It was darkest hour for the video game industry following the holiday shopping season of 1982. The torrent of third party developed titles had flooded the home video game console market to the point of saturation. It incited a price war amongst retailers where new releases were dropped to 85% off MSRP after less than a month on the shelves. Mountains of warehouse inventory went unsold leaving a company like Atari choosing to dump the merchandise into the Chihuahuan desert rather than face the looming tax bill. As a result, the whole home video game industry receded seemingly overnight.

One company single-handedly revived video games to mainstream prominence. That company was Nintendo. They’re ostensibly seen as the “savior” of the video games industry, despite the fact that microcomputer games were still thriving (history tends to be written by the victors). Nevertheless their Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was an innovative console featuring games with scrolling screens, arcade-like sprites. But the tactic they used to avoid repeating the 1983 collapse was to tightly control their market using the Nintendo Seal of Quality.

From the third party developer perspective, Nintendo’s Seal of Quality represented more than just another logo to throw on the box art. It represented what you could and couldn’t do with your business. Those third party licensing agreements dictated the types of games that could be made, the way the games were manufactured, the schedule on which the games shipped to retail, and even the number of games your company could make. From the customer side of things that seal stood for confidence in the product, and Nintendo would go to great lengths to ensure it did just that.

This is the story of how an Atari subsidiary company cracked the hardware security of the original Nintendo and started putting it into their unofficial cartridges.

“There were some urban legends in the very early days of the Famicom. Nintendo allegedly used some strong arm tactics at the retail level and they forcibly discouraged reverse engineering of the platform.”

– Mark Morris, Former Tengen Programmer

Here Comes The Rabbit Chip

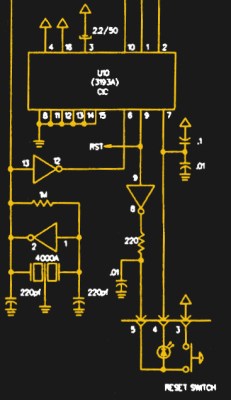

The other half of the seal was Nintendo’s security lockout system known as the 10NES program. Essentially the program consisted of a “master” IC inside every NES control deck and the identical “slave” IC inside every game cartridge. Upon inserting an official game cartridge and powering on the console, the LOCK on the master IC sends a reset and initialization signal to the KEY on the slave IC. If the correct response is returned the game cartridge boots the game, but if not the CPU/PPU RESET lines are pulled low with a 1Hz square wave accompanied with a solid color blinking screen on the display. Due to Nintendo’s stringent licensing terms if a company wanted to publish on the NES the 10NES program was the only way in… until Tengen came along.

Tengen, a subsidiary of Atari Games, was initially created to port coin-op arcade games onto home platforms like the NES. Tengen hardware engineers sought to reverse engineer the NES CIC through a chemical peel, but when those efforts failed to generate a complete bypass solution the company decided to become a Nintendo licensee. Upon becoming official, Atari Games lawyers sought out a loophole in order to obtain the code for the 10NES program via the US Copyright Office. By stating that Atari was a defendant in a 10NES program infringement case and therefore was privy to that information, however, no such lawsuit existed at the time of the request.

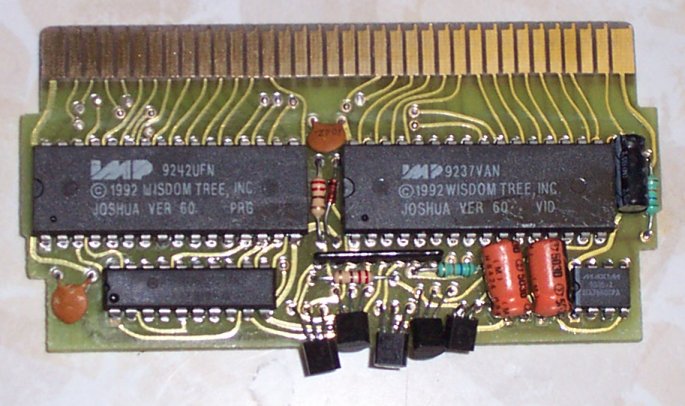

A shady move to be sure, but combining elements of the newly acquired code with the Tengen engineers’ silicon design the NES’ lockout chip was cracked. They called it the Rabbit chip. This chip meant Tengen were the masters of their own destiny, and allow them to release games like RBI Baseball that featured actual MLB players. However, the people creating the games were not aware the Rabbit chip existed.

“I was completely naive to what was going on…I had no idea, I thought we were going through standard Nintendo.”

– Steve Woita, Tengen Programmer

One Small Step For Tengen, One Giant Leap For 3rd Partys

Unsurprisingly Nintendo would retaliate against Tengen releasing unofficial cartridges. In 1990, Nintendo of America sued Tengen for copyright infringement of the 10NES program. Tengen’s defense hinged on the idea that the Rabbit chip needed to function indistinguishably from the 10NES chip in order to prevent Nintendo from barring Tengen from releasing games on any future revision of the NES hardware. Tengen even called into question the validity of the lockout system patent for its obviousness, but it was all to no avail.

No doubt emboldened by Tengen standing up to Nintendo, other third party developers like Camerica, Active Enterprises, and Color Dreams created their own 10NES bypass circuits. These methods typically involved creating a charge pump in an attempt to “stun” the CIC lockout chip. Users of those game cartridges were unknowingly causing damage to their consoles’ less voltage tolerant parts, but the allure of having dozens of games packed into one cartridge like Action 52 would be a novelty too sweet to pass up.

At the time, the Nintendo Entertainment System was in 33% of all American households. With that kind of market penetration, other game systems hardly mattered. So a couple of years after the copyright infringement case, Atari Games would challenge Nintendo’s virtual monopoly on the videogame industry in court. The antitrust case brought against Nintendo would not reach a decision as both parties agreed to an undisclosed settlement, however, it stands to reason that if the case had gone in favor of Atari Games the video game world would look very different than it does today.

Tengen challenging Nintendo at the height of their influence ultimately changed the way third party developers coexist with platform holders. Each side would treat each other more like partners, because the success of a video game platform is forever entwined with the software written for it. The introduction of the Rabbit chip set a precedent that no game console security was beyond scrutiny. Who knows if history had gone a little differently we might have received a few more ports like the unreleased Tengen version of Marble Madness in the video below:

I had marble madness on the NES in a Tengen cartridge so I think there was a limited release. We got our copy as a sample that was sent to the video rental store where my stepfather worked…

At least I’m fairly sure that one was on the NES, I remember we had two games in the Tengen cartridge (the black ones with the curved top) and I think marble madness was one of them. The other was the Tetris where you could launch missiles when you got high scores (rather than the dance number on the Nintendo release of Tetris, and the music was better on the Tengen version).

Marble Madness was certainly released for the NES in the PAL region. This usually means there also was a Japanese release on Famicom.

I don’t mean to interrupt but Marble Madness was very addicting. For me, it was one of the best arcade-to-NES translations ever made. I just wish it was like like Excite Bike that had a map editor for more fun and rage. I also had some problems with its controls. Nonetheless, it’s a hell of a game.

I remember playing Marble Madness on the NES, although I can’t recall if it was a Tengen cartridge. This one was a rental as well. The version in the Youtube video has a conspicuous difference: The black marbles aren’t moving like they moved in the version I played. Other than that, the video looks the same as what made it to stores.

Once Atari Games/Tengen settled out of court with Nintendo – per the dictates of their parent company Namco who hated the litigation costs more than they hated Nintendo – the company began licensing the titles to official third-party companies who were still marketing NES titles. Tengen then officially moved on to becoming one of the first official licensees for the Sega Genesis.

Nope, it was a legit release on the NES, published by Milton Bradley. Tengen games were all Namco, Sega, and Atari arcade ports, except RBI baseball series. Although, Marble Madness was an Atari arcade machine, Rare did the port for Nintendo.

We definitely rented Marble madness from the video game store for the NES. Not sure about the “unreleased” bit. It didn’t say it was a demo or anything like that on it. Had several levels, etc. We played the crap out of it.

“These methods typically involved creating a charge pump in an attempt to “stun” the CIC lockout chip. Users of those game cartridges were unknowingly causing damage to their consoles’ less voltage tolerant parts, but the allure of having dozens of games packed into one cartridge like Action 52 would be a novelty too sweet to pass up.”

Apparently “too good to be true” and “buyer beware” advice didn’t exist back then.

Same reason we started cracking c64 software, not to pirate but to prevent the drive heads from being knocked out of alignment.

*riiiiiight* :P

It is such a recent problem that the Romans didn’t even have a term for “caveat emptor”.

Wisdom Tree also used another way to bypass the lockout for both NES and SNES: one just plugged a genuine game into the connector on top of their crappy game, and this unlocked the console…

Seal of Quality was Nintendo way to force every developer to pay for the right to publish on their console. As [Angry Video Game Nerd] can confirm, plenty of NES games were shitty. Just check out all the games by Laughin’ Jokin’ Numbnuts…

AVGN’s great. The brutal honestly and over-the-top reviews he does are coming from the heart of a true retro game fan.

Of all the ways to get around the lockout chip, that seems to be the best from an electrical and legal standpoint. You aren’t stunning anything with a charge pump and aren’t possibly running afoul of copyright laws and patents.

LJN’s horrible quality and incomplete games should be taken as a total disrespect for children. LJN handed broken garbage over to children, at great expense to parents, and expected us to buy more. Once in a while they’d come out with a pretty OK game, it gave children everywhere the experience of having an abusive boyfriend that sometimes brings us flowers.

“They’re ostensibly seen as the “savior” of the video games industry, despite the fact that microcomputer games were still thriving (history tends to be written by the victors). ”

THANK YOU! The “Nintendo saved the videogame industry” gets on my nerves every time I hear it.

Agreed. I can’t speak for everyone, but as for me and the friends I had back then, we never really noticed the “video game crash” because our Atari 2600’s still worked just fine (we all favored the Activision games over the genuine Atari ones) and our Commodore, TI, and various other microcomputers continued to play games, often ones that we programmed ourselves.

Crash? What crash?

Of course, I was only about 10 years old at the time…

Its still entirely possible they saved the video game industry as we currently know it. Unless micro computers had the same penetration as game consoles and the audience for such computers were into playing games, it is safe to say that developers would have really been struggling to stay afloat. I don’t think anyone truely thinks video games would have died altogether, but the face of the industry I think would have been completely different (maybe better but potentially a lot worse) had Nintendo not of succeeded in keeping consoles alive. The arcade scene would have remained pretty big for a while I imagine.

Do people really say ridiculous things about Nintendo like that?

Drew, you *are* aware that the PC-Engine was not, in fact, the NES, right? The title of the video is “PCE Marble Madness Gameplay”, The description on YouTube includes the sentence “As you may know, this video is from PC-Engine version of Marble Madness which was never released.”

It appears you don’t know what a “port” is in this context. A port is when you take a game for one system, such as the unreleased PC Engine game shown, and modify the code so it runs on a completely different system, such as the NES being discussed.

Oh, I see. As opposed to the PORT of the original arcade game, which Marble Madness was, to either the NES *or* the PCE. Take your attitude and shove it, twat.

No, no it isn’t. Did you take a wrong turning to end up here?

Wow. Has the PC Engine/TurboGrafx-16 version of “Marble Madness” been released to the community since then? There’s also 2 versions of it for the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive. One created by EA which was based upon their their Commodore Amiga version and then the superior Tengen Japan version which used some of the arcade source code just as “Gauntlet”/”Gauntlet IV” later did.

That time Atari “lied to the Copyright Office in order to get a copy of 10NES…infringed by reproducing a copy of 10NES that it was not authorized to possess… [writing a] program [that] was substantially similar to 10NES in ways not required to replicate the function of unlocking the NES console.”

https://www.eff.org/issues/coders/reverse-engineering-faq#faq6

What Nintendo never actually established was that the information was used. This was a smear, not an established fact, and the case transcript is way more complex than the public perception of it. As someone who knows some of the folks involved, I’ve heard from several people now that their implementation was running well before the data was accessed. But Nintendo needs you to think that (1) they saved the industry single handedly, and (2) Tengen couldn’t have produced Rabbit without that data’s help.

BTW, I’m not anti-Nintendo. But they are absolutely an enemy of reverse engineering, which I see as essential to legitimate historical preservation of video game history, and their PR always needs to be viewed with a jaundiced and cynical eye.

Its not a smear. Its a fact. If you take a look at the court records as well as that patent for the 10NES chip and Rabbit schematics, you will find that Atari lied about reverse engineering the chip. The problem is that the Rabbit Chip contains the same dummy code thats found in the 10NES schematics thats in the patent office filing. This was coding that was removed from commercial distribution versions of the 10NES. This is something that Ed Logg, the lead engineer at Atari Games, was never ever truly able to explain away despite claiming that Atari had sucessfully clean roomed the 10NES chip.

The source of the claim the “170mA trick” (aka. charge pump) caused damage came from Nintendo. Not exactly an unbiased org, and I never saw confirmation of that claim. Let’s add it to the list of claims which includes “Nintendo saved the industry”.

Nintendo also modified their console with – going from memory here – a zener diode on the line which blocked this trick from working. I can’t remember the year they did this, but that’s what led to the “pass thru” cartridges, which were far more expensive to manufacture, but the vendors had no choice after the Nintendo mod, as Nintendo had very cleverly made sure you couldn’t tell a mod’d device from an older model where the trick would work. So their backs were to the wall.

At the time I was working in a University and had access to a VLSI lab, and I was approached by one of these companies who was willing to pay us a few tens of thousands of dollars to reverse engineer the CIC. We politely declined.

Thanks for sharing ianfarquhar550343836.

> Those third party licensing agreements dictated the types of games that could be made, the way the games were manufactured, the schedule on which the games shipped to retail, and even the number of games your company could make.

…and most importantly, “What OTHER systems the developer may release the games for” (read: “generally none”)

It’s a great thing that some developers didn’t want to have such unfair restrictions put on themselves, and created a viable workaround.

The Famicom was introduced in Japan in 1983. When Nintendo introduced the NES to North America and Europe in 1985, along with the 10NES DRM, they were fobbing off two year old technology on the rest of the world. Nintendo was getting ready to introduce the Super Famicom exclusively in Japan in 1990. But North America had to wait a year. The rest of the world wouldn’t get Super Nintendo until 1992 or even 1993.

The delay was due to the fact that they weren’t at all convinced the rest of the world would be interested in a Famicom so didn’t set out to make one. Once near launch of the Famicom, a certain Swede was in the Nintendo offices and got to play on one and had an uphill struggle to convince them to release it outside Japan.

Dumping “ET” into a desert landfill was an insult to landfills. That was the worst video game… ever.

I don’t know, have you been on Steam lately?

Those on Steam are so bad I use them instead of bleach to scrub out the toxicity of CS:GO.

Superman 64 says otherwise. Funny, I beat E.T. back when I was 8 when it was originally released. However, I did RTFM which most people didn’t back then.

It was undeniably a bad game.

The controls were horrible too. When you fell into a well from the bottom side, you would have to fly out by pressing up, and then if you didn’t release it at exactly the right time, you would fall right back in.

Worst game of all time, I don’t know. There were a lot of other terrible games back then.

There was an article on HAD, I’m fairly sure, a few years ago. Somebody finally fixed ET! And, with the fixes, it becomes a mediocre game. Which is high praise considering.

Fixing the collision detection with the pits was a big thing, so now ET only falls in if his FEET touch the pit, rather than any part of his body. Since it uses a sort-of false perspective view, this is important. And yes reading the manual is essential otherwise it’s just an annoying little twat who keeps falling down hills for some reason that becomes a time challenge: can you refrain from throwing the fucking thing at a wall before the game timer counts down?

Anyway, worth playing the fixed version, just to see what it’s like in a parallel universe where it’s playable. Because in this one it’s an utter waste of space. You know they eventually found that pit and dug up some carts to sell as souvenirs? I wouldn’t be surprised if every one of them still worked, Ataris were tough!

https://hackaday.com/2013/04/06/fixing-the-worst-video-game-ever-e-t-for-atari-2600/

There’s the article I mention ^^ , I think.

Tengen’s release of Tetris is still my favorite. And another title they published that I rather liked was R.B.I. Baseball, it was a solid early baseball game for NES. What’s weird is for most of Tengen’s releases, I can’t imagine them having all that much trouble with Nintendo’s aggressive censorship. Hindsight being 20/20 and all.

Atari Games/Tengen went rogue because they hated Nintendo. They also felt Nintendo played favorites and shorted their orders for cartridges. Back then, if you were a Nintendo licensee, Nintendo manufactured all of the cartridges and limited the numbers produced, including cancelling orders. Each third party developer was further restricted to 4 titles released per year. Yet Nintendo allowed Konami to game the rules by creating the “Ultra” subsidiary. Tengen protested against this but Nintendo still allowed it so Konami got to release 8 titles instead.

Some things to point out.

The Atari Games Corporation [aka “Atari Games”] was the former coin-op division of Atari Inc, previously referred to as “Atari Coin”. And depending upon who you ask for their opinion, many consider it to be the “Real Atari”.

Atari Games came into being in July 1984 after Warner’s Atari Inc was broken up. The AtariTel division was sold to Mitsubishi, the assets of the Consumer Division [which handled consoles and computers] was sold to Jack Tramiel’s Trammel Technology Ltd. [TTL] company and became “Atari Corporation”, and the rest of Atari Inc’s assets were combined into Atari Coin and became “Atari Games”. Shortly thereafter, Warner sold a 90% stake in the company to Namco.

Atari Games had to use the “Atari Games” name on their arcade games. They couldn’t use “Atari” for branding any future consumer products – since Atari Corp had those rights – so they chose the “Tengen” name for their consumer brand since it was another term from the game of Go just like “Atari” and “Sente” were. The Atari Games/Tengen staff hated Nintendo because they felt the industry was their’s since they felt they created it in the first place and they – as well as Namco – hated the arrogance of Nintendo. Tengen’s unofficial cartridges were later painted black as a reference to the color of Atari 2600 cartridges.

Had Atari Inc stayed together, the 7800 would’ve been released in Christmas 1984 and would’ve revived the North American consumer video game industry. It was what the retailers – and consumers – wanted at the time: an advanced new console that was also backwards-compatible with the 2600 so the retailers hoped they could still get rid of their excess amount of 2600 cartridges they were stuck with. Retailers were openly hostile to any potential new console that wasn’t compatible with the 2600 which is why Nintendo of America had so many of their efforts rebuffed from 1984 to 1986 in getting what became the NES launched here. But Atari Inc was broken up and many disagreements happened between Warner, Atari Corp, and GCC [the designers of the 7800] so it wasn’t ultimately launched until early 1986.

Going back to Atari Games/Tengen, they were reverse-engineering the 10NES lockout chip which the Famicom didn’t have. The NES also wasn’t the first designed console with encryption since the 7800 had it first. The 7800’s encryption was meant to prevent unauthorized adult games – like Mystique’s titles – from appearing on an Atari console with advanced graphics. And Nintendo wanted to prevent all unauthorized third party developers from releasing titles on the NES, period…supposedly in order to prevent another crash but it was all about their profit line and their adoption of JVC’s VHS licensing business model and applying it to consoles. If you ask any former Atari Games/Tengen engineers about the whole thing, they’ll tell you that they were almost finished with their reverse-engineering efforts but the company’s leadership and corporate counsel jumped the gun with their gaming of the US Patent Office with their alleged “fraud” in obtaining the code which ultimately botched their case and their third-party efforts on the NES.

It should be noted that Tengen was one of the first officially licensed third-party developers to support the Sega Genesis. They also patched up things temporarily with Atari Corp so the impressive Atari Games arcade library appeared almost in its entirety for the Atari Lynx system whereas it had been almost wholly absent from the Atari 7800 during its war with the NES and the SMS. The separate companies had another falling out during the Atari Jaguar’s development which is why the library’s titles didn’t start appearing until the Jag was nearing its ultimate discontinuation.

Flash-forward to today. The company using the “Atari” brand and IP today is really the remnants of Infogrames. And the Atari Games/Tengen IP is owned by “Midway” which is just a brand owned by WB Games, a division of Time Warner, which is now a division of AT&T. And to think there was that rumor floating around in the early 80s that Atari would buy AT&T…

As you said, Atari Games did reverse-engineer the chip. What you said above is right on: ‘If you ask any former Atari Games/Tengen engineers about the whole thing, they’ll tell you that they were almost finished with their reverse-engineering efforts, but the company’s leadership and corporate counsel jumped the gun with their gaming of the US Patent Office with their alleged “fraud” in obtaining the code, which ultimately botched their case and their third-party efforts on the NES.’

I worked in the clean room at Tengen with the hardware engineer who made the Rabbit and Rambo chips. We were reverse-engineering the SNES, looking for patent infringements.

As you said, Atari Games did reverse-engineer the chip. What you said above is right on: ‘If you ask any former Atari Games/Tengen engineers about the whole thing, they’ll tell you that they were almost finished with their reverse-engineering efforts, but the company’s leadership and corporate counsel jumped the gun with their gaming of the US Patent Office with their alleged “fraud” in obtaining the code, which ultimately botched their case and their third-party efforts on the NES.’

I worked in the clean room at Tengen with the hardware engineer who made the Rabbit and Rambo chips, we were reverse-engineering the SNES, looking for patent infringements.

Seems you are talking about the same time ATARI and NINTENDO were in talks of being in buisness together. Did they crack it or did they screw up the deal?

http://www.atari.io/atari-nintendo-nes-deal/