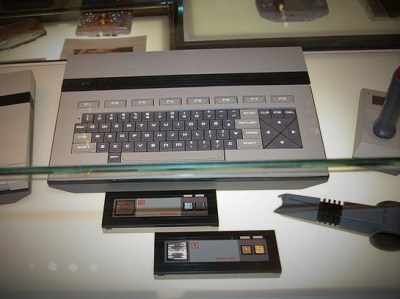

The story goes that Atari was developing a premium model of their popular home video game console, the Atari 2600, for the 1981 fiscal year. Internally known as the Stella RC, this model revision promised touch sensitive game selection toggles, LED indicators, and onboard storage for the controllers. The focus of the project, however, was the “RC” in Stella RC which stood for remote control. Atari engineers wanted to free players from the constraints of the wires that fettered them to their televisions.

Problem with the prototypes was that the RF transmitters in the controllers were powerful enough to send a signal over a 1000 ft. radius, and they interfered with a number of the remote garage door openers on the market. Not to mention that if there were another Stella RC console on the same channel in an apartment building, or simply across the street, you could be playing somebody else’s Pitfall run. The mounting tower of challenges to making a product that the FCC would stamp their approval on were too great. So Atari decided to abandon the pioneering Stella RC project. Physical proof of the first wireless game controllers would have been eliminated at that point if it were created by any other company… but prototypes mysteriously left the office in some peculiar ways.

“Atari had abandoned the project at the time…[an Atari engineer] thought it would be a great idea to give his girlfriend’s son a videogame system to play with…I can’t [comment] about the relationship itself or what happened after 1981, but that’s how this system left Atari…and why it still exists today.”

– Joe Cody, Atari2600.com

Atari did eventually get around to releasing some wireless RF 2600 joysticks that the FCC would approve. A couple years after abandoning the Stella RC project they released the Atari 2600 Remote Control Joysticks at a $69.95 MSRP (roughly $180 adjusted for inflation). The gigantic price tag mixed with the video game market “dropping off the cliff” in 1983 saw few ever getting to know the bliss of wire-free video game action. It was obvious that RF game controllers were simply ahead of their time, but there had to be cheaper alternatives on the horizon.

Out of Sight, Out of Control with IR Schemes

Video games were a dirty word in America in 1985. While games themselves were still happening on the microcomputer platforms, the home console business was virtually non-existent. Over in Japan, Nintendo was raking in money hand over fist selling video games on their Famicom console. They sought to replicate that success in North America by introducing a revised model of the Famicom, but it had to impress the tech journos that would be attending its reveal at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES).

The prototype system was called the Nintendo Advanced Video System (AVS). It would feature a keyboard, a cassette tape drive, and most importantly two wireless controllers. The controllers used infrared (IR) communication and the receiver was built-into the console deck itself. Each controller featured a square metallic directional pad and four action buttons that gave the impression of brushed aluminum. The advancement in video game controller technology was too good to be true though, because the entire system received a makeover before releasing as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) that Christmas. The NES lacked the keyboard, the tape drive, and the IR controllers and its change in materials hardly captured the high-end flash of the AVS. The removal of IR meant the device was cheaper to manufacture. A decision that ultimately helped the NES to become a breakout success that in turn brought back dedicated video game consoles single-handedly.

Third party manufacturers were also able to ride Nintendo’s success to bring out the wireless controllers that Nintendo wouldn’t. Chief among the third party wireless controller offerings was the Acclaim Remote Controller. Released in 1989, the Remote Controller featured an adjustable turbo switch and could be played up to 30 ft. away over IR. That was mostly true, as long as no one was standing in front of the receiver. Nintendo would revisit the idea of infrared controllers when they released the NES Satellite adapter. It was more of a wireless controller hub than controller itself, but up to four controllers could be plugged in for simultaneous gameplay in supported titles. It worked well enough as long as it was provided a regular diet of six C-cell batteries, but the line of sight requirement was limiting. Sadly infrared continued to be the extent of wireless controller technology for the next decade (including first party IR controllers releasing for the Sega Genesis and Sega Saturn), and would ultimately take a company that always ran parallel to gaming to provide a new path forward.

It’s Really More of a Spectrum as RF Came of Age

Life in the year 2000 was less futuristic than all the sci-fi depictions of it would have their readers believe. For all the promises of robotic servants and flying cars, the reality was that most things still needed to operate as they did in the 20th century. Intel sought to change that in some small way when they announced their Wireless Series of PC peripherals at CES that year. Obviously there was a wireless mouse and keyboard combo shown off, but curiously Intel also revealed a wireless game controller. Intel was always at the forefront of processor technology, but video games were more of a “happy accident” that helped to drive their main business.

All devices in the Wireless Series connected via the same USB receiver called, “the base station” over the 900 MHz band. A mixture of up to four devices could be connected simultaneously meaning that local multiplayer could finally work on PC and it wouldn’t require monopolizing every last bit of I/O. The setup sounded great, in theory, but there were a couple of issues with the Intel Wireless Series Gamepad’s design. To put it succinctly, it looked like a toilet seat.

The introduction of a UHF spectrum controller would be refined a few years later by Nintendo. A year after launching their GameCube console, Nintendo released the WaveBird controller in 2002. Many gamers saw it as revelatory. Being able to play a game on the other side of a wall, while impractical, was a freedom that few were able to experience previous to that controller’s release. Eager to bring parity to other platforms, third party manufacturers like Logitech would follow suit by releasing cordless controllers of their own. Though in an effort to increase battery life those controllers would integrate the 2.4 GHz band.

To this day wireless controllers still operate within the ISM band. From the Bluetooth connectivity of the Nintendo Wii remote to the proprietary protocol of the Xbox One Elite controller, wireless controllers would become the norm rather than the exception for home consoles. The convenience they provide is indispensable to the enjoyment of video games in their current form. Although the company that originally tinkered with wire-free gaming is no longer around, the result of that tinkering remains.

Wireless Is a Marketing Magnet

There is perhaps no better way to relive the evolution of wireless controllers than through the marketing campaigns that grew up around them. To that end, we close today with some of the ads that trumpeted this march of technology.

I still got GAME MATE 2 in it’s original packaging, rarely used. :)

I cut up an NES Satellite when I was in high school to switch it to using a wall-wart power supply, as it had quite an appetite for batteries. Unfortunately, I seem to have thrown the LEDs’ aim off as well, as it would intermittently lose the signal. Interestingly, this resulted in the system keeping the same inputs it had when the signal was lost, instead of having it report no controller input.

Yep – the Gamecube Wavebird was the first to really nail it.

“meaning that local multiplayer could finally work on PC”

False, two port game cards were out in the 80s, and you could split each port into two channels.

You could, but the splitter cable and second port didn’t come included with most PCs. That, and when the PC eventually got some worthwhile games (after VGA and the Soundblaster), PCs used joypads. Often with 4 buttons, using the 2 buttons assigned to each player. Sometimes with 8, taking over player 2’s joystick controls as well for the extra 4. So you could only have one player per port. And I don’t recall ever seeing a game that used Game Port 2, I’ve never physically seen the second port either.

Prior to that, the PC standard was weirdo analogue sticks for Flight Simulator II. Doubt anyone under 40 owned one of those.

It’s only USB that really, more or less, made multi-player games controllers work on PCs.

Even before that, I remember playing a game on the Apple ][ that allowed 8(?) players at once, everyone using their own 3(?) keys on the same keyboard. :grin:

“They sought to replicate that success in North America by introducing a revised model of the two year old Famicom”

Fixed that for you. They did it again with the SNES, repackaged the two year old Super Famicom for markets outside Japan.

Some might argue that the first year of the 21st century was 2001, not 2000.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Millennium#Debate_over_millennium_celebrations

They might, but even less people would be inclined to listen to them now.

Back in early 80s I stumbled over the General Instruments 256 command infrared transmitter receiver pair of ICs, useful for not only keyboard, but lots of other remote control applications. (AY-3-8470, AY-3-8475) Using a pair on each end I set up a 256 command remote control over a single sheiled pair Belden cable. (R-T-ground) Used initially just to switch data line from office between two different computer systems in lab. Could be switched from either end. Wish such chips were so readily available today.

Nowadays if you want something similar, it would be simple enough to program a small micro to act as a simple dedicated IR bridge so you can interface it as a module into another system.

Actually, there were probably nearly 2 dozen production samples made of the wireless Atari 2700. Some have gotten into the hands of collectors and former employees. I had a collector who found his in a thrift store photograph it for my book, Art of Atari. This was not a prototype, but a finished console.

What would be nice are replicas of the Atari 2700 sticks, of course with far less powerful transmitters. Put the receivers into DE9 dongles with a power jack on the end. Y the wall wart cable with two connectors so it can power two dongles.

Of course a few improvements would be nice, like dual fire buttons.

“Although the company that originally tinkered with wire-free gaming is no longer around,…”

Actually, yes they are, though I’ll give you that they don’t dabble in that arena any longer. Them and Sega now only makes software for other game systems.

https://www.atari.com/atari-games/