Six years before Deepwater Horizon exploded in April 2010, the force of Hurricane Ivan blew an offshore drilling platform off its legs and into the Gulf of Mexico. For the last 14 years, that well’s pipes, long buried in mud and debris have been spilling oil into the Gulf every single day. That makes it the longest-running spill in history. Every day for fourteen years. Let that sink in for a bit.

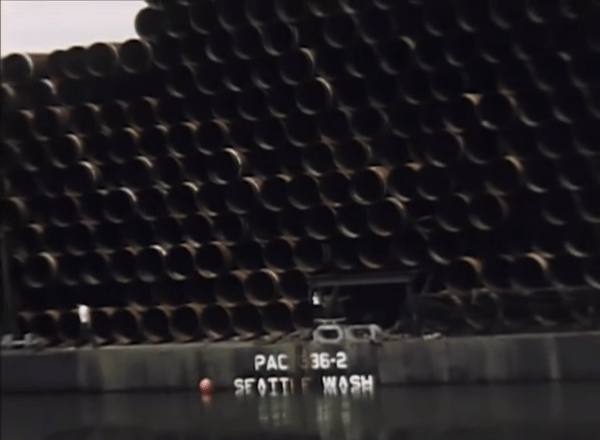

Taylor Energy’s platform sat just 10 miles off the coast, much closer to the Louisiana shore than Deepwater Horizon was. Since the hurricane hit, Taylor has tried a number of unsuccessful things to stop the spill. They’ve only been able to plug 9 of the 25 broken pipes so far. The rest are buried deep in mud and debris. Why on Earth haven’t you heard about this before? Taylor spent six years covering it up. And they might have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for pesky watchdog groups surveying the Gulf after Deepwater Horizon exploded.

So how are oil spills stopped, anyway? The answer depends on many things. Most immediately, the answer depends whether the spill happened onshore or offshore, and the inciting incident that caused the spill. Underwater oil spills are much more difficult to stop because of the weight and existence of the ocean. In Taylor Energy’s case, the muddy Gulf bed has become a murky tomb for the broken and buried pipes, which makes it even more messy.

Continue reading “The Murky Business Of Stopping Oil Spills”