. But those who’ve been following the program had already guessed it would end up being the official concession that NASA simply wasn’t ready to send astronauts out for a lunar flyby this year as initially planned. Pushing back this second phase of the Artemis program naturally means delaying the subsequent missions as well, though during the conference it was noted that the Artemis III mission was already dealing with its own technical challenges.

The January 9th press conference was billed as a way for NASA Administrator Bill Nelson and other high-ranking officials within the space agency to give the public an update on Artemis. But those who’ve been following the program had already guessed it would end up being the official concession that NASA simply wasn’t ready to send astronauts out for a lunar flyby this year as initially planned. Pushing back this second phase of the Artemis program naturally means delaying the subsequent missions as well, though during the conference it was noted that the Artemis III mission was already dealing with its own technical challenges.

More than just an acknowledgement of the Artemis delays, the press conference did include details on the specific issues that were holding up the program. In addition several team members were able to share information about the systems and components they’re responsible for, including insight into the hardware that’s already complete and what still needs more development time. Finally, the public was given an update on what NASA’s plans look like after landing on the Moon during the Artemis III mission, including their plans for constructing and utilizing the Lunar Gateway station.

With the understanding that even these latest plans are subject to potential changes or delays over the coming years, let’s take a look at the revised Artemis timeline.

2025 – Artemis II

Originally scheduled to happen by the end of 2024, Artemis II now has a No Earlier Than (NET) date of September 2025. Beyond being pushed back a year, the mission itself has not changed, and will still see four astronauts travel from Earth orbit to the Moon and back aboard the Orion capsule. This mission is roughly analogous to Apollo 8 in that the crew will operate their craft within close proximity to the Moon, but won’t attempt to land. Unlike Apollo 8 however, Artemis II will not enter lunar orbit and instead make a single close pass around the far side of the Moon at a distance of approximately 10,000 kilometers (6,200 miles).

NASA says the delay is largely due to three major technical issues with the Orion capsule that need to be addressed before it can carry astronauts:

Heat Shield Performance

While the Artemis I mission in 2022 was a complete success, engineers did notice greater than expected erosion of the AVCOAT heat shield material that protects the Orion capsule during reentry. The shield is designed to be ablative, and NASA says there was still a “significant amount of margin” left on the spacecraft, but the fact that the damage didn’t track with pre-flight simulations has mission planners concerned.

As Artemis II will be flying a very similar mission profile, engineers wanted to take a closer look at this anomaly, looking to not only improve their simulations but to see if there is some way the erosion could be reduced on future flights.

Amit Kshatriya, the Deputy Associate Administrator for the Moon to Mars Program, says that team feels they have a good understanding of the issue, and hope to have their investigation completed by spring.

Life Support Design Flaw

A design flaw found in certain life support components currently being installed in the Orion capsule for Artemis III lead to the decision to go back and replace the hardware that had already been installed in the Artemis II capsule. The components were explained to be responsible for controlling various valves in the system, including those used by the carbon dioxide scrubbers.

Given the fact that the life support system in the Artemis II capsule had already passed its qualification checks before the flaw was identified, some consideration had been given to using the flawed components, perhaps with some procedural changes to avoid triggering a malfunction. But ultimately it was decided that crew safety couldn’t be compromised, and that the hardware needed to be replaced.

Unfortunately, with assembly of the the Artemis II capsule so far along, accessing the components in order to replace them is a considerable undertaking. The capsule will also have to redo various qualification checks once reassembled, further delaying its completion.

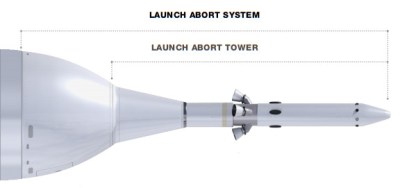

Potential Power Loss During Abort

The final major issue was identified was with the Orion capsule’s batteries, which testing showed could fail when subjected to the vibrations expected during an in-flight abort.

Should the batteries fail after the solid-fuel rocket motors in the Launch Abort Tower pull the Orion capsule away from the crippled or damaged booster, the crew could be left without power at a critical moment.

Should the batteries fail after the solid-fuel rocket motors in the Launch Abort Tower pull the Orion capsule away from the crippled or damaged booster, the crew could be left without power at a critical moment.

Kshatriya said the investigation into this particular issue is still in the early stages, and a decision has yet to be made on how it will be addressed. But as with the life support electronics, should the decision be made to remove the batteries, it will likely add several additional months to the capsule’s assembly and testing time.

2026 – Artemis III

Artemis III is also being pushed back by roughly one year, in part due to the delay of Artemis II. As a number of major systems are reused from one Orion capsule to the next (such as the avionics), technicians need several months to remove those components and install them in the newer spacecraft.

But even if Artemis II hadn’t been pushed back, NASA says there are two major areas of development that need more time before they can put astronauts back on the Moon:

Human Landing System

The Human Landing System, or HLS, is the official Artemis designation of the customized version of SpaceX’s Starship that will take astronauts down to the lunar surface. NASA says they are satisfied with the pace of development for Starship, which should make its third test flight as soon as next month. But there are concerns about the in-space refueling procedure that will be necessary for HLS to reach the Moon, which has never been attempted in space.

For SpaceX’s part, they believe that many of the key elements of orbital refueling can be tested and perfected at a smaller scale, allowing them to rapidly iterate until the bugs are worked out. Jessica Jensen, VP of Customer Operations and Integration at SpaceX, also said that the lessons the company is currently learning on transporting and loading the vehicle’s cryogenic propellants on the ground will be directly relatable to how they will perform similar operations in orbit.

There’s also the matter of developing a Starship-Orion docking mechanism that will allow the crew to transfer from one vehicle to the other. This is not so much a technical challenge, as SpaceX already has real-world experience in building docking hardware for the Crew Dragon, but will still require time to develop and test.

Finally, Starship still needs to complete an uncrewed demonstration mission that includes all the steps required to complete Artemis III. That means launching into Earth orbit, being refueled, travelling to the Moon, successfully landing, and of course, lifting off the surface and returning to space. This test is currently scheduled for 2025, which will give SpaceX and NASA time to go over the results and make any necessary changes to the final mission.

Next-Generation Spacesuits

After determining that their own version wouldn’t be ready in time, NASA turned to commercial partners to develop a next-generation spacesuit for use on the lunar surface. Axiom Space, who are currently orchestrating private missions to the International Space Station and hope to eventually build their own orbital facility, ended up winning the competition.

NASA gave the public a peek at what the new suits would look like in March of 2023, and then in October, Axiom announced they were partnering with Italian luxury designer Prada to improve the design. Since then there hasn’t been much news about the suits or their development, but given the fact that the suits have been identified as one of the things holding Artemis III back, we can assume things aren’t progressing as quickly as hoped.

2028 – Artemis IV

The date for Artemis IV, the first post-landing mission of NASA’s lunar program, actually hasn’t changed. It was always scheduled for 2028, but details on what the mission would entail were always a little vague.

That situation hasn’t improved by much, but we now at least have confirmation that NASA plans to have the first modules of the Lunar Gateway station ready in orbit around the Moon by the time the Artemis IV astronauts arrive. No launch date for these modules, which are slated to fly on a Falcon Heavy, was given — but they’d have to be on their way to the Moon by early 2027 at the latest for the timing to work out.

A Block 1B version of the SLS, with greatly improved payload capacity, will send both an Orion capsule and the International Habitation Module (I-HAB) towards the Gateway, where an upgraded version of the Starship HLS will be waiting. After the astronauts deliver the module to the station, they will descend to the surface to complete further mission objectives.

Given how far out Artemis IV is, there’s little point in speculating what kind of hardware delays it could run into, but clearly there are many moving parts involved. Not only do the two first modules of the Gateway need to be completed and launched to the Moon, but the I-HAB needs to be ready, as does SLS 1B.

To further complicate matters, the mass of the combined SLS 1B and I-HAB is so great that a new launch platform will need to be used, a project that has already been delayed and is significantly over budget. In a June 2022 report from NASA’s Office of Inspector General, it was estimated that the new launch platform wouldn’t be ready until at least the end of 2026.

Terms Subject to Change

It was an open secret that the previous Artemis timeline wasn’t realistic — if astronauts were to be headed to the Moon before the end of 2024, it’s likely we would have already seen the SLS rocket they’ll be riding to orbit in going through its final tests. But until the announcement was officially made, NASA had to keep telling the public that things were on track.

Even this revised timeline is arguably pushing what the agency is capable of, given their divided attention and relatively limited budget. During the press conference, Kshatriya admitted that the 2026 date for Artemis III is “very aggressive”, suggesting that this isn’t the last time NASA is going to have to shuffle their plans around before they can finally put some fresh boot prints on the lunar surface.

I don’t follow the space program much; but this story doesn’t surprise me at all, thanks to this video which came up in my YT recommendations a month ago:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OoJsPvmFixU

At over an hour it may require some patience; but it’s probably worth it for those interested in a deep dive into the challenges NASA is facing and the reasons for them not being as far along as they expected to be. Not surprisingly, it seems that some of the challenges ultimately arise from organizational and political issues as well as scientific ones.

This video is often cited (hell, it’s linked multiple times in these comments), but it doesn’t stand up to any kind of mental scrutiny. Makes it perfect YouTube fodder, I suppose…

This video is like asking why we use big complex jet aircraft to fly around when hot air balloons worked just fine before. Or what’s the point of putting a steam turbine on a ship when we have these perfectly good sails.

Artemis is not Apollo. You can launch to the Moon in one rocket if you’re willing to cram the crew in sardine can for the whole trip and bring back a few hundred pounds of rocks.

But Starship is like landing a office building on the Moon. It’s large enough to contain its own laboratories and equipment, and bring tons of cargo to the surface. So what if it takes multiple flights to load the propellants, that’s the whole reason they are developing it to be rapidly reusable.

It’s actually worse than that, if you think about it. Some of the biggest technology developments we’ve made since Apollo are in-orbit robotics, the development of (at least partially) reusable heavy-lift vehicles, and long-term space exposure.

Artemis is *designed* around those things. It’s not a BFR because we’ve gotten heavy lift down to $100M/launch and there will soon be *three* heavy-lift vehicles on the market, and you’d be silly not to utilize them.

It’s inevitable that a public megaproject such as this would lead to political issues, that should always be budgeted in.

Whenever I heard anything about Artemis, I take it with a grain-of-salt, especially after seeing this video: https://youtu.be/OoJsPvmFixU

Thanks for the link. A lot of what this guy says makes sense.

What I think the people working on nowadays space programs do miss,

is to make a step back and see themselves from the point of view of an outsider.

They’re so busy re-inventing the wheel,

if they could simply have learned from the past.

Great minds have worked on the Apollo program,

it would be a waste not to learn from their achievements.

The whole way of approaching things has changed since those days, maybe.

Instead of handling or mastering bad situations, the focus seems to be on avoiding them by all means. But that’s not realistic.

Unexpected problems may always be occur. It’s better to expect them and to learn to improvise and handle them.

Since the shuttle accident was mentioned: The last shuttle disasters were horrible, but it wasn’t all a technological problem.

The damage on the Columbia was known before re-entry, afaik.

Back then I’ve followed the drama live on TV, the news speakers mentioned some problems.

It was time pressure and fear that lead to this tragedy, maybe. Political reasons.

An alternative would have been to go back to ISS or wait for a rendezvous with a Russian transporter, not sure.

If there’s anything a new program needs, then it’s open communication.

And the willingness to swallow pride and accept help.

Someone should think that professionals and nations would act like mature, grown up individuals.

I think that if there’s a construction issue that holds back development or if there’s a problem that causes harm to the passengers/astronauts,

it would be a sign of maturity to ask for assistance and to discuss this issue with other space agencies, with international partners and do some sort of joint brainstorming.

“They’re so busy re-inventing the wheel,”

Apollo landed a ~5 metric ton lander on the easiest place to reach on the Moon.

Artemis is targeting a 50-85 metric ton lander on the *hardest* to reach place on the Moon.

It’s like you’re looking at a company struggling to figure out a construction vehicle’s suspension system and saying “what’s so hard, just build it like a bicycle tire.” Apollo’s goal was to *get* to the Moon. Artemis’s goal is to *stay* there.

Well, I don’t know what to say.

If they want to go the hardest route, unprepared.. I’m speechless.

To me, it’s like saying “hey, but they want to climb a mountain in shorts and sandals, without any safety line!”

No. It’s like saying “We’re going to climb that mountain. What’s it going to take?”

They aren’t running up the side of Everest in shorts and flip-flops.

They’ve looked at it and know what the problems are, and that there are problems ahead that they haven’t yet seen – but they ARE going to solve them.

In my opinion, after 50 years of rest, it would be wise to start practicing first, again. With smaller, humble goals. Using technology that works. Optimization can be done anytime after this, still.

But no, NASA and friends are like an old, bedridden person that tries to bet fit without any training, to join a marathon run. It’s no one wonder they can’t get anything meaningful done. The approach is unwise, not to say stubborn.

“it would be wise to start practicing first, again.”

They did.

In 2022.

It worked.

It was called – unsurprisingly – “Artemis I.”

@Pat Right, Artemis 1. Under the command of Cmdr. Snoopy and pilot Shaun.

“Under the command of Cmdr. Snoopy and pilot Shaun.”

Yes. Uncrewed. Just like Apollo 4, 5, and 6. And why were Apollo 4, 5, and 6 uncrewed?

Because it cost three lives to learn that you test with uncrewed missions first.

(and for any other Apollo history buffs, yes I know that Apollo 1 wasn’t the first flight and there were three uncrewed launches before it, too – but it was the first orbital flight of the CSM, and going from “suborbital unmanned” to “orbital manned” was probably aggressive)

Hey it’s the chicken guy! Excellent video by a guy with infinitely more tact and communications skills than me, thank you for posting.

Not changed however is that through the Artemis program, we will see the first woman and first person of color walk on the surface of the Moon.

When social issues start to play a large part of who will crew, it doesnt take a genious to figure out this ship wont sail for a long long time ( if ever ). My money is on the chinese being the first persons of “colour” to walk the moon.

“When social issues start to play a large part of who will crew”

This is *entirely* backwards: social issues played a large part of who crewed *Apollo*. There were plenty of qualified people of color at the time of Apollo. They just weren’t selected because of, um. Reasons.

If you had a completely blind astronaut selection process you’d still end up with the first woman and person of color on the Moon for Artemis because *they’re just as qualified*.

+1

And that’s a good thing! Representation matters. I mean at the end of the day, they all passed rigorous astronaut training, and anyone who has a problem with this might just be a touch prejudiced…

It’s a laudable goal to include a person of color and a woman in the Artemis crew. I just hope that PC didn’t get in the way and that those two individuals weren’t just the top people in those two categories but that the entire crew consists of the top four of all qualified individuals and only coincidentally is one of them female and the other of color.

“what the agency is capable of, given their divided attention and relatively limited budget.”

It’s not really the agency here, it’s the contractors (SpaceX primarily).

I still think the main reason for the delay is because NASA’s initial plan assumed that SpaceX would be perfectly happy with a contract to launch a ~40-ton 3-stage lander via 3-4 Falcon 9 Heavy launches, and back in ’18 this timescale wasn’t totally crazy.

But instead SpaceX is like “nah you keep your little subcompact, we wanna build an super-duper offroad SUV and we can totally do it for the same price” and NASA was like “um… OK.”

If SpaceX can do it, though, man, the overall Artemis program will be a massive success, because a cheap reusable vehicle like Starship is *immensely* valuable long-term. I just don’t think NASA will really get the credit for it because everyone just associates Artemis with SLS, even though the project was *very clearly* designed around minimal SLS use plus cheap heavy-lift.

I agree that there may be good reasons, but I can’t help but think about this as a soapbox racing.

It’s not about a common goal, getting to the moon, but who’s first and who has the best machine.

I wished the responsible people would work as a team, and everyone would contribute one piece to the puzzle.

But that’s just my two cents.

“but I can’t help but think about this as a soapbox racing.”

The rest of the world calls it “capitalism.”

Maybe, but it doesn’t make things better, does it?

Just think of the original Alien movie (’79) and Waylan company. Or Outland (’81).

These films did criticize the commercialization by exaggerating things.

It was meant as unrealistic side blow in the day, to shock the audience.

Now it’s becoming a reality, more and more. And people love it.

I wonder, what’s worse: if something is driven out of national pride or plain greed/profit/exploitation?

Personally, I think that humanity should be grown up by now and past the money thinking..

Space is vast. And hostile. Up there is now law, except the common law we all agree upon.

Once space explor.. space exploitation is driven by money, morals will be secondary.

Companies don’t need to justify themselves except in front of their shareholders.

Nations are different, they have to justify in front of their citizens.

Nations must follow international laws and agreements, they must care about life of citizens, of astronauts.

Companies are not like that. They will “walk over corpses” to reach their goals.

The same happened in the days of the Titanic accident.

In that era, radio operators were company employees.

One radio operator usually didn’t talk to the radio operator of another radio company. It was against the company’s rules.

Even in an emergency, they hesitated because of fear loosing their job.

After Titanic accident happened, all radio operators were being *required* to respond to emergency calls originating by radio operators by rival companies. That’s what nations agreed upon. A company wouldn’t do that.

You could say the same thing about air flight.

Capitalism, competition, complete chaos in the air, no cooperation, etc.

Oh, wait. No air flight is regulated. It is the safest form of transportation.

Space flight will be regulated. There will be competition between companies, but that’s how you advance technology.

“Space flight will be regulated. There will be competition between companies, but that’s how you advance technology.”

Yup. You could imagine some, I dunno, government agency interacting with these companies requiring them to hit certain milestones and demonstrate capabilities before they’re used for human spaceflight.

Oh, wait…

“Maybe, but it doesn’t make things better, does it?”

Um. It certainly did with the medium-lift rocket industry!

“They will “walk over corpses” to reach their goals.”

We’ve been using commercial companies to deliver crew to the ISS via the Commercial Crew Program for 3 years now. They’ve launched 28 people so far on 6 launches with more planned including a second company and vehicle. There have been exactly zero incidents.

Your opinion of the way these companies work is just totally misplaced. NASA isn’t just throwing money at them and saying “build it!” It’s a total partnership between industry and government and it’s been an unqualified success so far.

Yeah it turns out that competition turns out better results than kumbaya, but this will never change anybody’s mind because these issues are so fundamental that they are quasi-spiritual.

Engineering a spacecraft through the potluck system is also dubious.

The agency NASA that sent people to the moon doesn’t exist anymore. The current thing occupying NASA’s corpse is not capable of doing it, and never will be. Their philosophy will never permit them to take the necessary risk level, it will always be put off, and the quality of their people is far poorer than the ones who did it half a century ago.

Amen.

Myself, I think everyone forgot how hard it is to put people in space with an unproven system. NASA always had to have a multiple factor on their time estimates

These are not one but several unproven systems, layering the risk and multiplying it. I really don’t see the funding pipe staying open long enough to accomplish any of this, it’s obviously more NASA vaporware and the people buying it again strike me as very naive and overly optimistic in a field that abhors inappropriate optimism.

Bring back meritocracy and these problems will work themselves out.

Is someone a bit salty about astronaut selection?

He didn’t sound salty, but it’s the correct analysis of consistent failure—and it’s not just about the astronauts themselves. In the sixties, selection criteria were strictly oriented towards success. Now it’s undeniable that the criteria are primarily political, and Lysenkoism results.

I know that a few years ago the whole meta for online argument was to try and paint your opponent as the one getting mad, but it doesn’t really work anymore if people are obviously not mad.

Given his misogynistic response to my comment was slightly unhinged, and got moderated out, I don’t think I was far off the mark.

I hope you are not inferring that if meritocracy was actually used, that certain (currently preferred) people would not qualify. That would re-enforce, not reduces, “ist” thinking.

And, that is why meritocracy is the ONLY correct solution – not just in high tech jobs – everywhere.

Good luck finding a way to quantify “merit.” I’m sure it’s a solved problem and there have never been any problems with that historically.

Hmmmm…I’m not understanding what is so hard about objectively rating performance.

The only way that I could see it being difficult is if one doesn’t have concrete requirements and objectives for positions under them, or are not tracking performance of their staff, or simply do not understand the positions they manage.

“The only way that I could see it being difficult is if one doesn’t have concrete requirements and objectives for positions under them, or are not tracking performance of their staff, or simply do not understand the positions they manage.”

So… you *are* seeing what’s so hard about objectively rating performance.

“So… you *are* seeing what’s so hard about objectively rating performance.”

Not really, the examples I gave are easily corrected to objective performance criteria through training. Nothing hard at all about implementing objective judgements.

“Not really, the examples I gave are easily corrected to objective performance criteria”

So you’re saying… they’re examples of poor performance by the people who are evaluating candidates? And how do you objectively measure that?

It’s turtles all the way down.

“And how do you objectively measure that?”

Easy. If they hire candidates that do not meet the job requirements then they fail their objectives as managers and should be fired.

“It’s turtles all the way down.”

It is turtles all the way down for people that don’t want to be judged.

“Easy. If they hire candidates that do not meet the job requirements then they fail their objectives as managers and should be fired.”

No, I asked about the person who *created* the job requirements. How do you prove that objective requirements were objectively chosen? You can’t derive job requirements from the fundamental laws of the Universe or something, and it’s *very* common to sculpt your candidate base with seemingly objective requirements that are not, in fact, related to the job. That’s exactly what happened in Griggs v Duke Power.

This is why I said “I’m sure there have never been any problems with that.” Fair hiring practices are hard.

The Griggs decision is actually along the lines of my point.

“How do you prove that objective requirements were objectively chosen?”

By making the objectives task and performance oriented rather than property or attribute oriented.

A property or attribute of a person are things like degrees or credentials or certifications, but also, gender, race, age, nationality, etc. There are people that think these things are important. But, with only a few exceptions, they are not and those people are wrong. Duke was doing that, and they were wrong. NASA appears to be doing that too, and they are also wrong.

What is important are objectives that are task oriented and related to the primary mission of the organization.

For example, a private company wants to make money mowing lawns. A job requirement that the person knows how to operate and clean a lawn mower in a safe manner is valid. A job requirement that the person needs a college degree is not. The former is a task used by the company to make money. The latter is just an opinion that credentialed people are somehow superior.

The above example can be repeated with any job and any organization.

It would be helpful if you shared a job where the above rules cannot be applied as I could then see, and hopefully understand, an example of what you are talking about.

“By making the objectives task and performance oriented rather than property or attribute oriented.”

Yes. And in a situation like this, that’s *impossible*. In Griggs you could easily show the tests were unneeded – you just compare the performance of people on the *actual tasks*. Even there that’s still not necessarily fully objective – if there’s a reasonable accommodation that makes person A’s performance equal to person B, it wasn’t the difference between person A and person B that’s the problem, the *job* is the problem, not the person.

“It would be helpful if you shared a job where the above rules cannot be applied”

Consider Apollo. The only objectives that are actually required for those astronauts is “survive launch, land on the Moon, and return alive.” You cannot determine whether someone is capable of doing that, because *no one has*. You can’t say “OK, we’ll test to see if you can do this.”

So what do you do? You make reasonable guesses. Flight performances, simulator results, etc. But those are *guesses*. You could say “but they’re all task and performance oriented” but the people *making* those tests and simulators have biases of their own.

I’m not saying you can’t have objective criteria contribute to a hiring process. I’m saying that you have to evaluate the *results* of the hiring process to evaluate the criteria you used. You can’t just point to the criteria alone. That’s basically the Griggs decision in a nutshell.

“If there’s a reasonable accommodation that makes person A’s performance equal to person B, it wasn’t the difference between person A and person B that’s the problem, the *job* is the problem, not the person.”

That’s a variant of property based judgement and therefore wrong.

The two applicants are objectively not equal – one of them will require the company to subsidize their needs, whereas others do not require this subsidy. Not only is that not fair to the other applicants who can do the job without the subsidy, but all the other prior employees who were hired do not get any bonus money equal to the subsidy.

Finally, trying to equate property based judgements with performance based judgements based upon the fact that an organization may be ignorant of all that is needed to be successful is a straw man argument. No successful organization accepts a body of unknowns and blindly goes forward. Instead, they reduce the unknowns to a manageable risk and focus on what they do know to drive success (e.g. the Apollo missions).

“I’m saying that you have to evaluate the *results* of the hiring process to evaluate the criteria you used. You can’t just point to the criteria alone. ”

If a company is hiring the wrong people or they have the wrong tasks defined for jobs, or the wrong objectives in general, that company will perform badly, and perhaps even fail if the problem is not corrected before it is too late. So, that is baked into the lifecycle of a company.

“one of them will require the company to subsidize their needs,”

No. It requires the company to consider applicants before the job is created. Reasonable accomodations aren’t subsidizing the applicant. They’re the company paying for a failed job creation process.

Imagine a company designing a construction facility, and the only bathroom is male. Because they have no concept that women would apply for the job, which becomes a self-fulfilling statement. (If that sounds like no company would ever do that, this is not a hypothetical). It is not “subsidizing” to add a women’s bathroom – it’s fixing a mistake in the design process.

“It requires the company to consider applicants before the job is created.”

Why? The company’s consideration should be its mission and objectives related to achieving that mission. Who may or may not apply for this or that job and what they may or may not look like (or any other attributes/properties) in the future should not be a concern. Worrying about stuff like that is property based thinking and will lead to discrimination.

“Imagine a company designing a construction facility, and the only bathroom is male. ”

Sure – that saves money and makes sense if the workforce is all male. But, if they come across an applicant that is desirable due to performance, and that person happens to be female, then they either add an additional bathroom for women ($) or assign one of the existing extra male bathrooms to be used only by women (no $), or make them all unisex bathrooms (no $). That way it is handled only when needed and only when a performance based individual presents. This is also a win for the woman because these changes will be done due to the value of her performance and skill, not because she is a woman.

I think the issue at hand, from what I can tell, is that you think it is ok to discriminate as long as people like you do it because presumptively you can only have good reasons. But, if Duke Energy does it, then it is bad because they can’t have good reasons. The problem with this approach is that it says discrimination is actually OK and could even be good, as long as “good” people do it, leaving the question of who is good.

The best neutral method is performance based.

We’re talking about selecting *the best candidates* for a job.

If we say “it’s okay if a job restricts the pool of candidates because that company will go out of business” we’re not *actually* selecting the best candidates.

It’s like saying “it’s okay if Artemis doesn’t actually select the best candidates because the mission will just crash and explode and the next mission will fix that problem.”

Part of figuring out if you’re actually selecting the best candidates is to look at the candidates you’re selecting. This is entirely the point.

“We’re talking about selecting *the best candidates* for a job.”

Exactly, which is why we should only use a person’s prior performance mapped to the objectives of the job to determine who is the best.

Those with the superior performance get selected which increases the chance of success of the organization, assuming the job objectives are aligned properly.

Now, if I’m understanding you correctly, you’re going to come back and say that we cannot possibly have the job objectives aligned correctly because we didn’t take into account the subjective value of some arbitrary set of properties of people when coming up with the objectives. That doesn’t make any sense as that doesn’t reduce the risk of selecting job objectives unrelated to the mission of the company or organization.

Regarding the company going bankrupt and the Aretimis mission examples : A company will not immedtially go bankrupt – it will receive feedback that something is amiss (making less money) and management must review the current environment and adjust objectives accordingly. They will only go bankrupt if they refuse to react to the feedback.

With regards to Artemis – that is exactly how risk-averse programs are done : starting small and doing iteration upon iteration – learning what worked and what didn’t and then feed that back into the process for the next iteration. The original space program was done that way. This approach reduces the risk of accidents and failure. And, it is based upon clear performance, not subjective properties of the people involved.

Therefore, as I stated in my prior post – and I apologize if I am misreading you – you appear to be looking for a way to justify discrimination based upon the properties of people, rather than basing judgements on the most neutral possible method – their performance.

“you appear to be looking for a way to justify discrimination”

Yup. That’s it, you got me. My dastardly plan of saying that hiring should look to see whether or not there are candidates that are or could be being missed by overly-restrictive requirements. What a clever tool to justify discrimination, by asking “are you sure there aren’t candidates that are being missed.”

Let me make it a ton simpler: believing that your objective criteria for determining that someone is the best candidate is without bias is the quickest way to look like an idiot. Biases hide everywhere: in politics, in science, in life. That’s why you *test* for them and determine if they need to be corrected.

You might have missed his now removed comment, he seems to have a problem with women in space, or maybe with women in general…

All in favor of ending censorship on the Hackadays say “aye”.

I’m in favor of Hackaday removing the censorship on my comments!

B^)

“If there’s a reasonable accommodation that makes person A’s performance equal to person B, it wasn’t the difference between person A and person B that’s the problem, the *job* is the problem, not the person.”

That’s a variant of property based judgement and therefore wrong.

The two applicants are objectively not equal – one of them will require the company to subsidize their needs, whereas others do not require this subsidy. Not only is that not fair to the other applicants who can do the job without the subsidy, but all the other prior employees who were hired do not get any bonus money equal to the subsidy.

Finally, trying to equate property based judgements with performance based judgements based upon the fact that an organization may be ignorant of all that is needed to be successful is a straw man argument. No successful organization accepts a body of unknowns and blindly goes forward. Instead, they reduce the unknowns to a manageable risk and focus on what they do know to drive success (e.g. the Apollo missions).

“I’m saying that you have to evaluate the *results* of the hiring process to evaluate the criteria you used. You can’t just point to the criteria alone. ”

If a company is hiring the wrong people or they have the wrong tasks defined for jobs, or the wrong objectives in general, that company will perform badly, and perhaps even fail if the problem is not corrected before it is too late. So, that is baked into the lifecycle of a company.

Well said, Sir.

Looks like Destin’s lecture to NASA at Smarter Everyday had an effect.

AVCOAT? Developed at Avco. I worked for A. C. Walker in their epoxy lab, summer of 1961, if I remember correctly. Secret stuff, but I found out later it was for the ablative heat shield.

Great reporting Tom. You have nailed the reasons for delay perfectly. NASA is bold in it’s vision of Artemis and the delays are for crew safety. Their reputation has been somewhat tarnished by the Space Shuttle program and they want to get things right. Bravo NASA. Bravo Tom.

btw… their federal budget for Artemis program is less than 10% of the Apollo program.

Another important difference between Artemis/Apollo is that Artemis is much more of a public/private partnership than a government program. Starship HLS, Blue Moon, Axiom Suit, and the CLPS landers are all fixed-price contracts and pretty much none of them cover the full price of the actual work – instead they’re basically being used as startup money and a lot of the additional costs are covered by the companies themselves.

Even STS is likely only cost-plus through Artemis IV and after that, if Boeing/Lockheed (after unwrapping corporate onion layers) can’t get the costs down they’ll go with other launch providers.

Artemis is really just the next generation of the CRS/COTS/CCTS/etc. programs which were extremely successful. Comparing it to Apollo completely misses the point.