Newly minted hams like me generally find themselves asking, “What now?” after getting their tickets. Amateur radio has a lot of different sub-disciplines, ranging from volunteering for public service gigs to contesting, the closest thing the hobby has to a full-contact sport. But as I explore my options in the world of ham radio, I keep coming back to the one discipline that seems like the purest technical expression of the art and science of radio communication – low-power operation, or what’s known to hams as QRP. With QRP you can literally talk with someone across the planet on less power than it takes to run a night-light using a radio you built in an Altoids tin. Now that’s a challenge I can sink my teeth into.

Why QRP?

QRP takes its name from the Q-codes developed as shorthand by early Morse operators. QRP mean “Reduce power” or when posed as a question, “Shall I reduce power?” It has gradually morphed into a catch-all term that describes the whole field of low-power operation. Not surprisingly, there’s no hard and fast rule as to what constitutes QRP, but like a lot of things in life, you know it when you see it. Generally, any radio capable of transmitting at 5 watts or less would be considered a QRP rig, although some argue for anything below 10 watts. In the end these limits are academic, because most QRP aficionados like to work with much lower power, typically only a watt or two. Extreme QRP, called QRPp, lives below a watt and sometimes is best measured in milliwatts; for some serious over-achievers, it’s even measured in microwatts.

Why would anyone bother with handicapping themselves with such low power from the outset? Most commercially available rigs, like the Icom IC-7200 sitting in my shack, are capable of putting out 100 watts, and with even a marginal antenna I can make contacts around the world without much effort. If I wanted to I could attach a linear amplifier and start blasting out a kilowatt or more. But amateur radio operators in the USA are required by the FCC to “use the minimum transmitter power necessary to carry out the desired communications” (CFR§97.313(a)). So technically, if your rig is dialed up to 100 watts but you’re operating under conditions where 5 watts would do, you’re breaking the law. More importantly, though, it’s not good operating practice, and it contributes to QRM, or man-made interference. With the ever-narrowing slivers of spectrum allocated to amateurs getting more and more crowded, it’s just not very neighborly. Learning how to make a contact with the power turned way down is a great tool to have in your arsenal.

But underneath the neighborliness and good spectrum hygiene, there’s an even better reason to make QRP contacts: because you can. Anyone can get their license, spend some dough on a transceiver, string a simple dipole antenna up in some trees and start yapping away at 100 watts. But a QRPer who can make the same contact using a twentieth of that power, and do so with a pocket-sized radio powered by a 9-volt battery? That shows skill and a deep understanding of radio. I think that’s the attraction for me.

QRP Gear

Most commercially available high-frequency (HF) transceivers are capable of being dialed back to QRP power levels, so chances are pretty good that most hams already have the gear needed to work QRP. And there are dedicated QRP rigs out there as well – Elecraft makes some sweet QRP radios with all the bells and whistles. But part of the allure of QRP is building your radio, and that’s what really fascinates me about the field. I’ve always had a pretty good handle on digital electronics, but analog circuits always seemed harder to grok. And RF circuits are just the stuff of wizards and demigods in my book. I want to change that, and I think being able to build my own transmitter would be a real hoot, and being able to understand the circuit at a really deep, fundamental level would be a game-changer for me.

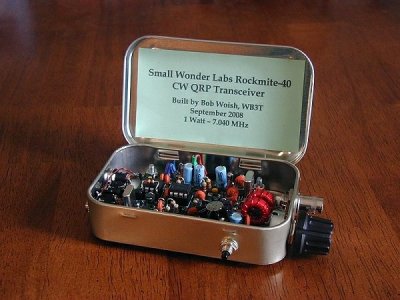

With that in mind, where does one start with a homebrew QRP project? Unsurprisingly, the internet is chock full of plans and kits for everything from full-featured QRP rigs that can work single-sideband (SSB) and continuous wave (CW) modes to tiny CW-only transmitters that fit in an Altoids tin or even an old tuna can. If you get adventurous, you might even try building a QRP rig out of the guts of a cast-off CFL lamp.

The Altoids tin builds are a special sub-specialty of QRP – packable radios. With a pocket-sized radio, a few batteries, and a coil of wire for an antenna thrown into a backpack, you can communicate with the world from anywhere your feet can take you. This can prove handy, as it did for a young QRPer canoeing in Canada who wanted to reach his girlfriend in Ohio. Out of cell range but equipped with a 5 watt QRP rig, he made contact with a ham in Germany who sent an email to the young lady to let her know her boyfriend was alright and thinking of her. A roundabout route for sure, but QRP skills can be practical as well as fun.

One thing you’ll notice when you’re shopping for a QRP rig is the prevalence of CW-only transceivers. Continuous wave is the simplest mode of radio communication, using a radio signal of constant amplitude and frequency that’s either on or off. CW radios are simple to build and simple to run, and being a very low-bandwidth mode, CW is often able to punch through where more complex modes can’t, a decided advantage when you’re working QRP. The downside: you’ve got to learn Morse. That’s on my personal life list of skills, and when you think about it, how hard can it be to memorize about 40 symbols? Considering the doors it opens up, it’s a worthy investment.

Records are made to be broken

So just what’s possible with QRP? Are you going to be stuck making contacts across town? Or can you really reach out and touch someone across the planet? We’ve already seen that a Canada to Germany contact with 5 watts is possible, but how far can we stretch the limits of power and distance? As it turns out, pretty far. The current QRP miles per watt record is 1,650 miles from Oregon to Alaska on the 10-meter band using 1 microwatt! That’s the equivalent of 1.6 billion miles per watt. To put that feat into perspective, Pioneer 10 achieved “only” 850 million miles per watt before the space probe finally died in 2003, and it took a ground antenna that might not please the neighbors to pull that off. A little less extreme is the copying of a 40 microwatt CW beacon run by the North American QRP CW Club at 546 miles, or 13.5 million miles per watt. Just recently, the first solid-state rig to make a transatlantic contact entered the ARRL museum collection. The two-transistor radio sported 78 milliwatts on the 20-meter band; at a mere 47,500 miles per watt, it’s a more typical example of what QRPers accomplish every day.

Extreme examples aside, contacts of thousands of miles on just a few watts are happening all the time as hams push their rigs and their skills to the limit. You don’t have to shoot for a record to enjoy QRP – just set your sights low and give it a try.

Best I ever did was Colorado to Germany at 1W on 10 meters when I was operating a propagation beacon.

QRP is extremely attractive because of the price.

Go price out an Icom IC-7200, then price out a Rockmite kit….

Also WSPRS is a great tool for seeing band openings with a digital QRP setup, or just going to the website and looking at the map…

second that jon I cant afford my radio. Im building a az el rotor system but am gonna end up giving it away when done because i cant afford the radio for iss contacts.

I have seen multiple people contact the ISS using moderate gain antennas that were homemade and one of the Boefong $40 handhelds.

A 400-470 Mhz handie-talkie from BAOFENG is $20 (USD) at wish.com (China) – I also found a UHF yagi-uda around 460 (???) in a vacant building (would need tweaking). If I build a cheapy az-el out of two old TV rotors I could plausibly uplink to ARISS at 437.80 and listen on a separate radio at 145.80 MHz. Doppler shift will cause the ISS transmit frequency of 145.800 MHz to look as if it is 3.5 kHz higher in frequency, 145.8035, when ISS is approaching your location. During the 10 minute pass the frequency will move lower shifting a total of 7 kHz down to 145.7965 as the ISS goes out of range. To get maximum signal you ideally need a radio that tunes in 1 kHz or smaller steps to follow the shift but in practice acceptable results are obtained with the radio left on 145.800 MHz.

In a vacant building huh? Sounds like a score! Maybe it was used by spies… B^)

Ren – You know I was wondering the same thing. It appears to be set for FRS or GMRS UHF band. It’s a big (long) sucker too for a UHF yagi. It must be high-gain. I found it in a urban neighborhood where it’s not to wise to hang out at night on the corner counting money. (LOL) Maybe some LEOs left it behind after some sort of op. Or some GMRS op. Finders keepers right? It appeared abandoned to me but in perfect shape! I’ve had it for years with the DIY az-el already mounted. If I bring it outside I will get strange looks from my nosy neighbors (“What the hell is that tin-foil-hat guy doing now?”) :-P

sweet thanks I hadn’t gotten that far.

If you have a smartphone (Android) you can track ISS position: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.runar.issdetector&hl=en

https://youtu.be/CjS7tT44YcY

When (if?) I retire, I want to spend some time in Billings County, North Dakota, and work QRP, and see if I can Work All States! WAS)

Love that idea! I’m brushing up on my cw skills and am going to start my all states hunt too (i am retired so no excuses).

From North Dakota, it shouldn’t be too hard, especially if you announce that you’ll be making the attempt, and if you keep a fairly regular schedule. Because of its low population, North Dakota is a somewhat rare state, and there are plenty of operators around the country who will be eager to make contact. You’ll probably help a few other hams complete their Worked All States (WAS) award in the process of getting your own.

never been a fan of contesting , or rag chewing. My purpose for my ham license is primarily to enable me to legally run my fpv equipment. The secondary use is experimentation. The final use case is emergency coms. I like our local lunch net and astronomy net but aside from that I rarely ever key up.

If you don’t like RAG CHEWING, design a Natural-Voice TTS user interface with free form and canned things to say. You could use the VOX on the xmtr or write it in VB and send a bit to the serial or parallel port to fire a PTT relay for the rig. This would be great for people with verbal challenges like Dr. Hawking. And if your patient you might get a VR program to decode the loudspeaker output to text. This should be easy for Windows.

Were I ever reenter the hobby this would be the only area that could hold my interest, particularly QRP digital modes.

I remembered a transmitter made out of a PC clock crystal called the Fireball transmitter, found the link to an article in the Noember 1990 issue of 73 Magazine (starts on page 18)

https://ia700805.us.archive.org/8/items/73-magazine-1990-11/11_November_1990.pdf

I was fascinated by the fact that the whole transmitter was made out of 3 components, a relay, a 1k potentiometer, and the clock crystal and that you could fit them into your shirt pocket. As I recall there was a whole ‘club’ organized around these transmitters, based on just how low power and how far you were able to verify transmitting…

This is WA6YPE (Bill). Myself an Bob K7IRK started the whole Fireball Transmitting Society when we were making our 2 year long world record QRP ARCI Miles Per Watt attempts between Palestine TX and Glendora CA 1343 miles. We finally got down to 6 micro watts so that made 128,333,333 Miles per watt with a postage stamp sized transmitter. I’m sure the record has been bettered by now. Love 10 meters. Still active on QRP but with a new challenge. Indoor magnetic loop antenna only. Kinda like bear hunting with a switch.

Hello Bill WA6YPE, Bob K7IRK here. You may recall that later, on 1-19-1992 we got down BELOW 1 microwatt to .72 microwatt. WB8ELK was on that night and copied the signal as well. WB8ELK was in Findlay, Ohio a distance of 1,536 miles from Palestine, Texas. That’s 2.133 BILLION miles per watt! Still the record today (5-17-2021) I believe. What fun we had back then! de Bob K7IRK

I made a tuna can rig back in 2010. http://resfree.org/2010/09/12/bumble-bee-transceiver-experiment/

Now eBay seems flooded now with 40 meter crystal rigs like it, but in the Extra class spectrum instead of the international QRP calling freq of 7.030 MHz. For EmComm use it would be nice to have Technician (entry ham radio class) spectrum devices that don’t require the user to know Morse, https://synshop.org/blog/permakent/what-i-plan-do

On the 80m, 40m, and 15m bands, technicians only have access to the Morse Code portion. In theory, it’s possible to have a computer generate the Morse code, and have a computer decode it at the other end. But in practice, machine decoding of Morse only works well if the two stations are VERY close, with lots of power on a clear channel. Machine sending of Morse is very easy, of course.

There are other modes that are designed for machine decoding, which work well. The PSK modes and JT modes come to mind. They’re not available to technicians on HF, but I’d say it’s much easier to upgrade a license to a general class than to get machine decoding of Morse working reliably. Alternatively, it’s also a lot easier to learn to decode Morse by ear than it is to get a machine to do it reliably. I speak as someone who has tried all of these strategies.

My first QSL’ed Morse contact was when I had a radio and computer system that could send and receive Morse code, but I didn’t know how to copy Morse by ear. I had already played with PSK31 with good luck, so I thought I’d try Morse. I called CQ, and got an answer from a guy a thousand miles away, with a bit of typical fading and static. I actually did copy the other guy’s call sign, but not a single other thing. He was sending a lot of things to me, but all I could do was say, “sorry, I can’t understand”. Oops, I’m still embarrassed and sorry about that. That disaster motivated me to learn Morse by ear, and I’m now confidently using it at least a few times a week at 15-18 WPM.

I vaguely recall a QRP transmitter that was powered by the action of CW keying mechanism only but I haven’t seen mention of it since.

There’s this: http://hackaday.com/2013/11/26/amateur-radio-transmits-1000-miles-on-voice-power/

You mean like this 10M beacon I made years ago?

http://hoffswell.com/n9ssa/beacon.html

I like the idea of using a beacon configuration for QRP work and some sort of CA (computer assisted) mode like MINIMUF and other programs for Hams. I would also like to see folks like HaD use Virtual Ham Radio using a voip connection that is designed to SOUND and act like real Ham radio (i.e. fading, QRM, etc.) but no license needed. That would be HAMSPHERE ( http://www.hamsphere.com/ ). Somebody at HaD should set up a routine voice conference on this venue. One version is free and you get your own callsign Available on smartphones too…

https://youtu.be/zJNWSmsXjEU

Dang! I thought my personal record of 4600 miles/Watt was pretty good (central NH, USA to Perth, AU at 2.5W on 20m). I guess it wasn’t as good as I thought. Oh, well. It was fun anyway. I wasn’t out to set records.

DainBramage – I’m not sure but with a Windows program called MINIMUF and access to a database record of sun spot cycles you can pretty much “call your shot” (billiard metaphor). I once saw it is QST mag. Never tried it though. There are many evolutions of it – I think some have automatic updates of SSN’s too.

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=sv1djg.hamradio.apps.propagation.mufpredictor&hl=en

Personally I feel that only two way contacts that exchange information could count as record setting event. In the event one recognizes telemetry from a space probe,one should also recognize the possible record set by TV signals that made a nearly a 50 light year round trip. http://www.rimmell.com/bbc/news.htm . I may play at QRP in the future, but first I want to restore Morse code skills lost because of a bad brain injury.

You are supposed to wait around 3.5 weeks before you bring up that link again…

Getting a QSL card IS a “two way contact” B^)

Did you notice the date of publication on that article?

LOL. I didn’t even look at the link to see BBC in it. I started to read the article… thought wouldn’t it be cool if they received and recorded some lost episodes of old shows… Dr Who in particular came to mind. Kept reading.. saw the Dr. Who reference… Thought no way… better check the date… Confirmed the date was what I expected.

Hard core Radio Direction Finding just might be the closest thing to full contact sport ham radio has to offer. While marginally related to QRP the 14er event in Colorado is a ham radio extreme sport. That is for those activating the peaks, not those in the Kansas flat lands setting in the shack.

Back in Colorado, my dentist and his college buddy were the first to ascend the 54 14ers in 54 days…

In his Waiting Room was a photo of him flossing his teeth on the face of cliff. B^)

WG0AT is my favorite SOTA participant, cause goats! He has a YouTube channel and does homebrew.

I once read that if one were to fly a kite with a wire attached (not during stormy wx of course!) to a telegraph key which is grounded that it will be a QRP transmitter. Frequency is determined by the length of the wire.

Years ago on USENET, I enjoyed reading Ed Hare discussing a QRP exchange with another ham.

Finally, he hooked up to a dummy load, and the guy at the other end claimed to receive his transmission!

(Ed was literally rolling on the floor laughing when he heard that response!)

Gotta mention QRPI http://rfsparkling.com/qrpi/

Funny, I’m writing an article on that just this very minute…

some of peter parkers rigs are well worth a look. vk3ye on youtube.

generally Hams don’t count it as a contact unless information (normally at least callsigns and signal report) is exchanged.

I (vu2zap) have a contact with W3LPL more than a decade ago on 10M with 1 milliwatt. 2W fed to a 33 db Narda power attenuator. QRPpp is fun!

Not a ham, just an engineer- doesn’t non-directional radiated power scale as an inverse square? When you say “1,650 miles using 1 microwatt! That’s the equivalent of 1.6 billion miles per watt.”… is it? If you can contact 1650 miles on one microwatt I’d have thought you’d get 1,650,000 miles out of one watt.

If the power is reflected and contained between the Earth’s surface and its ionosphere, the power density doesn’t scale with inverse square of distance, because it’s not expanding evenly through a 3-d volume. To show that, consider that there’s a point of maximum power right at the point on earth antipodal (opposite) to the transmitter. For illustration, a transmitter at the North Pole using an omnidirectional antenna would be received reasonably well by a transmitter at the South Pole using an omnidirectional antenna, as signals leaving the transmitter in any direction would follow the lines of longitude and converge on the receiver. That works not only for transmitters/receivers on the poles, but on any two locations at exactly opposite points on Earth. And even if the points aren’t quite opposite, the power density still doesn’t scale exactly as the inverse square of distance.

Accurately modeling the true received power is complex, because reflection off the ionosphere (and off the surface) is incomplete, with losses.

But yeah, on the major point, you’re right. Though the power doesn’t exactly scale with inverse square of distance when you consider ionospheric reflection, it’s also true that it doesn’t scale with the inverse of distance, so it’s not fair to say that 1,650 miles with one microwatt is equivalent of 1.6 billion miles per watt. The “miles per watt” ratio isn’t so meaningful. It is, however, easy to compute. That’s probably why it’s quoted so often in QRP circles.

Worked an Italian QRP station claiming 500 milliwatts on 15 during thr ARRL SSB DX contest. He was a good 5X5 but got the traditional 5X9 contest report.

http://soldersmoke.blogspot.co.uk/2016/01/qst-de-aa1tj-please-listen-for-mikes.html

Some of us have to run QRP due to neighbours or antenna or height limits.

but still a challenge to overcome, or an antenna to hide.

My first ever cw contact was with a guy who was using a home brew 500 mW TX. Distance about 110 miles, line of sight. The icing on the cake was when he told me he was 90 years old!

That’s great! I played around with this years ago. Here’s my 10M beacon! I’m the guy that wrote the miles-per-watt calculator that many QRP’ers use.

If you like QRP ham radios then you will definitely be interested in the KeychainQRP HF transmitter. It’s so tiny you can keep it attached to your car keys and hardly notice it. They are still available on Etsy.

Here is the link: https://www.etsy.com/listing/506756455/keychain-qrp-the-worlds-smallest-hf-ham

Around the year 2000 when 10M was the best in my lifetime, w3lpl was pinning my meter here in S India hard! I suggested QRP and both lowered power to minimum and was still 9++. I then connected a 33db Narda attenuator to a measured 2W out from the rig and got a 1mw out. I could hear him Q5, he gave me a 3/3 and the credit goes to his antenna farm! My antenna was a 4el beam. Since then I have worked with 100mW all over Europe on 10M and even Easter islands on 6M.

Newly retired, I find learning ham radio is a practical and fascinating pastime for expats like me who have settled far from our birth countries and have less than perfect language skills with the local residents. Learning old radio is even more so, which is perhaps a large part of the fun for retirees who still remember the electronics from our school days but need help (read “internet”) with the newer digital stuff. We can also see the dang circuits without having to use a microscope, and the fun of making at least some of our own components is the same fun my great-grandfather had when he built his first transmitter in 1908 giving him membership in the Old Old Timers’ Club (I still have the certificate). His daughter received a marriage proposal from New Zealand to New York in 1926 over his newest rig, which he’d by then updated to a few watts of power with a homemade pentode TX circuit (she accepted, by the way). Where I live I don’t have access to clubs and elmers and hackerspaces and lots of equipment so this is in all aspects a deeply personal project for me. And the joy of restoring old equipment to like new condition is its own reward, especially the old tube rigs, as antique radio has a unique and fascinating history the digital age simply doesn’t have. It would be a great waste if we were to leave those fine old radios to die idle and unpowered in museums or collect dust and rodents in old garages for the rest of time.

For those wanting to work all states, there’s the triple h Net

it’s a worked all states and dx net. hhhnet.net

Just stumbled on to this site. I love it when the bands cooperate. If not, try again. AL7FSZL1MH – 1,549,111 miles per watt

Random QSO: AL7FS answered ZL1MH CQ QRP.

This 2xQRPp QSO was between AL7FS, Jim Larsen and ZL1MH, Mike Hutchins.

Anchorage, Alaska to Waima, New Zealand, about 29km west of Kaikohe (Kaikohe is about 250km north of Auckland)

Date: 8/19/2000 at 0642Z on 14.060 MHz

ZL1MH at 100 mW received a 559 from AL7FS

69,710 miles per watt at a distance of 6.971 miles

AL7FS at 4.5 mW received a 229 from ZL1MH

1,549,111 miles per watt at a distance of 6,971 miles

(Calculated using the QRP-L Server calculator function)

AL7FS details:

…Kenwood TS450S, OHR WM-2 QRP wattmeter, KLM KT34A at 40 feet

…Latitude: 61.1009636 N – 61 degrees, 06 minutes, 03 seconds N

…Longitude: 140.82379 W – 149 degrees, 49 minutes, 26 seconds W

ZL1MH details:

…Elecraft K2, wattmeter unknown, antenna is a BIG horizontal loop, around 1200ft long, 50ft high and fed with openwire line in the south corner (loop is square). Uses z-matchATUs and uses the loop on 160 through 10m. Been using it for 13 years, noproblems and not much maintenance!

Jim, AL7FS, Anchorage Alaska