Old cars are great. For the nostalgia-obsessed like myself, getting into an old car is like sitting in a living, breathing representation of another time. They also happen to come with their fair share of problems. As the owner of two cars which are nearing their 30th birthdays, you start to face issues that you’d never encounter on a younger automobile. The worst offender of all is plastics. Whether in the interior or in the engine bay, after many years of exposure to the elements, parts become brittle and will crack, snap and shatter at the slightest provocation.

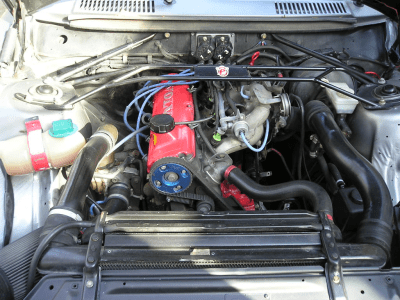

You also get stuck bolts. This was the initial cause of frustration with my Volvo 740 Turbo on a cold Sunday afternoon in May. As I tried in vain to free the fuel rail from its fittings, I tossed a spanner in frustration and I gave up any hope of completing, or indeed, starting the job that day. As I went to move the car back into the driveway, I quickly noticed a new problem. The accelerator was doing approximately nothing. Popping the hood, found the problem and shook my head in resignation. A Volvo 740 Turbo is fitted with a ball-jointed linkage which connects the accelerator cable to the throttle body itself. In my angst, the flying spanner had hit the throttle body and snapped the linkage’s plastic clips. It was at this point that I stormed off, cursing the car that has given me so much trouble over the past year.

Getting Back on the (Broken) Horse

Of course, I didn’t give up that easily. A few hours later, my enmity for the insolent Volvo had cooled down to a low simmer. I inspected the broken linkage and decided it would be an easy fix after all. I lathered the broken pieces in epoxy, wrapped them in paper to add strength and topped it all off with a small ziptie for good measure. I left it to set over night, and popped it on first thing in the morning.

Success! I started the car, and got a full 200 meters down the road before the accelerator once again became limp and useless. After pulling over, I found that the other half of the linkage had now broken off, and having fallen out on the road somewhere, I wasn’t going to find the pieces anytime soon. I left the car at the side of the road, got myself off to work, and began the search for replacement parts.

Alas, owning a European classic in Australia was hurting me. I could source the plastic ball-joint clips I had broken, sure – but for the princely sum of $50 by the time shipping was over with. This wouldn’t do. Instead, I decided to head to the wrecking yard, which appeared to have a car matching mine.

Upon arriving, I was dismayed to find that there was no car akin to mine at all! A day driving my race car to work had been irritating enough, so I wasn’t ready to give up yet. I scoured the yard for similar cars, and found a couple with similar linkages, and in the end, a Volvo 850 bore fruit. Pleased with what I’d found, I headed home, with the wrecking yard giving me the part for free. Kind chaps!

Getting home, I found that while the ball joint clips were the same size, the new linkage was far too long. The linkage uses an interesting method of adjustment. One plastic clip is permanently attached to the shaft, and doesn’t move. The other clip has a screw-on cap, underneath which there are several washers. When the cap is tightened onto the clip, a special washer inside is deformed and expands outward, gripping the shaft tightly and stopping the linkage from changing length.

Customizing Salvaged Parts

At the maximum extent of adjustment, it still wouldn’t fit, so I got creative. Undoing the adjustable clip, I found a circlip fitted to the shaft which acted as a stop for an internal spring. However, this only seemed to serve the purpose of stopping the washers from falling off the shaft. I removed this with pliers, and then all the internal washers. I then simply took out the angle grinder and cut the shaft down to the necessary size.

After some fiddling, I determined that the washers had to be assembled in a particular order to make them work properly. I then laid the new linkage next to the old one to set the length the same as the original part. This was important, as I had no interest in spending hours tinkering with the full adjustment process for the throttle body. I gingerly approached the car, and to my great relief, the new linkage clicked into place without a problem. Happily, the car has since completed many miles and has been free of further breakdowns.

There is Power in Greasy Hands

In this day and age, it can be very tempting to just throw one’s hands up and replace something broken, or in the case of cars, just give up and trust the dealership to fix it. Granted, when the chips are down and your only ride is out of commission, sometimes the choice is out of our hands. But something to remember in this replacement culture is that repair can be possible, and can even be remarkably easy.

The real bonus is that you can learn something along the way, and if you’ve got the love for the project, putting your own labour in doesn’t sting so bad. The lesson I learned was that while you can’t always source the correct parts, that doesn’t mean it’s over. With a little ingenuity and a willingness to do the work to make things fit, it’s often possible to get yourself out of a bind, and usually pretty cheaply, too.

Now, there’s every chance that my “new” part will only last a few years, given that it came from a car that itself was only a handful of years younger. But for now, I am once again enjoying my classic vehicle on a daily basis, and it cost me practically nothing! I’m calling that a win.

How did you manage to take a picture of the linkage that went missing?

He traveled back in time. He has an old Volvo, after all.

Nice one. So few would get this reference.

Who you are referring.

It was the piece that broke off that went missing, which you can see in the picture – there’s only half a ball joint left on one side :P

All plastics in a high heat, oily, and volatile exposed environment have a limited life which begs the question-why are they used so frequently in those environments?

It’s almost as if the manufacturers want them to fail!

totally agree, it only lasted >26 years

^ this. FFS it’s not like Volvo are known for under-engineering things.

There have been a few notable exceptions over the years.

We don’t speak of the Peugeot-Renault-Volvo V6…

@carpart122, that’s the significance of 88mph…the PRV-powered DeLorean can’t go any faster!

And we all know plastic compounds haven’t been improved at all since then.

Lowers the initial cost, warranty only lasts so long anyway. Have to compete with others who do similar things. OEM doesn’t have to do the repairs. They would prefer customers buy a new car anyway than repair things.

Doesn’t make it right but that’s a big part of why things in vehicles are commonly engineered the way they are.

*slowly reaches for the tinfoil roll*

Because it’s cheap. You could build the perfect car with every component engineered to last >30 years without much maintenance, but it would be incredibly simple, heavy, low tech, cost hundreds of thousands and no one would buy it. People would say “wow, for that price it doesn’t even have a 9 speed gearbox? No parking sensors? And it costs that much!?”

Volvo did pretty well with the 740, really.

See: USPS mail trucks https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grumman_LLV

Especially 80’s early 90′ cars have brittle plastic. Took the airfilter box off my then Renault Kangoo in freezing temperatures and handling it slightly rough broke it in 3 pieces. Working it over with a soldering iron fixed that. Don’t handle plastics when it is cold!

French cars in general should not be handled when it is cold

Or handled at all? Jk, but I certainly do prefer German cars…

Because it’s “good enough” to outlast the warranty period and way cheaper in manufacturing.

You realise they stopped making this car in 1992 right? That’s one hell of a long warranty or one hell of a defective tinfoil hat.

Because a car that old probably won’t / shouldn’t pass modern emissions or safety tests.

Cost.

Yup; as an owner of two 1985 german cars (merc w123, and vw Fox) I can say that anything plastic from that era is dead. It’s OK as long as you don’t try to touch it; but once you do the spirits holding the plastic together leave; and it instantly crumbles or shatters.

Thankfully the w123 seems to have avoided using plastic for anything mission critical. It has a similar throttle linkage; but it all metal and just needs some new grease every couple of seasons.

That being said; I have had to do some hacky fixes myself to drive with a dead glow plug relay; dry-rotted muffler rings; and a stuck trunk lock.

Image of throttle linkage:

http://www.benzworld.org/forums/attachments/w123-e-ce-d-cd-td/242081d1243975534-throttle-linkage-diagram-img_1821.jpg

Can confirm that ’80s Volvo didn’t test longevity of their plastics in hot climates. Door panels and dash inserts inevitable turn into peanut brittle after just a few years. Most annoying are the tail light lenses that fracture at the edges, letting water in to corrode away the “clever” flex PCB they used for the bulb connections.

Oh those plastic door pockets Volvo used in the 80’s were absolute trash in every environment. They’re perfectly placed to have your shoe smack them every time you get in and out of the car.

The W123 has more to worry about than the plastics. The way the boot (trunk) separates from the rest of the car due to cracking of the metalwork over the back axle is enough to worry about. Thankfully you can’t really see it because the fuel tank is on top so sleep easy.

I had older VWs that were plagued with similar plastic snap ball joint shift linkages. There are kits available to replace them with threaded rod and sealed metal ball joints, though the shifting was never great due to the design.

If this were my car I’d probably build something similar to replace the plastic joints. I don’t know what the ball ends look like but it’s probably not too hard to grind/drill the ends and replace them with real ball joints. Hope you at least got a new OEM link on the way otherwise your junkyard one probably doesnt have much life left in it either :)

Got a old Passat with that, ended up jury rigging shifter mechanism from a newer VW with similar linkage except better designed.

Required some mild adapting.

A couple of automotive hacks I’ve heard over the years.

When the fuel/air mixture was too rich at high altitude.

a. one owner removed the air filter to allow more air in.

b. another super glued the carb jet closed and re-opened it with a stick pin (smaller hole, less gas).

My dad, on cold winter drives, would partially block the radiator on our old family car with a piece of cardboard, because the cooling system wouldn’t get hot enough for the thermostat to open.

I once drove a Datsun pickup 100 miles with its thermostat stuck closed. The engine was not damaged, perhaps it was because it was -20 F when I did it.

B^)

most every taxi driver in the UK does this in the winter, or certainly, did this lol times are-a-changeing.

Details stated awkwardly. I reality on many vehicles the thermostat would open it has to for radiator shuttering to have an effect. The reason for shuttering the radiator is that with the thermostat open the coolant would never stay warm enough for the defroster and heater to work well unless the radiator was shuttered. Trucks powered by Detroit 6-71 engines had iceboxes for caba no amount of radiator shuttering get the coolant warm enough.

I used to do that – I’m sure I’m not your Dad :-)

I still do. My 800cc diesel Smart doesn’t make enough heat to dry hair.

Radiator is completely blocked all year round and it still doesn’t stay at normal temperature if I have a long downhill without throttle.

Is that why taxi drivers round here all drive with cardboard stuck to their radiators? Or is it because it’d just be freezing in the taxi? — UK, this happens when we have lots of snow (which isn’t often tbh). I’ve never though to ask one why.

Many large trucks in the colder parts of the US have a radiator cover with a zipper to adjust the amount of blockage. It’s sure they’re sold at most truck stops.

I had to fix a shifter linkage in my Fiat X1/9 by drilling 2 holes and adding bolts, after using a generous amount of RTV on the inner surface (it was two metal disks with a rubber between them, apparently to dampen vibration between the transmission & stick). It worked for years after that.

Hey @Lewin Day, did you ever find the cause of your 740’s high fuel consumption?

https://hackaday.com/2018/04/05/lazy-hacker-checks-fuel-system-for-leaks-the-easy-way/

Still workin’ on it!

Should have went to your local RC hobby shop for some Helicopter / Airplane Ball links. Dubro probably make on that would have worked.

Also available at any decent auto parts store.

At least suitable repair components should be at the auto parts store. Many makes use similar linkage

Didn’t even think of that, though now you mention it, I remember seeing some adjustable carby linkages that may have been good…

The throttle linkage on an old Ford winch truck I was driving fell off went going up a hill. I found the problem after coast back down the hill. Finding nothing in the truck to fix it I notice the barb wire fence, the wire tails used to wrap around the wire where way longer than usual. I used the fence strechers in the tool box get get control, then I undone the wrap cut off the length of wire I needed, put the fence back to to right. I then wrapped the wire around the balls that the OEM linkage used. Hack worked because the linkage operated under tension. Decades later the fence is working as constructed

Back in the 1960’s, my brother had the timing chain on his Honda Trail 90 break 100 miles from the Honda dealer.

4 hours later in near freezing weather and some barbed wire from a nearby fence got him back home.

How can you replace a timing chain in the field and with only some barbed wire? Especially when normally a broken timing belt or chain makes the pistons hit the valves -> R.I.P. engine.

He used pieces of the barbed wire to _repair_ the timing chain. Being that it was a 1960’s era engine, it may have not been interference. He arrived home to tell us he was okay and immediately left for the dealership without shutting off the engine.

I think a better “hack” is when my cousin used the elastic band from his undershorts to replace a broken fan belt on his 1970’s era Ford LTD.

a couple pair of nylon panty hose was a not-uncommon recommendation to have in the toolbox for a car with a bunch of different V-belts. If one failed, you didn’t have to remove all the other ones to get the replacement in, and you could tighten the nylon hose to meet your diameter requirement.

Now of course there are the link belts (very handy for dampening vibration in belt-driven shop tools), which you can make to size by removing/inserting link sections – but of course, modern cars now use serpentine belts.

When you replace a worn serpentine belt, it’s not a bad idea to put the old one in the boot in case you run into trouble on the road.

When my brother worked on performance rotary engines they often had to rework the throttle linkages around some of the aftermarket things they’d done to the air/fuel side of things. He used RC car servo linkage pieces to build replacements and never had any of them fail.

Throwing things has rarely worked out well for me. It may work out well for golfers, but I think even for them it tends to work out poorly. In general nobody is impressed.

Absolutely true.

Spanners also turn out to be startlingly bouncy when you throw them at a solid wall.

And they bear a grudge…

I had a vacuum leak once that I just could not find. The engine would run fine if you stepped on the gas, but would not idle. There was a tube going up into the air filter…I found if I plugged it, it would idle fine, but had no power and would stall on take off. I took the rubber end off of a fishing pole, plugged the end of the tube in the air filter, and cut a small hole in the center of it. It still idled, but not quite enough power, so I kept enlarging the hole until it both idled and ran well. Lasted 3 years before I finally junked the car…..

I had a mitsubishi montero with the 2.6 and its famously bad carburetor. It stumbled badly and ran just bad altogether. The carb’s vent bowl valve was broken, no longer closing. A drill bit inserted into the line that goes to the charcoal filter plugged it up and it ran beautifully after that. The idle circuit dumped fuel still, but as soon as it went to its main circuit it was fine. Even got 19mpg with it on a trip :)

The best side of the road hack I’ve ever done was when a heater hose on my then 15 year old rustbox 1978 Chevy Van blew in the middle of a 2 hour drive. I ended up wrapping the blown hose with a cut up Mountain Dew bottle and several zip-ties, and I refilled the radiator from a muddy stream that happened to be fairly close to where the van broke down (the old 305 engine was practically junk, so I didn’t care about using dirty coolant). This repair lasted for the rest of the drive home, at which point I stopped into a local auto parts store for some generic replacement heater hose. Total cost of repair: $3.

You could have also found an 1992 BMW with the M50 motor in it as it has the almost exactly same throttle body setup on it. It’s like Bosch desgined the whole fuel injection & intake system on most of the European cars built between 1978 – 1996. You can use parts from Porsche, BMW, Mercedes, Audi, VW, Saab, Volvo (not sure about the italians or the french). Or 5min on google found the manufacturer of the offending ball joints. Found the part numbers and googled them and found them on ebay. Trouble in if you dont live in the USA postage is always astronomical.

Yeah, that’s the exact problem I had. Wanted the car back on the road ASAP and for cheap. Found the right parts quickly enough but they wanted $40+ for them after shipping!

Think my 5.9 Cummins runs the same injector pump as a VW Rabbit-just 2 more cylinders and more volume.

Bosch VE. The major difference is the cam plate and pump head.

Ball joint linkage…? Can think of MANY parts sources. McMaster carries them. CB performance, heck even gopowersports. Not rocket science.

Definitely not rocket science, it’s a throttle body on a 1980s Volvo. Internal combustion is quite different. Rocket science is cool too though.

One of my mates arrived at work with another mate under the bonnet operating the throttle by hand while he drove with his head out the window ace-ventura style, shouting commands.

Happily they hadn’t come far.

“hood” in Australia? Seriously mate?

I had a 1970 VW bus with an aftermarket carb that had an extra air intake port not needed on the bus. Previous owner has sealed it off with some sort of RTV or something. Driving one day and it starts sucking air like crazy – the sealant was gone. Turns out that a dime (US ten cent piece) fit over the hole perfectly. Held it in place with a rubber band and drove home!

I heard few stories of temporary V-belt replacements with pantyhose … Urban myth or … ?

Alright, Hackaday. Looking at the great stories about car kludges here in the comments, and wondering if you’re getting the same article idea that I am. Very entertaining.

Reminds me of this.

https://farm8.staticflickr.com/7474/15616785717_6a9897137f.jpg

The ends of the plastic ball clips tend to snap with time and road dirt.

Part not sold seperately.

I ended up replacing my shifter bushings for my vintage Audi Quattro with 3D printed PLA. Still going a year later.

https://www.thingiverse.com/thing:2558263

Better yet – my 740 turbo wagon died on the road one day because: (wait for it)…a small, straight piece of metal (looked like a piece of capacitor lead) that for some reason was mounted on the gauge cluster’s PCB (backside) fell off hitting a bump and shorted out the tach – immediately killing the electrical to the engine. Very experience Volvo mech almost lost his mind trying to fix this crank-no-start. Found that – removed it – car started right up. All this @ 28 years old. But at least the sunroof seal is still supple and no leaks!

I made it home from quite a ways back on a public access road in a National (US) Forest by using my bootlaces to replace the broken throttle cable. Removed tc assembly and routed the laces through the hole in the firewall. Neat part was that on those 80s Ford trucks the cruise control used a separate cable. All I had to do was use my new hand throttle to get back to pavement and then I could use cruise to give my hand a rest. I did have to buy a new tc the next day, but at least I didn’t have to walk out 12+ miles to pavement.

Reminds me of a problem I had with a gear shifter cable snapping on my bike… this got me out of low range:

http://virtatomos.longlandclan.id.au/~stuartl/bikeforums/2015/04/22-cable-splice/cable-splice.jpg

Wait…you’ve got a near-30 year old TURBO, and you’ve never had an engine/ turbo problem? I know you didn’t say anything about this aspect, but I’m giving you the benefit of the doubt.

Care to respond?

I’ve only had this car for like… 9 months or so.

It’s had:

Auto Transmission issues, jamming in gear (fixed by replacing filter)

Fuel economy issues (suspect leaking injector, fix to come)

Brake issues (dud booster, at mechanic to get replaced this week)

And has had an engine replacement in its past.

…sounds like you’re on your way to having a car that’s just getting ‘broken in good’.

Just remember to change the transmission filter and fluid once a year–religiously. And don’t abuse the turbo; treat the engine (drive the car) as if it didn’t have one.

Nice car.

My best/worst hack was on a 1993 BMW, the radiator fill tank cracked and leaked all the fluid out. Roll of duct tape, a bit of super glue and tap water got me going for a year until I junked the car. From there on, duct tape and super glue is part of my tool bag.

I bought a 1985 Fiero about a decade ago. After 8 hours of driving, and still 4 hours away from home, I started losing speed and had to pull over. The previous owner failed to replace the heat shield that was supposed to be over the exhaust manifold, and it melted the throttle cable. When the throttle cable went limp, the retaining clip holding it to the throttle body came loose and was forever lost to the highway. In a short time, a cop pulled over and asked if I needed a tow…

I asked if he had a clicky pen.

I had a plier, a roll of duct tape, two zip ties (found in the trunk), and a paperclip. Pulling the EGR tube off (to use as a makeshift heat shield), a cable guide tube (pulled off a wire harness), and the spring from the pen, I was able to rebuild the throttle cable, shield it from the manifold heat, and reattach the end to the throttle body, using the pen spring and the paperclip.

I drove the car like that for a full month before getting a replacement throttle cable.

Coming from Sweden I found it amusing to see a 740 being called a classic.

They used to be one of the most common cars around here and I don’t think a day goes by without seeing at least one 740/760.

741 is a classic. One was knocked-off in an accident, and it became the 740.

If you tune in a “classic rock station” you will find that the word “classic” does not mean what you think it means.

Fuel economy–

“…Fuel economy issues (suspect leaking injector, fix to come)…”

“…Upon letting the car down, there was a resounding crunch and the car’s full weight was now on the ramp I’d left sitting directly under the fuel tank… in the following weeks, my fuel economy had become terrible…

“…Dropping the tank for inspection promised to be a big job, and ideally would be done when the tank was empty to avoid being crushed under the weight of 50 liters of fuel. There had to be a better solution…”.

My assessment from 12 000 miles away? I’d like to have back all the time I’ve wasted because I just knew there had to be a better solution.

The fact that gas mileage immediately went into the tank–pun intended–as soon as you seriously compressed the tank by letting it down on the support is extremely suspicious. Seems to me as if you might have damaged the fuel-return line/mechanism from the injector system to the tank which, of course, would live out of sight, unable to be inspected except by dropping the tank. The simple system which returns unused fuel from the injectors to the tank is an extremely important factor in the good-gas-mileage equation.

As long as you’ve dropped the tank, inspect everything INSIDE the tank for damage also (and replacement, while you’re there); my 2000 Dodge ,for example, makes me drop the tank just to change the fuel filter. But I do get a new fuel-gauge sender for my trouble–and you just know how those pesky little devils need to be replaced as often as the fuel filter…

Nice car; best of luck…