If you were to nominate a technology from the 19th century that most defined it and which had the greatest effect in shaping it, you might well settle upon the railway. Over the century what had started as horse-drawn mining tramways evolved into a global network of high-speed transport that meant travel times to almost anywhere in the world on land shrank from months or weeks to days or hours.

For Brits, by the end of the century a comprehensive network connected almost all but the very smallest towns and villages. There had been many railway companies formed over the years to build railways of all sizes, but these had largely conglomerated into a series of competing companies with a regional focus. Each one had its own main line, all of which radiated out from London to the regions like the spokes of a wheel.

By the 1890s there was only one large and ambitious railway company left that had not built a London main line. The Great Central Railway’s heartlands lay in the North Midlands and the North of England, yet had never extended southwards. In the 1890s they launched their ambitious scheme to build their London connection, an entirely new line from their existing Nottingham station to a new terminus at Marylebone, in London.

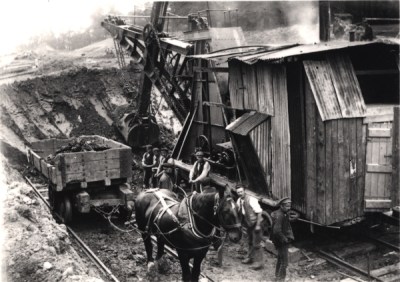

Since this was the last of the great British main lines, and built many decades after its rivals, it saw the benefit of the century’s technological advancement. Gone were the thousands of navvies (construction workers, from “Navigational”) digging and moving soil and rock by hand, and in their place the excavation was performed using the latest steam shovels. The latest standards were used in its design, too, with shallow curves and gradients, no level crossings, and a wider Continental loading gauge in anticipation of a future channel tunnel to France This was a high-speed railway built sixty years before modern high-speed trains, and nearly ninety years before the Channel Tunnel was opened.

We are fortunate in our ability to see the construction of the line at first hand, because a professional photographer and railway enthusiast recorded every aspect of its construction. S.W.A. Newton traveled the length of the emerging line with his camera, and his archive gives us a fascinating glimpse of the cutting edge of 1890s civil engineering practice in operation as well as a cross-section of everyday life in late Victorian England. We see details of the substantial brickwork and riveted girders that carried the new line over existing roads and railways, we see impressive earthworks built up by endless contractors’ tipping trains on temporary track, and there are plenty of pictures of the Ruston steam shovels at work. Alongside this demonstration of 19th-century civil engineering might, we find horse-drawn wagons, pictures of the rural hamlets and villages surrounding the line, and the temporary camps that housed the navvies and their families.

The Newton Great Central collection appears in several places online, as well as the Leicestershire County Council site linked above there is another resource that allows you to tie photographs to modern maps and buy prints. It’s quite possible that many readers could spend a lot of time browsing this world of another century’s railway construction.

The Great Central London Extension was a modest success, but it never successfully tackled its fundamental problem of not passing through any major population centres south of its Midlands heartland. Small market towns like Brackley gained mainline stations, but there was nowhere of significance that relied upon it. As the railway companies were amalgamated in the 1920s it became an insignificant part of the much larger London and North Eastern Railway, and when the railways were nationalised after World War Two it entered a period of decline. It was eventually closed in the Beeching rationalisation of the system in the 1960s, and today only the southern section into Marylebone survives as a London commuter line and a short section at Loughborough as a preserved steam railway. If you are a Top Gear fan you may have seen Clarkson and cohort towing caravans along it a few years ago. The rest of the line remains derelict or has been obliterated by more recent development. Meanwhile the foresight of the original design in creating a high speed railway has surfaced again in the 21st century, as a substantial section of its route is to be followed by the planned HS2 200mph+ high speed railway.

Header image, 70013 “Oliver Cromwell” leaving Quorn on the preserved section of the Great Central. Paul Lucas (CC BY 2.0), via Flickr.

Bring back rail!

After being sick with a virus all this week with 6 total hours of sleep and days of continuous violent coughing with breaks lasting less than 5 minutes, I want all air travelers and airports gone from the face of the planet. If going that way you will have to check into 2 to 4 weeks quarantine and wear a moon suit to board a plane that crosses an ocean then the same long stay at the other end. Close the filthy common raising of ducks and hogs in China and elsewhere. Birds spread their cross breed germs around the world.

My only train trip was to Chicago to take in the city and then a rail ride to Ohare for the first Midwest Personal Computer Convention in ’78. $13 round trip.

I think that is adult human –> baby –> dog –> pig –> duck –> carp –> adult. Where would we get the flu without it? Helluva virus incubator, with short UV from the Sun added for spice.

From my couple of years working at the Great Central Railway (as in this article) I got to appreciate just how filthy coal fired engines are. Every time you wash your hands on shift the water comes off Black, like really Black. every surface when wiped even on the inside of the trains came up dark and grubby. (in high – hygiene areas) the coal dust gets everywhere and cannot be seen in the air.

while this doesn’t address germs etc. going back to coal fired engines would be a very definite step back in terms of cleanliness, air quality (remember the smogs) and efficiency.

If any of you guys are in the area (leisctershire) it is worth checking out the railway (loughborough station), especially on their war weekend event (june/july), it’ll say on gcrailway.co.uk.

“If the Almighty were to rebuild the world and asked me for advice, I would have English Channels round every country. And the atmosphere would be such that anything which attempted to fly would be set on fire.” — Winston Churchill

Amazing article, thanks!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4hUFzAcQ3uA

HS2 only follows it’s route as far north as Brackley, not very substantial….

The Great Central Railway is not entirely defunct! Not only does the main line from Aylesbury (my home town) to London Marylebone run along the GCR route, it is in the process of being opened up to the north to join up with the reinstated Oxford to Cambridge ‘Varsity Line’.

For further reading I suggest Railways and Rural Life by Gary Boyd-Hope and Andrew Sargent which contains many pictures of the construction.

Funnily enough you aren’t the only one to hail from this part of the world :)

I do mention the London end above, i.e. the commuter line to Aylesbury. And of course the Princes Risborough – High Wycombe route too.

“If you were to nominate a technology from the 19th century that most defined it and which had the greatest effect in shaping it, you might well settle upon the railway.”

Uhh, I was thinking more like nominating the “steam engine” as a technology. The railway is more of an application. It used steam engines, but they were also used in factories, mines, construction equipment, powerplants, and farming and drove the industrial revolution.

On the other hand, from a “system approach”, the railway was also an early adopter of the telegraph, and of organizational theory. Also spurred the concept of time zones.

^^^ This, the steam engine was only a small part of the industrial revolution. So much other stuff went around it in terms of engineering, organisation, communications, etc. that made it a revolution.

I remember my first COAL POWERED train ride was (with a Direct Drive Transmission) at the Cass, West Virginia Railroad. The train was the Shay #5. It went up the hill in a “Zig-Zag” fashion. I have also rode trains in Great Britain from Slade Green in Count Kent to Arsenal, Waterloo, etc. Taken a 4 hour ride to Glasgow, Scotland. Ridden trains in Germany from all the way in Donauwoerth, Germany down to Bad Hofgastein, Austria. I can’t wait to take my family on either a cross country train ride here in the US, or European Rail all around. If you have the infrastructure, trains are the way to go.

The continental loading gauge thing is a myth that has ended up getting very widely reported. As built, the Great Central was not capable of taking modern European rolling stock as we understand it today – it opened fourteen years before the standards for them were agreed. At the very best it was built to generous standards for the UK, but would have needed a lot of work to take full-size European rolling stock. A bridge near Charwelton was apparently constantly struck by steam loco tenders, so no, it was absolutely not big enough to take Continental trains.