Last time in Life on Contract, I discussed ways to figure out a starting point on how much to charge for your services. However, sometimes you and a client may wish to work together but for some reason they cannot (or do not wish to) pay what you have decided to charge. If you are inexperienced, it can be tempting to assume you have overpriced yourself and discount down to what they are willing to pay. But if your price is a number you have chosen for reasons you can explain, dropping it is not something you should do unless you have thought about it carefully.

Instead of just agreeing to do the same work but for less money, it is often possible to offer a lower overall cost without cheapening the value of your work. I’ll share a process I use to find opportunities to make this happen.

It Should be Win-Win, Not Hard Sell

The best case scenario is a client wants your service, your cost is within their budget, and everyone agrees to work together. Tragically, the process isn’t always that smooth. If cost is an issue, the alternative to lowering your price is to fine-tune what you provide to better fit the actual needs. To do that, you will need two things:

The best case scenario is a client wants your service, your cost is within their budget, and everyone agrees to work together. Tragically, the process isn’t always that smooth. If cost is an issue, the alternative to lowering your price is to fine-tune what you provide to better fit the actual needs. To do that, you will need two things:

- A detailed understanding of your own time and costs for the work.

- Knowledge of what things your client considers most important.

By intimately knowing your own costs, you can figure out where to make savings without scrimping on the things your client considers important.

For example, if low cost is most important to your client, it would be reasonable to offer a lower price in exchange for the client taking on some of the “grunt work” like assembly, post-processing, finishing, and so forth. If you have ever purchased a product in kit form instead of fully assembled in order to save some money, than you already know what I’m talking about. In effect, as the service provider you accept less money from the client, but keep more of your own money or time in return.

How to Understand Your Time and Costs

In principle this is simple: record where your time goes, where money gets spent, and how much of each is used to create your product or perform a service. The details don’t need to be utterly complete. You only need enough to use as a basis for some reasonable decisions, and that is a very accessible goal.

If you know where your top three biggest time and money sinks are, you can focus your attention on those and not sweat the smaller stuff. To figure them out, use one of the following methods.

Do You Produce Things?

An accurate Bill of Materials is a good start, but doesn’t capture the time or costs involved in the process of turning parts into things. Breaking a product or service down into components, capturing the cost of those elements, and accounting for hidden costs is what will give an understanding of how much time and money actually goes into creating something. The math is simple; it’s more about capturing the right data.

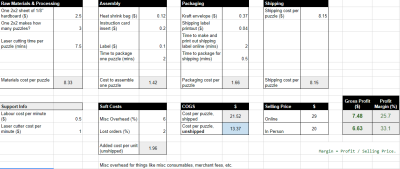

Most Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) calculators don’t serve the needs of an individual very well, so I created a spreadsheet available on GitHub that shows how to break down a simple product to see how time and money are distributed across manufacturing, assembly, packaging, and shipping. I use a copy of it for my own projects and work, and I happen to think it’s pretty generally useful.

Do You Provide a Service?

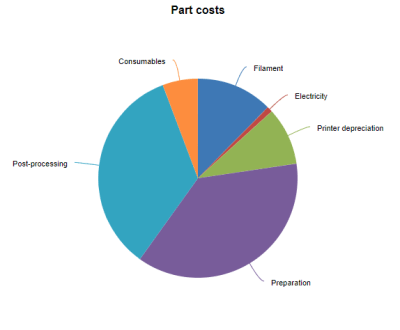

[Stefan Hermann] of [CNC Kitchen] created an excellent spreadsheet to calculate and itemize the costs of 3D printing, and it also provides a nice pie chart of where time and money are spent. It can easily be adapted to any kind of service that uses a machine to create a physical deliverable, like laser cutting, CNC work, or anything else.

People who aren’t sure what more there could be to it besides the cost of materials and maybe power might be surprised to discover that setup time, post-job finishing, and hardware depreciation all add up very quickly. (Depreciation is important to include. All machines cost money and no machine lasts forever, so there is an inherent cost to operating one.)

[Stefan] has a video overview explaining his spreadsheet in more detail. Remember that the goal is to understand your own time and costs. Also note that the spreadsheet doesn’t address shipping, so don’t forget to account for those costs if your product is shipped.

Do You Provide a Service With No Physical Deliverable?

If your work doesn’t involve physical objects, the principles are still the same. It just means that you will be focused mainly on one type of currency: time. [Gerrit Coetzee] explained how to properly estimate project time, which is full of useful insights into how time actually gets spent on a project and will help you break a task down.

Again, it’s not necessary to break things down to the last detail. If you know where your top three highest expenditures are, you have what you need to proceed.

What’s Actually Important to Your Client?

Understanding your customer’s needs and values is critical. It will also help in figuring out what their budget is. Most clients won’t have a firm budget, or they won’t want to tell you what it is out of fear of tipping their hand in some way.

Happily, getting answers can be as simple as meeting and doing more listening than talking. Don’t be afraid to ask questions or request clarification. You are done when you feel confident that you have an answer to these questions:

Happily, getting answers can be as simple as meeting and doing more listening than talking. Don’t be afraid to ask questions or request clarification. You are done when you feel confident that you have an answer to these questions:

- What is it that they are trying to accomplish?

- What exactly is it that they want you to do for them?

- How urgently do they need it done?

- Where will the difficulties be?

If you’ve had good communication, you should have a solid idea of what they value most, and why.

Putting it Together With Two Steps

Once you know your own costs and you understand what your client values most, you have what you need to find opportunities to reduce costs in a way that benefits everyone.

1. Always deliver on whatever the client considers most important.

No matter what, you have to give maximum delivery on whatever your client values most. Deliver the best results you can. No cutting corners here.

2. Save the cost-cutting for the things which are expensive for you, but less important to the client.

Out of the remaining elements of the job, the best targets are those that are all of the following:

- Expensive for you to perform in terms of time or money (relative to other tasks)

- Do not require your personal specialized skills or tools

- Considered of lesser importance by the client

Tasks that are expensive for you but do not need to be done by you personally are your starting points. Moving them off your plate and onto the client’s is how to reduce costs in a way that doesn’t amount to simply charging less for the same amount of work.

Examples

- Have the client provide data in a way that gives you a simplified toolchain or workflow. For example, if you accept .DXF files for laser cutting, have your client agree to send their designs pre-organized into sheet sizes that are convenient for you.

- If you apply specialized tools or skills, have the client do the other work. For example, on circuit boards you might install surface mount components and program the microcontrollers, but the client can perform uncomplicated (but time-consuming) tasks like soldering through-hole components and wires.

- Provide finished parts or modules, but let the client take care of the assembly or integration.

- The client does post-processing tasks like sanding, painting, or other finishing touches.

- The client agrees to provide raw materials in a format you can easily work with (in a way, have them do your purchasing, prep work, and delivery for you.)

It’s worth mentioning that the client should be able to actually perform whatever tasks are being negotiated. It’s no good having them agree to take on a task if you end up spending a week on the phone doing it for them anyway in the end.

If None of Those Applies

There are other, more creative ways to reduce costs without devaluing your own work:

- Be sure to communicate where the biggest costs are coming from on your end. Can any of them can be substituted for cost-saving alternatives that still deliver what the client needs? They may not be aware of the options, and they may not have considered doing things a different way.

- Share some of the client’s risk by making a portion of your fee dependent on project milestones or performance. Anything that can be measured can be the basis of a performance-based fee or bonus that can translate to a lower up-front cost, but balance out for you later.

- Non-monetary benefits such as use of equipment, services, or space can also be negotiated to reduce fees. Does your client have or produce anything that you would find useful?

Remember that your value will be measured by how well you deliver on whatever the client considers most important. Delivering on that is what will get you invited back; it’s an important way to avoid failing as a contractor. It’s also a good way to get included in conversations that begin “who do you know who can…” which is an important way to find work as an engineering contractor.

Remember that your value will be measured by how well you deliver on whatever the client considers most important. Delivering on that is what will get you invited back; it’s an important way to avoid failing as a contractor. It’s also a good way to get included in conversations that begin “who do you know who can…” which is an important way to find work as an engineering contractor.

For those of you looking to create and sell physical products, don’t forget the excellent tips we covered when we asked: Will It Sell?

Do you have your own experiences to share in finding ways to reduce costs without affecting delivery, or understanding your own costs better? Let us know in the comments.

thanks for this kind of information, especially because lot of engineer is not a business guru :) the basic idea is that the customer wants the product to be ready immediately and for zero price and the developer wants it to be ready in infinite time and for infinite money :) so if booth want to win, then they need to negotiate those extreem terms…

Except both want to meet those condition in 0 time. No one wants to spend an infinite time on anything.

I find a lot of customers are smart enough that they don’t want zero price other than for commodities; for professional services they’ll refuse to pay below some floor that they consider the minimum, anything below it they assume is a scam or substandard work.

Being an independent contractor in IT has one major advantage – you get to preserve your sanity by not having to cock about with SCRUM or other “new and more efficient management techniques” that only result in 75% less work done.

Spot on. Valuation is probably one of the hardest things to get right on offering any service. Always make sure there’s a clause for billable on post delivery services and clearly define what’s included.

Agree. I’ve have a hard time with it. I started with ‘what’s the lowest price I can afford to charge’ instead of market value, which was a mistake. Pricing is not really like engineering, it turns out.

I ended up with clients that were cost-focused to the point of being outright rude. People belligerently demanding months of work for free or close to it. Companies in a mess because they just take the proposal from the most expensive contractor and give it to the cheapest one. That sort of thing. Took a year to restructure and fix.

In hindsight, I consider my past-self as incapable of prioritizing and hilariously inept at business overall. I’m no genius now, but things are OK. I hope you all have an easier time adapting to it than I did!

I looked at the model. Quite a bit missing from the costs structure. There are costs for inventory, rework and quality that should also be comprehended. In addition the costs calculations should match the cashflow laid out by the agreement. For example, what are the milestones, Incoterms and Acceptance? Is there a requirement for warranty and indemnification? If so these are also costs. One last point-if you are not using accrual basis you should consider switching. The process for matching costs in period will help to clearly expose the difference between cashflow and profit. When you are on your own-it is easy and risky to confuse having good cashflow with having profit.

Below is a link to a cost model we used at a Contract Manf to cost services work. This may be helpful to better understand tje complications of costing. The model also has macros that perform monte-carlo simulation of how the work arrives. If the work is steady, the costs are lower. If the orders fluctuate-the costs will be higher.

https://drive.google.com/open?id=12Tn5IxU5EdGsRz18EdiF1EDqYvw_0pv3

i feel like i just violated an NDA

Anyone who asks me if I’ll work for “exposure” or “referrals” gets deleted form my contact list.

Yeah, while some people truly don’t realize where costs come from or why, some are simply aiming to take advantage of others.

The old cliché:

————————–

We offer:

1) Low Cost

2) On Time Completion

3) High Quality

—————————

As my customer, you get to pick any two of those requirements.

Kudos for what is probably the most important subject for people new to indy contractor work. Someone (other than myself, of course) needs to write a three or four part series on this subject, as it is overly complex and full of edge cases.

During past 30 years have gone from mostly service to project contracting, and am now just doing custom versions of hardware systems developed for previous contracts. This has reduced cost uncertainty and allows some amount of recurring customer work (aka, customer lock-in).

Then there was the group of enthusiastic young grad students that saw my box’s price and told one of my customers that they could do that for less than 30% of the base price. While their BoM was probably less than 50% of my cost, it took them over 400 hours of engineering time, and significant support time, so am guessing that they made under 5 USD/hour. But am certain that these kids’ experience was priceless….

For the Hackaday readership, this article is excellent. Covers a lot of topics that many failed Kickstarters don’t consider until it’s too late for recovery. The Sample Costs Calculator is a nice example of a simple overview for costing models.

From a professional perspective within the EMS industry, I can say that this is something I deal with daily. The labor quoting model we use currently consists of assembly data, setup/cycle time data, build sizes, labor rates, variables to support the hundreds of formulas, and summary cost data for pricing to the customer and setting the standard for production routings (a routing is the sequence of tasks to build a product).

In addition to the above great ideas, it can improve flexibility of the project when the client can’t afford the upfront costs entirely: equity. There’s always some agreement about the handling of those profits, so that balance point can be moved to accommodate this. I’ve worked with companies small enough they could only afford a small stipend per week, but instead cut me in on the overall later payment. Of course, all such things don’t work out, but if you have the flexibility and the client has the need and willingness, it’s something useful in negotiations and understanding of “valuation”. Why? Because there’s not a lot of things a business owner HATES more than the idea they’ll be skimming of some %age of their profit for long time in the future. It might not get you “more”, but it’s the kind of language they understand in thinking about the value of things, like their next vacation ;-).

Some thoughts or suggestions in the context of my small online custom jewellery design work…

With clients operating in different currencies to my own, I offered reduced prices if they paid in my currency, or if they paid in a way that reduced my banking costs.

For a client that sent multiple smaller jobs at once we negotiated to bundle up the billable hours rather than using a per-hour or-part-thereof method for each smaller job.

For a client that returned to me mutliple times we negotiated moving to billing on a per-minute basis, but at a slightly higher rate than per-hour-or-part-thereof.

For a client that expected to be requesting a large number of similar design variants over time I charged them extra to develop a completley parametric design, with a fixed fee for each iteration.

For a client that was worried about the costs of manufacturing prototypes and samples, I acted as a consultant on the most suitable lower cost materials and contract manufacturers that would still give a result that reflects the manufacturing and dimensional issues expected in the final version. I also developed various lower-cost versions (i.e. hollowed out, thinner, fewer of a repeating sections etc.) that would be good enough for a “look-and-feel” prototype.

For a client that provided undimensioned sketches I told them I could charge a lower price if they provided more detailed drawings and additional dimensions.

These are great, and inventive as well!

Really shows that you need to know your own end of things in order to craft these kinds of clever solutions. Thanks for sharing!

Great tips here! Subscribing to comments in case somebody else has to say something.