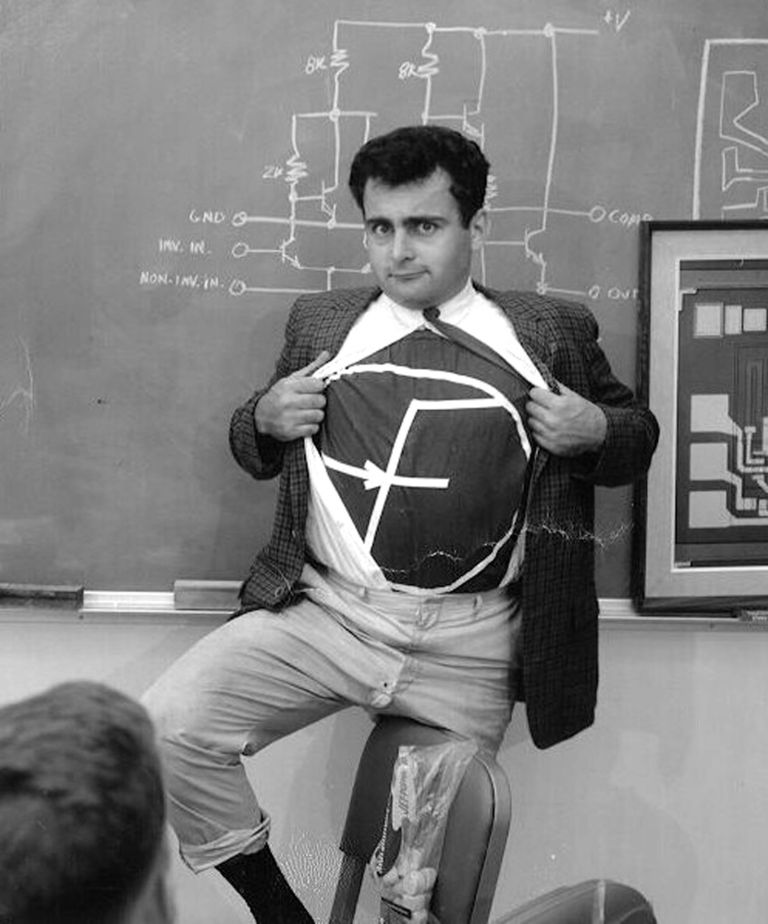

Bob Widlar (1937-1991) is without a doubt one of the most famous hardware engineers of all time. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that he is the person who single-handedly started the whole Analog IC Industry. Sure, it’s Robert Noyce and Jack Kilby who invented the concept of Integrated Circuits, but it’s Widlar’s genius and pragmatism that brought it to life. Though he was not first to realize the limitations of planar process and designing ICs like discrete circuits, he was the first one to provide an actual solution – µA702, the first linear IC Operational Amplifier. Combining his engineering genius, understanding of economic aspects of circuit design and awareness of medium and process limitations, he and Dave Talbert ruled the world of Analog ICs throughout the 60s and 70s. For a significant period of time, they were responsible more than 80 percent of all linear circuits made and sold in the entire world.

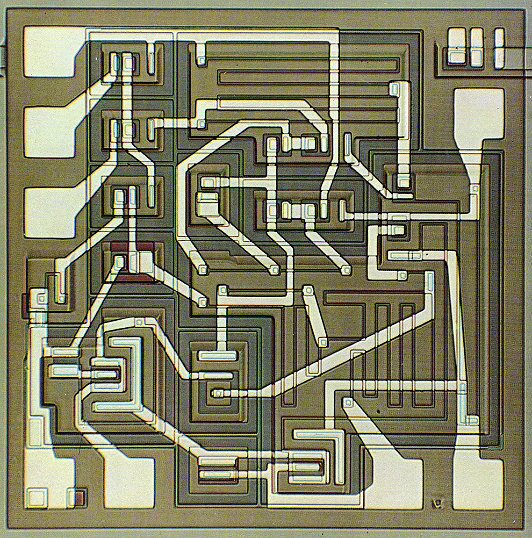

The list of his designs includes gems such as µA709, improvement over original µA702 and a Fairchild’s flagship product for years, µA723 — first integrated voltage regulator and LM10 — the first ultra-low-voltage opamp, which is still in production today. Students usually learn about Widlar via the textbook-classic: Widlar Current Source, a key piece in many of his designs, and the Bandgap Voltage Reference – both of which provide an infinite supply of mind-boggling exam problems. If there is one theme that’s common across all of Widlar’s designs, it’s that he has never designed an obvious circuit in his life. Every Widlar design comes with a twist, a unique idea and very often, a prank. A classic example of this is the story of LM109, the industry’s first three-terminal adjustable voltage regulator. In 1969, Widlar wrote a paper in which he argued against feasibility of monolithic voltage regulators due to temperature swings and packaging limitations. Since he was already an engineering legend by that time, the industry took it seriously and people gave up trying to pursue such devices. Then in 1970, he presented a circuit — LM109 — which used his bandgap voltage reference to achieve exactly such “impossible” functionality. It is most likely that he submitted both works within days from one another.

In addition to being a brilliant designer, Widlar was a personification of an age to come in Sillicon Valley, combining counter-cultural and in-your-face attitude with entrepreneurial passion and desire to build products that people love. He worked directly with customers and wrote his own app notes and data sheets. In fact, Widlar’s µA702 laid out the blueprint for how all analog IC data sheets are to be written in the future. His principle was “designing for minimum phone calls” and “if you make a million ICs; you get half a million phone calls if they don’t work right”. He was both destroyer of the worlds and creator of new markets; he came into Fairchild claiming that “what they do in analog is BS”, but left the company as a dominant player in linear IC for years to come, mostly on the wings of his designs. He then moved to Molectro (owned by National) but quickly ended up turning the parent company upside down and making into an Analog powerhouse. At the age of 33 he cashed out and retired in Mexico. But his hands couldn’t stay idle for too long. He soon came back as a contractor for National and, in 1980, ended up founding Linear Technology with Robert Swanson and Bob Dobkin,

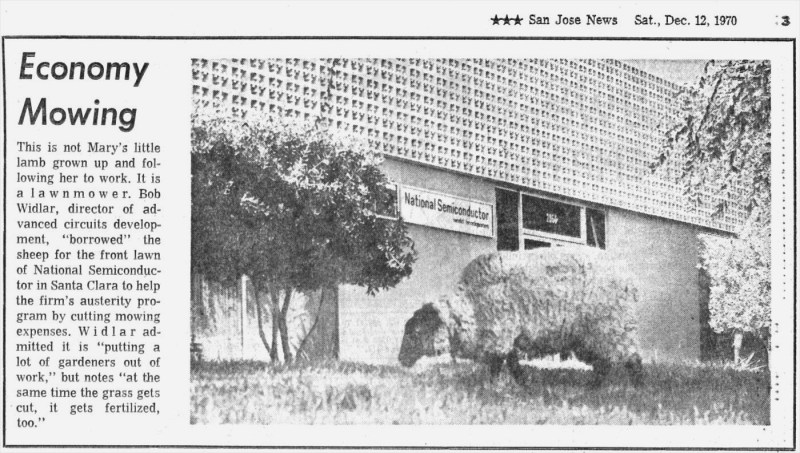

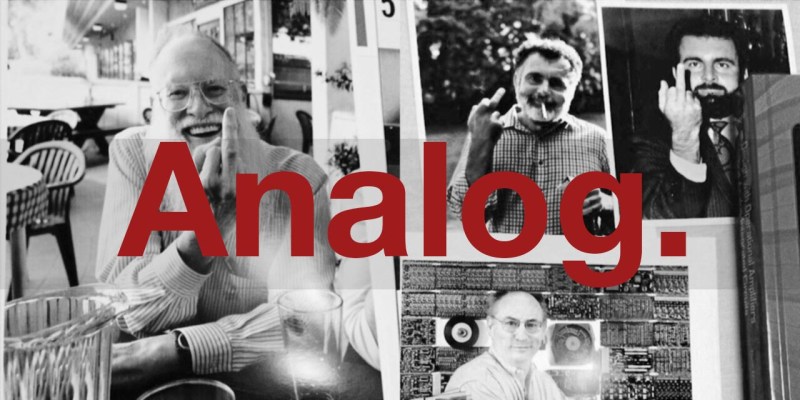

Still, he always remained a troublemaker, free thinker, and an HR nightmare… closer in spirit to someone like Hemingway than a fellow “professional” engineer. Such attitude was contagious and it inspired a whole new wave of “prankster” analog geniuses like Bob Pease and Jim Williams. Widlar’s pranks are too many to count and it’s really hard to pick one that captures the spirit of the times the best. Maybe it’s when Widlar brought sheep to the front of National as a reaction to the firm not mowing the lawns due to cost-cutting (he really just needed an excuse to annoy the upper management). Or when he cherry-bombed the intercom speaker, again, just to upset one of National’s Vice Presidents. Some of the pranks were actual hardware, like a “hassler” circuit he built to detect audio, convert it to a very high audio frequency and play back the converted sound. The net effect of such a design was that the louder someone talked in the office, the more annoying the “ringing” effect caused by the feedback was. As a person would stop shouting to hear what’s causing the ringing, the effect would disappear as well. This way, he managed to get everyone in the office into speaking quietly, Pavlov-style.

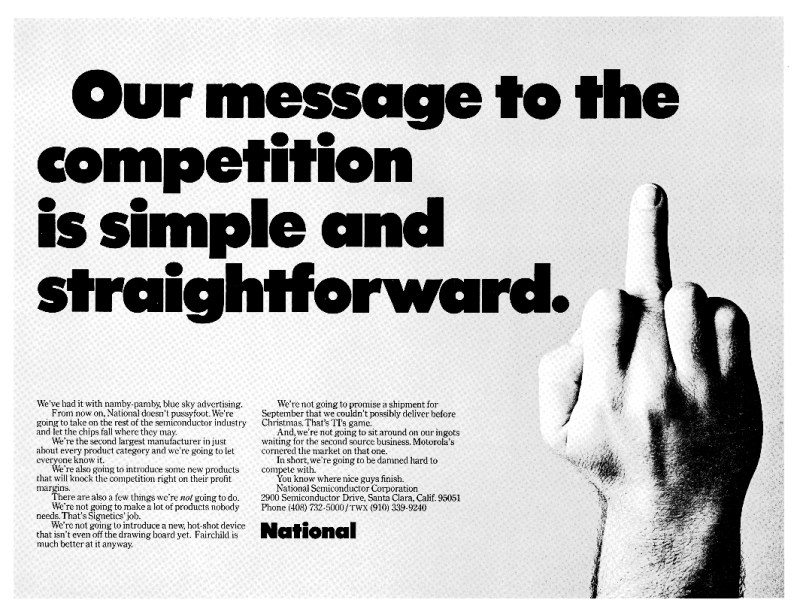

Widlar passed away in 1991 but his legacy lives on. He truly was the original hardware hacker and more than just an engineer – he was an Artist. It’s because of guys like him that Analog still has that special feel and is more about “invention” than just following the straightforward path between A and B. And that is why Analog guys still greet everyone else with a “Widlar Salute”.

Now, when I have finished my inspection, and I am still mad as hell because I have wasted a lot of time being fooled by a bad component – what do I do? I usually WIDLARIZE it, and it makes me feel a lot better. How do you WIDLARIZE something? You take it over to the anvil part of the vice, and you beat on it with a hammer, until it is all crunched down to tiny little pieces, so small that you don’t even have to sweep it off the floor. It makes you feel better. And you know that that component will never vex you again. That’s not a joke, because sometimes if you have a bad pot or a bad capacitor, and you just set it aside, a few months later you find it slipped back into your new circuit and is wasting your time again. When you WIDLARIZE something, that is not going to happen. And the late Bob Widlar is the guy who showed me how to do it.

Bob Pease – Troubleshooting Analog Circuits

References

[1] Bo Lojek – History of Semiconductor Engineering, Springer, 2007

[2] Bob Pease – Troubleshooting Analog Circuits, 1987

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Widlar

[4] http://readingjimwilliams.blogspot.com/2012/04/my-favorite-widlar-story.html

[5] http://analogfootsteps.blogspot.com/search/label/Bob%20Widlar

[6] http://electronicdesign.com/analog/what-s-all-widlar-stuff-anyhow

[7] http://silicongenesis.stanford.edu/transcripts/dobkinwilliams.htm

[8] http://edn.com/electronics-blogs/anablog/4311277/Bob-Widlar-cherry-bombs-the-intercom-speaker-item-2

Wonderful article. I got so much pleasure reading it in the office while I should work :). I lost 15 minutes of boring work thanks to you!

This article counts as professional development and should be added to your timesheet ;-)

Done, and approved, thanks!

Very nicely presented guys. Thanks. The last quote is now my new mantra for failed components….after the post mortem of course.

Great writeup!

Wonderful! I hope this is the first of a series.

He “revolutionized hardware” at a time when software was still a relatively abstract concept and basically every company was a hardware company.

Wow, Cave Johnson in real life.

+1 combustible lemon.

So i noticed that Bob Widlar is the man in the Transmission #2 Video. Picture identification here: http://imgur.com/a/5aQTA

funny that “we are not going to promise a shipment for September that we couldn’t possibly deliver before Christmas. That’s TI’s game” is still true today

the ironic part is that National is now a part of TI!

Why is it that the crappy companies buy the good companies and not the other way round? You’d think the latter would make more money.

Because the crappy companies tend to be the ones with money…

Yep. Part of being successful is knowing when being better isn’t…better. Very often “winning” in a given market is not about having the best product, but being the first to market with a “good enough” product, or the cheapest product over a certain quality bar. This is a huge part of what made Microsoft hugely successful while simultaneously being widely mocked by people who continue to buy and use MS products.

It is easier to build a house of straw.

All Hail Bob Widlar! Was Just reading the maverick genius’s wikipedia article yesterday!

Excellent story, great individual. Not one whose story is told all that much. You hear all about the folks who left Fairchild. Not so much about the ones who stayed. Hats off to Widlar.

Smart guy, the best ‘heavy drinker’ I know.

Anyone notice he resembles Andy Kaufman? Around the eyes and eyebrows…

I really like this kind of post, never heard of this guy before, great story!

I’ve heard of all Bob Widlar has made but I’ve never heard of him before. His death pursuing fitness is a cautionary tale indeed.

You’re not serious.

One of those brilliant people who deserve to be remembered forever and taken as an example by young techies and engineers. Thanks for the article, I really enjoyed it. Let’s hope the series continues.

Awesome!

I’m more of a digital type, so I wonder if there is also a genius enfant terrible in the digital revolution (lesser known than Steve Wozniak, I mean)

Behold…. The Widlarizer!!

http://www.eevblog.com/forum/chat/the-widlar-izer!/

Sweet. Where do you plug it in? ;-)

2 1b.; don’t real hardware persons use the 24 lb. version?

anyone else thinking sylvester mccoy… lol.

Yeah, that crossed my mind too. :)

Liked the article and wouldn’t complain if more like it where created. In a parking lot the other day a passenger in another vehicle gave the Widlar Salute, of course I returned it. Would that mean we both where analog guys?

He was a genius no doubt. He was also a legendary drinker. I met engineers who attended technical presentations where he was the guest speaker. You didn’t want to chance asking him a question. You’d be likely to get a response like “I’ve met fire hydrants smarter than you”.

he looks like Steve Carell

Haha @dbas, totally!!!

Let’s ask Adam McKey to make a film of that legend.

Based on what I heard from someone at NSC at the time, the NSC ad with the middle finger was done by Mike Scott (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Scott_%28Apple%29) who went on to be Apple’s first president.

Lest it be forgotten, back then they’d NOT had a fraction of the resources we tend to take for granted. It was not enough to design a “working” circuit- it had to be Producible, Stable- and Financially Viable. Three often decidedly antagonistic areas in many processes.

There was no FEA modelling either…

I wonder how much of a chance in hell even the most gifted “Average Hackers” would have of getting any functional IC processes into production with the resources Widlar had?

Don’t forget, back then- some of the processes were make up as you went along too.

That “hassler” curcuit seems interesting, anyone has some info about it?

Digital? Every idiot can count to 1.

Very enjoyable article — thanks for writing it. Wish I had seen this sooner! Widlar was one of a kind, the likes of which we are unlikely to see again in our business.

One minor nit: I doubt that he designed the 723, and I’m wondering where you found that claim. At best, perhaps he sketched out some rough ideas before he left Fairchild, but the part wasn’t introduced until well after Widlar had joined National. Plus, the part doesn’t contain the idiosyncracies that you normally see in a Widlar chip. If he had anything at all to do with it, it must have been in the earliest phases of design, and someone else actually did the work.

After doing a bit more research, I found that the actual designer of the 723 was J.D. “Darryl” Lieux (he went by his middle name), according to Dave Fullagar — father of the 741 and Lieux’s coworker at Fairchild at the time.

Lieux passed away just last year. We should honor his memory by giving him the credit he’s due.

So if you Muntz a project, should you Widlarize what you’ve taken out just to be safe?

An aphorism from those days, though a little off topic: once you had blown up components to the value of your salary for the day, it was time to go home.