As we’ve seen time and time again, the word “hacker” takes on a different meaning depending on who you’re talking to. If you ask the type of person who reads this fine digital publication, they’ll probably tell you that a hacker is somebody who likes to learn how things work and who has a penchant for finding creative solutions to problems. But if you ask the average passerby on the street to describe a hacker, they might imagine somebody wearing a balaclava and pounding away at their laptop in a dimly lit abandoned warehouse. Thanks, Hollywood.

Naturally, we don’t prescribe to the idea of hackers being digital villains hell-bent on stealing your identity, but we’ll admit that there’s something of rift between what we call hacking versus what happens in the information security realm. If you see mention of Red Teams and Blue Teams on Hackaday, it’s more likely to be in reference to somebody emulating Pokemon on the ESP32 than anything to do with penetration testing. We’re not entirely sure where this fragmentation of the hacking community came from, but it’s definitely pervasive.

In an attempt bridge the gap, the recent WOPR Summit brought together talks and presentations from all sections of the larger hacking world. The goal of the event was to show that the different facets of the community have far more in common than they might realize, and featured a number of talks that truly blurred the lines. The oscilloscope toting crew learned a bit about the covert applications of their gadgets, and the high-level security minded individuals got a good look at how the silicon sausage gets made.

Two of these talks which should particularly resonate with the Hackaday crowd were Charles Sgrillo’s An Introduction to IoT Penetration Testing and Ham Hacks: Breaking into Software Defined Radio by Kelly Albrink. These two presentations dealt with the security implications of many of the technologies we see here at Hackaday on what seems like a daily basis: Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE), Software Defined Radio (SDR), home automation, embedded Linux firmware, etc. Unfortunately, the talks were not recorded for the inaugural WOPR Summit, but both presenters were kind of enough to provide their slides for reference.

Internet of Broken Things

As you might have guessed from the name, An Introduction to IoT Penetration Testing, had a fairly serious slant towards the practical exploitation of various Internet “things”. In this presentation, Charles described the operation of a number of extremely interesting software packages which have never before made an appearance here on Hackaday. That such incredible tools have managed to fly under our radar for so long is frankly evidence enough that we should be making a better effort to collaborate with our more security-minded peers.

For working with Bluetooth Low Energy, Charles suggests btlejack, a project which uses up to three BBC Micro:Bits flashed with a custom firmware to sniff, capture, hijack, and even jam communications. Running the tool with three devices connected to a USB hub allows it to cover more channels and increases the likelihood of it capturing what you’re looking for. If you’re not in a country that was literally handing out Micro:Bits, you can also use btlejack with Adafruit’s Bluefruit LE sniffer or a nRF51822 Eval Kit.

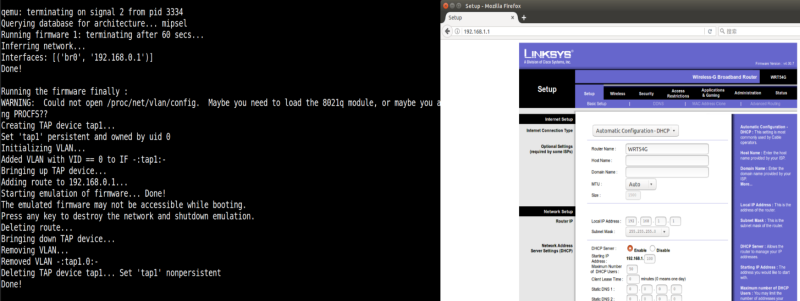

When poking around with embedded ARM or MIPS devices, Charles says he’s had great luck with Firmadyne, an emulator package which allows you to run firmware images. He demonstrated it using a firmware meant for the venerable Linksys WRT54G router, showing how the web interface of the “router” was now accessible via a virtual interface on the local machine. More importantly than being able to simply run the firmware, Firmadyne also allows you to plug in a debugger and explore the device’s virtual filesystem to extract vital clues on how it operates.

While talking about hypothetical situations can be fascinating, Charles also peppered his presentation with real-world examples pulled from over a decade of experience in the IT field. One which was particularly interesting was what he called the “IoT On-Boarding” attack. In this scenario, he demonstrated how he was able to leverage the unencrypted configuration interface of WiFi smart bulbs to collect the encryption keys for the network the user ultimately joins the bulbs to. We’ve recently seen that these bulbs have a tendency to store network credentials in plain-text internally, so the fact that their initial configuration interface doesn’t use encryption either sadly doesn’t come as a huge surprise.

Cheap SDR is a Huge Deal

A big part of Ham Hacks: Breaking into Software Defined Radio was based on an assertion that most Hackaday readers are likely familiar with: the RTL-SDR project was an absolute game changer. That’s not to say Kelly thinks a hacked TV dongle is necessarily your best option in 2019, but that it opened the floodgates for low-cost SDRs. Before the RTL-SDR project, the prices for SDRs were well outside of the casual hacker’s budget, effectively blocking a huge chunk of the community from exploring the RF spectrum. Now that anyone with $20 in their pocket can sniff from the low Megahertz all the way up into the Gigahertz frequencies used for satellite communications, systems which were previously “secure” simply because few people could listen in on them are now ripe for the picking.

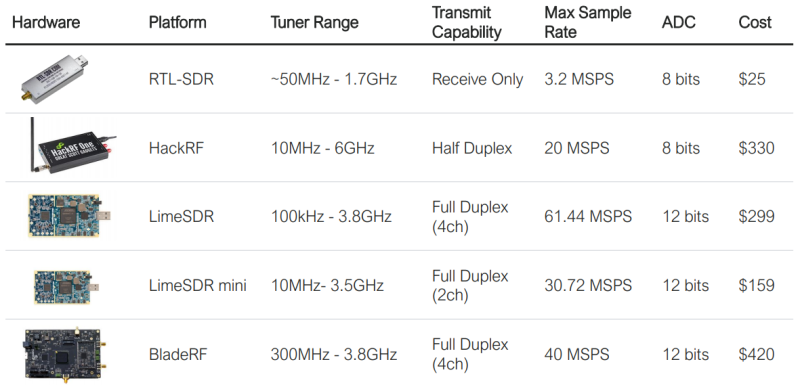

Kelly gave those in attendance a crash course in RF communications, and then went over some of the different SDRs on the market. She explained the practical considerations of things like tuner range and sample rate, and how the perspective radio hacker should factor those these variables into their purchase. But she also spoke on the importance of community and documentation; the LimeSDR Mini is an incredible deal for the price, but it doesn’t have as large a community as something like the more expensive HackRF.

With the wide world of SDR hardware out of the way, Kelly went on to giving some practical demonstrations of capturing signals and ultimately converting that into data bits which can be examined. The first half of the process: identifying which frequency the target device uses, fine-tuning with an tool such as GQRX, and then capturing with the rtl_sdr command is something we’ve seen used in a number of projects already.

But the last piece of the puzzle, taking that capture and getting usable data out of it, is something we haven’t seen nearly as much of. Kelly went over tools such as Inspectrum, DspectrumGUI, and of course Universal Radio Hacker, and demonstrated how they are used against an SDR capture file. Many of the SDR hacks that come our way essentially just re-transmit the original capture with little consideration of what information the signal actually contains, and it was interesting to see a more in-depth look at how these open source tools can help move from simple mimicry to comprehension. Once you’re able to decode the data being sent over the air, you’re well on the way to being able to modify the data; and that’s where the real fun begins.

Through the Looking Glass

These presentations dealt with subjects which are familiar to Hackaday readers, but in both cases, brought something new to the table. Seeing “the other side” of technology was a central theme of the WOPR Summit, and these talks demonstrate that the perspective shift can often bring new details to light. Some mad lad clustering together BBC Micro:Bits to capture BLE traffic is about as far up our alley as you can get before busting through the front door, and the fact that we haven’t seen it until now is a perfect example that information isn’t moving as smoothly between the different camps as it should.

Hopefully other hacker events will adopt this more eclectic approach to presentation topics in the future, and help establish a better dialog between the cornucopia of hackers that are out there. Otherwise we run the risk of not only missing out on useful techniques and tools, but worse, reinventing the wheel when a solution has already been developed.

So, what’s that thing sticking up between the pig’s hind legs in the opening slide?

A microphone by the looks of it :)

“Thanks, Hollywood.”?

Hmmm… for some reason I always seen myself as an inventor, a tinkerer but never a hacker, because even before Hollywood began confirming the “hacker” image where hackers were hackers and people playing with electronics were not hackers (they were called electronic hobbyists), people making things from wood were not hackers (they were called craftsmen), people making from things from metal were not hackers (they were craftsmen as well, just with a different craft), etc. People in the 80’s, cracking copy protection from games, were called “crackers” and operated in “crackergroups”, a real hacker was almost never seen and there was no reason for them to show themselves and what they did was mostly not understood by the general public.

But these days many people are jack-of-all-trades as they play around in every field a little bit, but are none of the above. Then for some reason it catches on to call these nice people hackers. And for the kind people that they are (actually they didn’t care) somebody called them hackers and got away with it. Which is strange, as most of them are lacking sufficient programming or computerskills to perform any real hacking. This went on for a while and now it seemed to be an established term in the “makerscene” to call yourself a hacker if you make something technically interesting or using parts not intended for that purpose.

And now suddenly, Hollywood get’s the blame? That doesn’t seem fair to me, someone mistakenly called the wrong group of people by the wrong name, others unknowingly (or willingly because the thought the sound of it was interesting) copied it. And now the confusion is complete. But, please do not blame Hollywood as that isn’t fair as for some reason, I really believe they’ve got a lot of things right. If you look at the documentary “War games” from 1983 with Matthew B. I think they got a nice portrait of such a person. Alhtough I always had my doubts of the gear used, as it must have cost a fortune back then and where did this kid pay that from?

Exactly. I understand people want to re-appropriate the term ‘hacker’ and make it nice and positive. But it’s just not as useful of a word with that definition. A tinkerer is a tinkerer. Tech workers and devs everywhere would love to have you believe that the word “hacker” means “any computer-toucher who even partially does their job.” They act like they’re doing the world a service by reclaiming this word, but really they want the image and coolness of the old connotation to be applied to themselves without actually having to live on the criminal fringes of society or do anything more risky than work a day job in the bay area. Come on. That’s lame. The black hats deserve the term more than we do.

It’s been used to refer to black hat a lot longer than hollywood and stock image websites have been harping on it, too. To imply that some kind of media conspiracy corrupted the word is kind of disingenuous. It means what it means through the organic evolution of language, and you aren’t ever going to pry it back from that. And that’s fine. The dilute, all-encompassing use of the word hacker is fucking useless anyway. Is a prehistoric human chipping at flint a hacker? Is a baker a hacker? Is any human who manipulates information or matter in any way a hacker? Then everybody is a hacker, and that means nobody is. So the word is pointless. Just let it refer to the black hats and stop trying to make yourselves sound cool because you have a job in software or engineering and that sounds boring as hell. Sorry, them’s the breaks.

It was at M.I.T. that “hack” first came to mean fussing with machines. The minutes of an April, 1955, meeting of the Tech Model Railroad Club state that “Mr. Eccles requests that anyone working or hacking on the electrical system turn the power off to avoid fuse blowing.” The lexicographer Jesse Sheidlower, the president of the American Dialect Society, who has been tracking the recent iterations of “hack” and “hacker” for years, told me that the earliest examples share a relatively benign sense of “working on” a tech problem in a different, presumably more creative way than what’s outlined in an instruction manual.

Lifted from:

https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/a-short-history-of-hack

*ascribe

*subscribe

WOPR? My only thought is “is takes two hands to handle a WOPR”. I wonder what it is and what it stands for, I guess I should go look it up.

The hacker thing is a lost cause. Nobody is going to use “cracker” as keeps getting proposed. 99 percent of the world thinks that hacker is the dude writing the malware that has their computer all screwed up, and nothing is going to change them. We are a tiny subset of people who have chosen to use the work in a different sense, what might have been called an inventor or tinkerer or something positive, or at least benign. But we are a shrinking minority with a small voice We need to be realistic and understand that if we tell most people we are a “hacker”, they are going to think of us as a shoplifter, child molester or something of the sort. Who used the word in what sense first is irrelevant at this point.

Read this article from last week to learn more about WOPR.

https://hackaday.com/2019/03/21/first-wopr-summit-finds-the-winning-move/

Cracker is also a racist term, so it won’t work well.

It used to mean “whip cracker”, for the ranchers that made a living in Florida before it became a tourist trap.

At first I thought you meant “whippet cracker,” which is also quite popular in Florida I imagine.